-

iPad의 멀티 윈도우 소개

멀티태스킹을 지원하면 iPad 앱의 성능을 근사하게 개선할 수 있습니다. 간편하게 앱에서 두 인터페이스 인스턴스를 나란히 실행하도록 설정할 수 있습니다. 앱의 고객에게도 유용한 기능이 될 것입니다. 드래그 앤 드롭과 같은 기존 기능을 사용하여 세컨드 윈도우를 쉽게 만드는 방법을 배우고 여러 윈도우를 지원할 때 앱 라이프 사이클이 어떻게 달라지고 모든 응용 프로그램에 어떤 영향을 미치는지 알아보세요. 몇 가지 일반적인 실수와 이를 해결하는 방법을 익히면 개발자와 고객 모두 환상적인 경험을 누릴 수 있습니다.

리소스

관련 비디오

WWDC21

WWDC19

-

비디오 검색…

Thank you.

Good afternoon. My name is Ken Ferry from iOS System UI, or Springboard if you know that name. And today, myself, and Steve Holt, and James Savage are going to talk to you about multiple windows on iPad.

So what are we talking about? Well, on iOS 12 and before, if you swipe up in the switcher, you got this nice little grid, you can tap on things, gets you to applications, it's great.

On iOS 13, it looks pretty much the same, but those are no longer applications. Those are Windows, or as you'll see it's called the in API scenes.

So that's what we're going to talk about today. We're going to talk about what does this mean for your app. And it's an introductory talk so we're going to do it really from top to bottom. We're going to start out with design issues. So, just what are you going to want to be thinking about doing at all in your app for multiple windows? We'll go on from there to the how of multiple windows, starting out with application lifecycle, which is the biggest change to the application programming model. That's like foreground, background and active.

Go on from there to drag and drop, which is how you mostly make windows. And then, James will walk you through next steps of further adoption that you might want or need to do in your app in order to be a good multiple window app. So let's get started. We're going to talk about these design issues. And, first, we just want to talk about what these windows or again scenes are.

It is -- there's really kind of two questions we want to try to answer here, is first, does it make sense for my application to support windows at all, multiple windows? And then, if it does, what would those windows be? Like how do they act, what are they, you know, how does the user think of them? We'll answer those questions by looking at examples from Apple's own apps and generalizing to how it might apply to yours. So that's what you're going to be thinking about.

So we'll start out with Safari. Safari is a poster child for this kind of multitasking, that it was kind of already there. This is actually a screenshot from iOS 12 where Safari already supported the split-screen view.

In iOS 13, it looks like this, or iPadOS, it looks like this, which is not really that different. That's because it was just so important that we did it in Safari even before we could -- we brought it to a whole rest of the operating system. For generalization purposes, though, what is it that we want to be thinking about here? The first thing to be realizing is that every -- there's only one kind of window in Safari. They're all the same as each other. They're just kind of clones of the interface. And each one can do everything in the application.

That's important because for -- on the iPad, the user should be able to do everything from just one window if they want to. They should be able to create more windows f they think that's useful. But if your application requires multiple windows to you -- to work, then something has gone wrong.

So, it's not important that it always be quite like this where they're all just clones of each other, but it is important that the first window that the user create be able to do everything. Now, that said, in this case, they are all the same. And you'll actually see that in most of Apple's apps, that's what we've done. So, and that's -- so that's not a bad thing. That's the easiest thing for you to do and it very well might be the right thing. We'll look at the examples. Though before I go on, I just want to note that like because we did adopt, you know, the system-wide support for this, it did get better in Safari. Now, you can like tear off one of these things and throw it off to the side and concentrate on something else for a little while. You know, it's fancy.

Going on, document-based apps.

Here, we're looking at pages. And in any document-based app really, the user would have the expectation that they're able to view documents in different windows at the same time. So you're definitely going to want to support that. But there's something you might or might not be a little bit surprised by here. If you look at the top left, there's a button there that says documents on both of those windows.

Each of these windows is actually a full browser. You can go back from the document you're looking at and look at a different one. So it's actually the same case as Safari. There's only one kind of window and pages.

That's not necessarily going to be the case in every document, not even necessarily in every document-based app I think. But in here, it does make sense. And we'll look at cases where it doesn't going on. Maps also is -- there's only one kind of window. But the reason I still want to -- we still want to talk about it is because it illustrates something to that other point of should my application even support multiple windows. That's because at first, this didn't necessarily seem like that attractive of a case because it seems like you just, you know, you open maps, you go somewhere and then you close it. And that's how it works. That's actually not the case. If you're planning an evening here, you might be going to dinner and then after dinner, you're going to a show. It's really useful to be able to do each of those two legs in a different window. So you can think about them or change them without losing all your state in between.

And that seems specific to maps, but the reason to bring that up is that we've pretty much always found that. So, for all the cases where we weren't sure if multiple windows would be useful or not, we pretty much came around to that it is. So, I'll go through more examples of cases where it is, but be thinking about that when you're when you're doing yours.

Oh, and, you know, because it is using the system multi-window, that does mean that once you want to focus on one of them, say where I'm going to dinner, you know, I can rearrange my spaces and pull out notes and do things that you otherwise wouldn't be able to do if it was just inside of one application.

So, Mail is the first case where there are different kinds of windows that we've looked at.

Craig showed this in the keynote, but when you reply to a message, that brings up this modal interface same as it always has, but you can tear it off.

And then you might even want to use your slide over stack as almost like a to-do list of actions that you are pended and still need to perform.

So in this case, if you look at the window again, look at the top. There's a Send button, that's the blue arrow, and there's a Cancel button. But there's no way to get back from here to see the rest of your mailboxes or anything like that. These windows are dedicated. And then, when you and -- so when you hit one of those buttons, it will close the window. So I think Craig showed sending in the keynote, so I'm just going to show dismissing. If you first click to get out of the slide overview to just view one of them and then click Cancel, it looks like that. And all those animations are available in your app too. They're talked about in some of the later talks.

Messages also has different kinds of windows, but it's not just like a to-do list. It's not just like a transaction or an action like in the other case. Here, when you pull off a thread into its own window, that's just a dedicated window that pertain -- that is only for that one thread. And you can see it as a Done button at the top from when you're finished with it.

That's more of an organizational tool, but it's a very handy organizational tool. And then going back for a minute to that question of should my applications support multiple windows, here in Messages, using this, I found it incredibly useful to be able to look at one conversation and scroll up and find some information and reference it while I talk to someone in the other window. And I can tell them, and if they have more questions, I don't have to somehow go back and forth. I've still got it there. So, in general, I think the generalizable principle there is being able to refer to something, being able to see one thing while you're acting in a different window.

The last example of an Apple app I want to talk about today is Calendar.

What's interesting here is that Calendar supported drag and drop for events already. But by adopting multi-window, now, if you view say two different weeks at the same time in Calendar, you can drag and drop from one of those weeks to the other.

And that didn't require any additional changes in Calendar to support that. That's just the drag and drop they already had. So if your app supports drag and drop by supporting multiple windows, also you can kind of magnify the power of both of those features working together. So, yeah. And so like I said, pretty much what we found when we looked at this is that any app of sort of reasonable robustness pretty much benefits from it. So, you know, I can't completely answer the question for your apps. You'll have to think about it. But hopefully some of these examples will help you think of those cases where it would be useful for your users. Last thing I wanted to note here before we go on to the next topic is, you know, we talked about iPad apps on the Mac this year. And Mac apps have windows and without all this API, you couldn't make new ones, so it's going to be kind of a weird Mac app. But now you can. So do that.

Alright. So that's everything about what are these windows at all. But now, still from a design perspective, what interactions do you want to enable in your app so that the user can create new windows? We're going to explore that by first showing what the system can do for you for free, and then extrapolating to what users would expect to be able to do based on what is already there.

So for starters, Craig showed App Expose already. And in App Expose, there's always this little button in the top right, and that that little button is make new window. So that's something that's completely for free. If your app supports multi-window, that will make new windows. There's only one other thing that we can really do for all applications, but this is the one that kind of becomes the foundation for everything.

If you're already looking at your application and you grab the application icon and drag it over to the edge, that seems like it's really explicitly saying, I want to make another window right here. Just what else could that mean? And we have all the contexts that we need to make that work, so it does. But given that, now if the user picks up something else, say a tab in Safari and they do that drag, they're also going to expect that to work, and that the system can't just do it for you. It's not a lot of work to adopt the API to do that, but you do have to actually adopt something to make that work. And that really extrapolate -- that extends to all drag and drop. Pretty much if the user can pick something up and it makes any kind of sense for that to result in a new window, they're going to expect that it can. And you should enable that. A really common case for that is any kind of master detail view. So here in message -- in Mail, you know, there's this left-hand table view that represents -- each cell represents a message. And if you tap on the cell, then you see the whole thing, right? So the user is going to expect that if you drag out of the table view that that's going to pull out a window for a message.

OK. So mostly drag and drop. You can also create windows through explicit action.

So in an application like Safari or really anything that has links at all, you might want to support that if you press and hold on a link that that might pull up a popover and the popover might have a button that says Open in New Window. And that is the case in Safari. You can do that. And that's how it reads, it says Open in New Window.

So that pretty much implies that there must be -- we are, there is an API in UIKit that just whenever you call it, it will open a new window.

So, you could do a lot with that, you know. You could set up like a voice recognition thing so that like whenever I sneeze, it like creates like a new sneeze window like for analyzing my sneeze like kind of like Shazam or something like that. But -- you could do that, but it would be weird. So you shouldn't. The -- though it actually sounds kind of fun, but you know. As we were saying before, the user should not be forced into using multiple windows. That should always be an action they take for themselves. So it always needs to be something that they recognize as very explicitly creating a new window like this Open in New Window. So -- but that's just -- that's design level. So that's something you have to do for yourselves in your own applications.

Anyway, that is everything we have to say about design and the what. So to talk about how you can go adopting this, I'm going to turn it over to Steve Holt.

Thank you. Thank you, Ken. My name is Steve Holt and I'm an engineer in the UIKit Team. And hopefully, you've seen some great examples of how to adopt this new feature in your applications. And you're probably wondering, how do you actually adopt it in your applications? That's great because we're going to talk about that right now. So there are two classes you need to know about in general to work with this new feature on iOS and iPadOS, which is UIWindowScene and SceneSession. You might be familiar with how UIs in UIKit are structured today. You have a screen, you have all window or maybe multiple windows depending on your application. And then you have your views contained inside that window alongside your view controllers.

UIWindowScene inserts itself right in between the screen and your windows.

This lets you contain your windows to a single instance of user interface without forcing you to change your application or user interface structure too much from what you already should have today. So basically, a scene, it contains your user interface, and the system will create an on demand for you.

Whenever the user performs a drag and drop interaction, requests a new window opened up through your own interfaces or however that's achieved, the system will ask you to put UI onto the screen.

And then, if that scene should go background and it's not being interacted with anymore, the system can decide that it's just kind of hanging out there, we don't need it anymore, and we may destroy that scene.

So, if we're going to take that scene away, but clearly the user thinks something is there. I mean your application is still in the switcher right where it was before.

You need a way to understand what is actually in the switcher without having to rely on the actual concrete interfaces being suspended out of your application. And that's where SceneSession comes in.

The SceneSession represents the persisted interface state that the user of your applications were doing last. Now, they have a defined system role. This could be a standard application interface that you interact with on the display of the actual device, or could be for an external display. And every time a new window gets created on the system, your application is informed through the application delegate that a new session has been made.

And every time one has been destroyed by the user, either through interactions with our APIs, or because they swiped up in the switcher and destroyed that space, you get informed that that session has been destroyed.

And your UI scenes from the previous slide connect and disconnect from these sessions over the lifetime of your application.

Now, this has some interesting effects with your application lifecycle as you might expect.

To represent that, there is a handy chart we made up. We have three sessions in our application, which represents three different spaces in the system that my application is showing its interface.

And right now, they're disconnected. They're below that background line. So, my application just reports that its application state is background. Now, if I should activate one of the spaces that my session is on, the application state will go up and go all the way up to foreground active along with that connected scene.

When I send that scene back to the background, the application state descends down with that scene.

If I were to switch to any of the other two sessions, then my application state would remain at the foreground active state to represent the fact that the overall state of the application hasn't changed.

When it comes to your application class and your application delegate class, we used to put the combination of the interface with the rest of the system, and the lifecycle in that ApplicationDelegate and Application object. This doesn't really work too well anymore.

So, we split it up. We have your application which still represents the state of the system as a system process, and the ApplicationDelegate which gets events and delegate notifications about processes, things, and launching and terminating the app as a process. But now your scene actually encapsulates the UI state and full. Any questions you have about the status bar, you ask those to the scene now.

And your SceneDelegate gets informed about opening up URLs in a particular context, returning from the background, going to foreground, et cetera. And of course, you have SceneSession which represents that persisted UI state.

Now, you might think that this is a lot of complicated API.

So, if you have code like this in your application right now, you're going have to make a really big change and move your implementation of these methods into these methods.

For the most part, we've kept it as similar as we could. Application didn't finish launching, becomes willConnectTo session.

EnterForeground is enter foreground. It's just on the scene now instead of the application, and so on.

Now, there is a hitch here with state restoration. It's going to be really important. So, your users can look at the state of the switcher, go to a particular space, and then have their information come back exactly as they left it.

So to help you with that, we've borrowed a little bit of API from the Handoff.

And we represent stateRestoration as an NSUserActivity now.

You can put whatever information you wanted.

And at various points in the lifecycle, you like, it will request that user activity from the SceneDelegate. And then, when you're seeing restores, will pass it right back in as the connection delegate callback. And should no scene actually exist for that particular session, you can access the stateRestorationActivity directly on the session so that should you do a background fetch and need to update a particular one, you can go and find which one you'd change data for. So, I'm going to give you a quick demo to show you what it's like to adopt this new API in your application.

So, I have an application here and it was authored by a good friend of mine and colleague on my team, John Ham. And he wrote what is, to me, one of my favorite apps ever. You'll see it in just a second when the simulator comes up, but it's fantastic. What you'll see when this boots is a fantastic gallery app that exercises all of collection view flow layout.

But it's going to show a really important point. It's a nice charming application. And we're going to go from having just a single instance of it and bring multiple windows.

Because when I use this application, I really want to be able to see more than one photo at a time. So we're just going to wait a little bit more for the simulator to boot up here. And here we go. We can launch apps.

As you can see, it is a marvelous application. And I can step in and view any of these photos and pop back out. Now, I can bring it up, and if I try to go into App Expose, I can't right here. And that's because this application doesn't have multi-window.

So, the first step to implementing this is to go into Xcode. Right here in the General tab, we have this nice new checkbox labeled Supports multiple windows. You can take a guess what happens when I check this.

We make a little edit in our info.plist, and if we jump to it, we can see that we have this new entry here called the Application Scene Manifest. This tells the system that the application supports the new lifecycle interfaces, and we can declare statically what interfaces for which type of roles we want to use.

Now in this case, I've prebaked a info.plist entry for you. So we're going to get rid of that. And now we have this right here. So, we've made this and this has already moved over our existing storyboard. And we've had a very, very basic SceneDelegate class that we have right here. And all this does is declare just a window, a really, really basic template class. We build and run.

And we're right back where we started, which is good. But now -- So if I could access the icon in the dock, I will be able to drag it up and move it over to the side of the iPad interface and create a new window, which is what that info.plist allows us to do.

But unfortunately, if I were to go back to the home screen, let the application terminate, and then launch it again, we don't quite get the same level of state restoration we did do before as you can see right here.

So to get that back, we need to implement a few things, which is OK. Now, like I said, to implement stateRestoration here, we need to take our existing stateRestorationActivity that we have. Windows return it from the new stateRestorationActivity for scene, delegate call. And way deep in the implementation here, we've been setting it on the application instance, which is not really what we want anymore.

We want to set it on to local windows scene like so. And then clear it out where we cleared it out before.

So now, we're returning our user activity so we can do stateRestoration.

Let's try it.

So what you'll notice here is that we're not quite done implementing the stateRestoration just yet. We need to do one more thing when our scene connects.

When the scene connects to the SceneSession, we get options and we get the session reference. Now, in this template that I pulled out, we're already looking for any user activities that we have gotten through Handoff or any other system facilities that vend us user activities. We want to prefer those user activities because that's what the user actually did.

But the stateRestorationActivity is special and it's on the session. So if you don't have one of those activities, we want to use our stateRestorationActivity.

So now, when we build and run, we restore back when the application is relaunched.

So that's how you adopt multiple windows in your application. It's pretty straightforward. You can use most of your existing application delegate logic and just move it to the scene, and it will run there.

Now, as Ken mentioned, the preferred way of interfacing with these drag and drop items is with drag and drop. And there are a couple of ways we can achieve this if you use existing universal links or references to file URLs that your application declares its own in info.plist, those will just work. But if you want to do something more custom, once again, you can use NSUserActivity. You can include that in your existing DragItem's NSItemProvider as a different object representation.

When you drag it off to the rest of the system, you'll get hit targets and drop points at system defined locations just like any other app icon drag.

And now to talk about the next steps is my colleague James.

Thank you.

Thanks, Steve. So to wrap up this talk, I have just three more things to talk about. The first is going to be a deeper look at the UISceneSession API.

Next, we're going to cover some case studies about common issues that we think you might see when you start duplicating your application's interface.

And lastly, I just want to talk briefly about some of the deprecations that we've added to UI application to support this new lifecycle. So let's get started by going over what a scene session is.

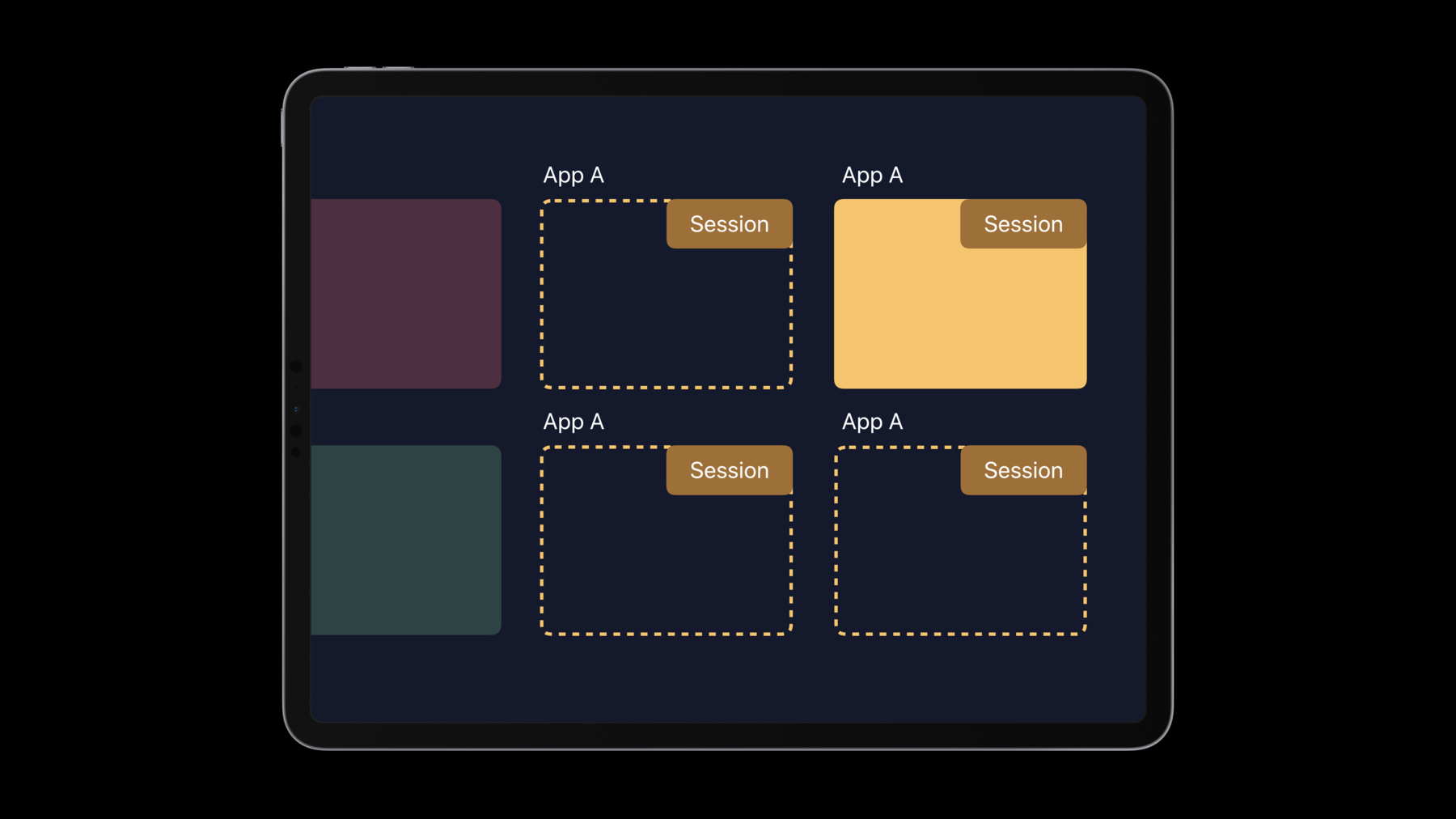

Going back to this diagram from earlier, you can see in the App Switcher, we have four windows of our application. And that is how the user will think about this, as four windows. But I want to encourage you as developers to think about these as scenes and scene sessions. And that distinction is important because while the windows that the user sees in the App Switchers will always be there as snapshots, the scenes themselves may not be loaded in your application.

They can come and go as needed, but the sessions will always be available to you. And because of this, we use the session for programmatic control over the windows. So I think these are some of the most exciting API that we're adding to multitasking this year because they allow you to create new windows programmatically, update the snapshots in the App Switcher, and close them on response to things like a user gesture, or if the document that they represent has expired in some way. So to go over when and how you would use these, let's look at some sample code. The first of these is the requestSceneSessionActivation API.

And what this lets you do is bring forward either an existing or a new scene of your application.

In this example, I'm trying to open a document. And I first check if the document has an existing scene somewhere in my application. And if it does, I pass it to this API and it will be brought forward. But if this document isn't open yet, I can create an NSUserActivity that references the context I need to open it later and pass nil to create a new scene.

Next is the requestSceneSessionRefresh API. You'd want to use this in the context where you may be received a push notification about a new message or in an app like Calendar when an event has changed. When you call this method, UIKit will schedule an update at some point in the future where it will connect your scene in the background. You'll have a chance to update the UI, a new snapshot will be taken, and then that will be saved into the App Switcher for later. You can also use this to update the stateRestoration user activity that Steve talked about. Lastly, is the requestSceneSessionDestruction API, which you can use to close a scene.

What's really cool about this is that it also comes with the scene -- this options object that lets you pick a semantic animation for how the scene should be closed.

You can see this in Mail with the Compose window. When the user sends a message, the sheet animates up off screen. And if the user saves it as a draft, it'll slide down to remind them that it's been saved for later.

You can use these same animations with your scenes and your apps. Now, window management isn't all that the session can do. We've also added state restoration to it, as shown with the NSUserActivity for stateRestoration.

We think for lots of apps, this is going to be a really simple and easy way to start saving your state, especially if you've already invested in technologies like Handoff.

But we also realize that many of you have apps with existing state restoration logic and maybe you don't want to work to integrate it with NSUserActivity. And for that, we have a persistentIdentifier property. Now, all this is is a string that is generated by the system. You can feel free to write it down into any databases or any files in your apps container that you use for state restoration. And it will be the same identifier for the same scene every time your app is launched, even across backups and restores of devices.

Lastly, there's a userInfo dictionary, which is great for storing small amounts of data, such as per scene customizations. You might use this for something like whether a sidebar is being shown, or the last used color at an ink picker. Really a great way to find things to put in this might be to go over data that you're already storing in your user defaults, because some of those things you might not actually want to be global to your whole app.

So, that's the new API for UISceneSession. But next I want to talk about what your next step should be after you built and ran your app with Xcode supporting multiple scenes. And that's of course debugging it.

Now, there's lots of code in your app that is very custom, and we've done our best to make the framework help you along the way.

But we can't really predict if there's any changes you'll need to make or what they might be.

But we think that there probably are. And we do want you to think about the code that you've written in the past. Adopting this new lifecycle and especially adopting multiple scenes might have changed assumptions that you made about how your application functioned.

There's no longer just one interface, and there might no longer be just one instance of a view controller. Of course, if you have automated test, that's great.

Those tests might continue to pass though, even when your users might see real bugs. And that's again because of these changes to the assumptions that you might have made. So the best way that you can find these problems before your customers do is just to play with your app, play with it, you're having two copies of it out at once. And it's a really great way to very quickly see when something doesn't quite line up like you meant it to.

Now, I've prepared a couple of case studies to highlight prototypical bugs that you might see.

But there's this common theme to both of them, and the theme is state, specifically, shared state.

Now, I'm willing to bet that almost all of you have used one of these classes in an application before because they're really common and really useful Cocoa classes. And they're also really convenient because of that singleton property. You can go be in a model object deep in your app and reach up to the UI device singleton and read off some configuration about what kind of device you're running on, and that's really powerful.

But this pattern also can have problems. Because of that loose coupling between layers and data, you can kind of lose track of where data is flowing in your application, who is reading it and how. But like I said, these are very, very powerful patterns because they're so convenient. And in fact, I expect most of you have written your own singletons at some point.

You might be using something that isn't quite a singleton like a global variable, or maybe you're piggybacking on an existing singleton in the kit.

Or maybe you're using the file system, which is itself just one big vault of data that's shared by your app. Now, I'm not here to tell you that you need to get rid of all your singletons or that shared state is bad, but I do want to encourage you to think about how you're sharing it, and whether you should be sharing that. There's lots of other advantages to factoring your data out, such as an easier time with unit tests.

So let's get into those case studies. The first one rolls around a state restoration.

And to work on it, I came up with this sample app before the talk. Now, it's just a nice little sketch pad editor. You can type some texts into it, you quit and relaunch it, and you see it again. And I follow the steps from the demo and I enabled support from multiple screens, and it's looking pretty good.

But when I quit and relaunch the app, this happens. I now I have the same content in both sides of my application and that's not really what I wanted. So I took a look at my database and the problem was pretty straightforward really. I was saving out this text file as a file in my apps container, but I was only saving it to one location. So every time either side of my application saved data, it overwrite whatever the other one had saved.

Now, there's nothing that you UIKit can really do for free here because this is code in my app. So I had to go and do two things. I had to correlate that persistent identifier for the scene session with the note for the right scene. And then I had to update my logic so that I could save multiple files instead of just one.

Now if you're going this route and doing manual state restoration, there's just one more thing I want you to think about and that's cleaning up the data.

When UIKit manages that NSUserActivity for you, it will take care of where to write it in once you remove it for you. But if you're receiving other large files tied to the lifetime of a scene in your app, then you'll want to clean them up using the new UI application diDiscardSceneSessions API.

This gets called with a set of sceneSessions.

And it's a great time to remove any data that really doesn't need to exist anymore.

And a document-based app like pages, you wouldn't want to delete the document. That stays in the file system. But configuration or preferences aren't needed anymore.

This method will be called immediately when the user swipes up on -- in scene of your app in the App Switcher if your application is running. Otherwise, you might receive a set of multiple sessions sometime after your next launch.

For our next case study, I want to look at UserDefaults, which is another really common and super useful class for applications.

UserDefaults are great for storing settings. And that's exactly what I'm using them for here.

I have this toggle for a word count bar in my app. And when I switch it on, a word count bar appears at the bottom of the screen. But unfortunately, it only appeared on the screen where I had the settings view controller is showing. It didn't appear in both windows and that's not what I wanted. I want this to be an application global preference. And when I looked at why this was happening, it was again pretty straightforward. I had a settings view controller and a settings view controller delegate.

Whenever the setting changed, I told the delegate, which was the text editor view controller behind, which then updated its UI. That's a very self-contained process. And at no point is the second scene in my application ever informed that anything is updated.

There's a couple of ways that we can solve this, but a really elegant way is using key value observing.

And I can do this in two steps. The first is to define a property on UserDefaults via an extension. This will give me a key path that I can use for key value observing. Here, I have my isInfoButton -- or, sorry, isInforBarHidden Boolean property, and I implement it in terms of the existing get and set methods on UserDefaults.

Next, I go over to my view controller where I register an observation on the standard UserDefaults. It takes that key path that I just defined in my extension and the change handler which encapsulates for the work that I want done anytime that value changes.

Importantly, I've also passed the option initial to this registration. What this does is really cool. It calls my change handler once for free when I set it up, which means that I don't have to have this code duplicated anywhere else. I don't have to remember to call one method when my view is loaded and another when I receive this update. There's just one source of truth for whether or not that's being shown right now. It's a really great way to make sure that your app's interface is consistent.

Now, everything looks great.

So we hope that those give you some ideas about things to look for in your applications.

If your application is already using best practices, you might already be doing some of these and have nothing to change.

But speaking of best practices, I want to talk about these new deprecations on UIApplication. As Steve mentioned, we've split out the responsibilities for user interface state and process lifecycle from the UIApplicationDelegate. And to go along with that we've also split them out of UIApplication. Now that you can have multiple scenes of your application visible at the same time, you could have a one with a light status bar content and one with a dark status bar content. And it doesn't make sense for us to be able to return just one value to you for this. So because of that, we are deprecating these properties on UIApplication and giving you new ones on the window scene.

We encourage you to adopt these new properties even if you're not planning to adopt support for multiple windows this year because it will put you in a great place if you consider doing it later.

We've covered a lot today. So I just want to go over a brief summary.

Earlier, Ken helped you envision your applications using many of the new powerful features that we've added to multitasking this year.

We think that users are really going to come to expect these out of apps because they're so useful and convenient. So we really want to encourage you to adopt them. We've made this API easy to adapt for existing applications. And we're also pushing it as the best practice for new applications. In fact, this is going to be the default template for new Xcode projects using this UI scene lifecycle. I also want to encourage you, because while there might be some issues when you adopt these new lifecycle changes, they usually have fairly simple solutions, including just the best practices that we've talked about in previous WWDCs. And lastly, I want to encourage you to move off of the deprecated UIApplication properties and onto UIWindowScene. These are available to you anytime you're running on iOS 13 or iPadOS, and you don't need to adopt multiple windows to take advantage of them. We have a couple more talks later in the week about advanced topics in multitasking, and also some labs this week, including ones focused specifically on multitasking on Thursday. I want to thank everyone for coming out today and hope you have a great week.

[ Applause ]

-