-

Swift Playgrounds 3

Introducing Swift Playgrounds 3: the latest iteration of the revolutionary app for iPad that makes coding in Swift interactive and fun. Discover how you can use your own playgrounds to rapidly iterate on code that uses device features. Find out how the new modules feature both helps organize your own code and provides new opportunities for playground book authors.

리소스

-

비디오 검색…

Hello, everyone, and welcome to our session on Swift Playgrounds 3.

My name is Grace Kendall. My name Joy Forbes. And my name is Jonathan Penn. We're all engineers working on Swift Playgrounds and we are so excited to talk about the new features that you can use to build ideas right on iPad with Swift. And we'll demonstrate some techniques that you can use to build even more engaging Playground experiences.

Swift Playgrounds is an app that you can write Swift code in as well as learn from content that other authors have made.

The code that you write is real Swift and it's compiled and run all on the iPad by the app.

Playgrounds you've created or downloaded show up in your list of documents as shown here.

And the more Playground section at the bottom shows other Playgrounds that are similar to the content you already have. If you tap the See All button, you'll see all the content available for download from Apple and the other feeds that you're subscribed to. You can also browse featured subscriptions in the From Other Publishers section at the bottom.

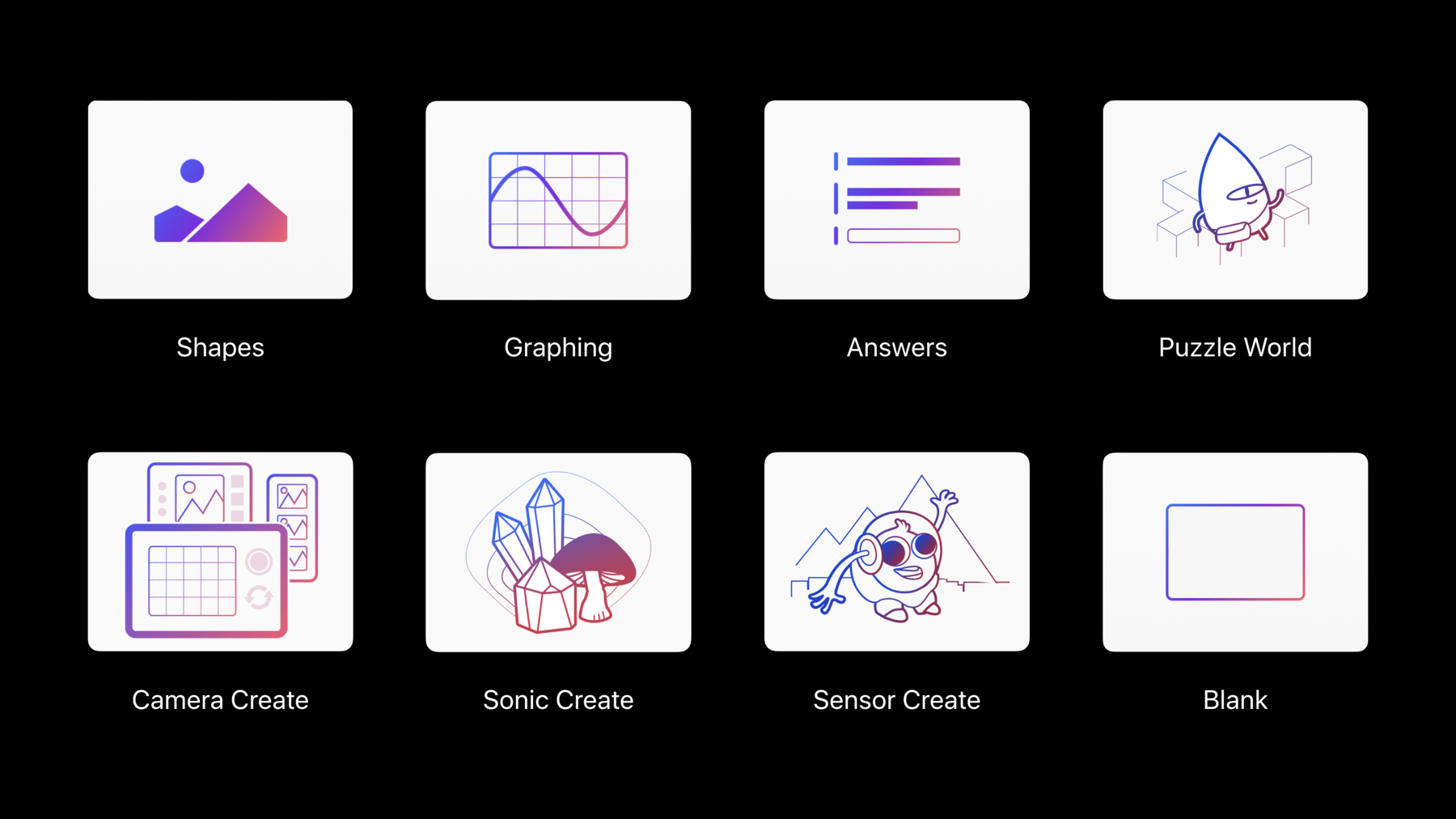

Apple has published six new pieces of content in Swift Playgrounds 3.

The Learn to Code family has expanded with Lights, Camera, Code, Assemble Your Camera, and Flashy Photos. These and the starting point Camera Create introduce the concept of building with components to create things like cameras and photo editors.

This Sonic Workshop challenge and Sonic Create starting point use touch events on iPad to compose music and create visual soundscapes.

Today, we'll be reviewing some of the exciting new features in Swift Playgrounds 3. I'll be going through the breadth of development that you can do just on iPad, and then Joy will talk about some of the new features available to authors on the Mac. But first, Jonathan is going to show us a demo that exemplifies the power of Swift Playgrounds 3 for developers. Jonathan? Thank you, Grace.

I would like to demonstrate how powerful this tool can be as a scratchpad for ideas with a little bit of fun. These devices are quite nifty. I am personally very excited about the sensors that it has like the accelerometer. I'm a big fun of games that use the accelerometer to do cool things and bring a sense of physicality to what's going on, on the screen. So, I'm going to show some steps that I took to build an infinite scrolling marble obstacle course from scratch on an iPad all in Swift Playgrounds. If you've ever played one of those tiny puzzle games where you've got a roll around a marble and not fall into any holes, it's just something like that.

We need a few things to make this work like a marble that response to the tilting motion of an iPad.

We'll need a procedurally generated map of holes that the player guides the marble pass. And to keep things simple, the goal is just to get as far as possible, as fast as possible without falling into a hole and out of the course.

There's a bunch involved in building something like this. I'm going to focus on a few steps in the process using, of course, Swift Playgrounds to read the raw accelerometer data, experimenting with the in line results to do that, using the live view to learn about the SpriteKit game in physics engine, experiment with how to do this procedural hole generation placement throughout the course, and then, we'll add it all up and take a look at the full prototype. Let's get started.

All right. Let's begin with a blank page. Every page in a Swift Playgrounds document is its own execution entry point. It's a main .SWF file. I love to use separate pages. It's like a journal of my travels as I'm trying to either solve a problem or learn a new API, just figuring something out. I'll start with one subsystem or working on a function or something over here, and then move to a new page. It's a completely blank slate where I can work on the next idea leaving behind a trail that I can return to further experimentation. Now, our chief mechanic is the tilting motion of the iPad. So, we should probably start by importing CoreMotion.

We'll create a CMMotionManager. Now, I'm using the Tab key of the hardware keyboard to select the different options in this shortcuts bar at the bottom for code completion. And then I'm pressing the Return key to select it. We'll tell the manager to start up by saying startAccelerometerUpdates.

Now, I don't know about you but I never remember which of the xyz coordinates of the accelerometer corresponds to how the iPad is supposed to move in this orientation. It's always confusing to me. But hey, let's figure it out right here.

We need to wait a brief moment before we can start. The accelerometer has to take time to spin up. We'll worry about reading this thing regularly later. Right now, we just want to get an experiment going to see if we get a value out of this thing. So, I will tell the manager that I want the accelerometer data, the acceleration property, and the x-coordinate. By putting it on its own line, this line gets logged, the expression gets logged and turns into an inline result on the right-hand side. We can see this here when I tap around my code.

All four lines get an inline result. I'm going to tap on the last icon here for the last line. Hey, we see a value, negative 0.78. That means something. Well, let me try this here. I'll tilt the iPad and try running it again and see what value comes out now.

It says, hey, negative 0.061. That's a different number. So somewhere in here, we're getting some sort of reaction that I think is related to the movement of the iPad. This is a start. But I'd really like to have some sort of real time feedback to give me an idea of what's going on. So let's fast forward to the next page where I've prepared an example to try out. Usually, when you run a Playground page, as the program counter reaches the very end, execution stops. You can restart whenever you want by just tapping around my code. And that's useful in many cases. But in this case, I would like the execution to continue so I can gather values over time. And because of that, I'm using the Playground Support API to tell the current page that I need indefinite execution.

We create the CMMotionManager just like before, we tell the accelerometer to start. And here, I wrote a simple function, just to helper function called repeatEvery that takes a trailing closure, calls the closure immediately, and then schedules calling it again after the given time interval but using the asyncAfter method on the name dispatch queue. It's crude a way of repeating things, I know. But, you know what, we're just experimenting and it works great. I can reuse this wherever I need to on this page. And I'm using it right here. Every half a second, this trailing closure gets called and as soon as the accelerometer data is not nil, we log the x-coordinate using that expression on this line. Let's take a look and see what happens when I tap around my own code. All right, we have things happening on the screen. Let me tap on the inline result and look what happens here. A graph representation is automatically selected for us because this is a sequence of simple numeric values. I'm going to pick this up and move it around. Whoa, we have things, stuff. All right. I'm going to try to get a baseline here. I'm going to hold it flat and then I'm going to tilt it upright.

I will tilt it down. OK. I think we've kind of figured this out. The x-coordinate of the accelerometer corresponds to movement along this axis of the iPad in this orientation. All right, there we go. I could do the same thing to figure out how y and z work as well. This is quite useful.

Now, this repeatEvery function . Thank you.

This repeatEvery function is nice. It's is crude of course but it's terse. It's clear. And I'm going to use it other places until I figure out how to do it the right way. That's fine. Well, because I created this as a blank playground in Swift Playgrounds 3, I have access to the new tabbed editing experience. Let me show you. I'm going to tap on the File icon up in the Navigation bar, and then I'm going to tap on the Utilities Module. This brings up the user module and source file picker. And you can see I've already done a lot of things in here as I was working on this idea. Well, in the Utilities Module, I'm going to put that function in here, make a Timing.swift file.

I'll tap on the Tab for the main file of the page to go back. I will tap on the repeatEvery function to select it. If I tap and hold, I can pick it up. And with my other hand, I will tap on the Timing Tab, and then let go to drop this piece of code as a copy in its place in this file.

Because this is a new file, Swift has no idea what time interval or dispatch queue you are, I'm going to have to tell it by importing foundation so it knows what to do with those symbols.

And because I want to use this function everywhere on every page and possibly even in other modules, I need to mark this function as public so it's visible. Now, I can go back to the main file, tap to select the function, delete it, and if I did it right, everything should work. All right, there we go. Yay. Now, I can open as many files as I need to, to experiment on different ideas. Like, let's try this one here, Math.swift. I threw a bunch of bits and pieces in here as I was going just to help me experiment.

These are math helper functions and a few extensions on system types that made writing the code more fluent at the point that I was using it, just part of the process.

I can tap and drag to reorder the tabs, tap the Close button to close them. And all of this code is available for use anywhere in this document. Quite convenient. Now, let's fast forward a bit more in this story. I've been poking around a bit with SpriteKit, refreshing my memory about how it works. Let's see how far I've gotten on the next page. I needed to bring up the documentation for SpriteKit. So I did that by tapping on the Tools Menu icon in the Navigation Bar and choosing Documentation. I searched for it by tapping on the magnifying glass and search for SpriteKit. By reading through this, I was able to refresh my memory of how this works, built up this body of code on the left-hand side of the screen. I learned about SpriteKit's scenes and nodes, that SpriteKit uses to layout everything in the game and render it on the screen. I learned about the physics engine and how you can apply forces to nodes so that the physics mechanism starts working over time. And I learned about the game loop when SpriteKit calls my code back on every frame so that I can affect changes in the environment. That last point is very important. Let me close the side panel and open up the Execution Controls Menu at the bottom. Because SpriteKit calls me back on every frame, I have to be quick, and I'm going to turn off the inline result. As we've seen, they're quite useful in many cases, but the logging of those expressions takes time. I don't want to slow SpriteKit down in this case, and I don't even need them. Because as you'll see, when I tap run my code, SpriteKit I set it up as the live view. SpriteKit itself is giving me the feedback that I needed while working on this part. And here you go, we have a circle shape thingy moving around in response to tilting the iPad. All right. Now, this is an important part of the story because-- thank you-- once you get something like this going, once you've got this kind of physical stuff happening on the screen, you've got to take this out and do user testing, right? So I took this to my kids. And as I started to tell them, hey, do you want to see something cool, they interrupted me, grab the iPad out of my hands and started looking at it, and tilting it around to watch it bounce around the screen. And they were amused. They said, "This is nice, father. This is very nice." But it's missing something. You see, there are not enough marbles on the screen. We need more marbles, lots and lots of marbles.

They have a future in project management, all right . This had nothing to do with my ultimate goal but it did sound kind of cool. We should get more marbles. So I added the tap, just to recognize and I sat down with them. We did this together. And so, every time you tap now on the screen, we insert a new SpriteKit node into the scene and add it to the physics engine so that it will participate in all the fun forces going on here. Now, this is usually how it went. The younger the child, the more furiously they would tap to try to fill this thing up as fast as they could and they wanted to see if it would crash. It didn't. And then they would just make this thing go and slosh it around. And I'm not going to lie, I find this absolutely mesmerizing. I can look at this all-- I'll do that later.

I would recommend you do it too. It's very relaxing. So anyway, we have SpriteKit now doing something in response to the accelerometer that's on the iPad as you tilt it around. This is close. We're getting a feel for how this game could work, and it's getting more and more exciting. But now, I need to figure out how to do this procedural whole generation. Now remember, this is a trench that has the holes laid out that the marble is supposed to go pass and avoid them. And we probably want to remember the holes that we put down. So if the user happens to scroll backwards for some reason, they can revisit the holes they saw before.

So let's jump ahead to see an experiment that I was working on. Now, while building this page, I decided to go into my game module and create a MapStruct. This goal of this type was just to calculate and remember where the holes go as you're proceeding through the course. It basically breaks up the map into a grid of columns and then places the holes inside there. It's really simple. This could easily be swapped out for something more intricate or complicated if I want. Eh, it works for now.

And also in the Game Engine Module, I created a MapNode that receives a map and knows how to layout the whole nodes at different points along the course. All you have to do is pass it a rectangle that represents where the camera is and the viewport of the-- that the user sees. As soon as you do that, it will render the holes in that spot reusing nodes if it needs to. It kind of acts like UI table view, stuff like that. So, let me run the code here and we'll see how this works. We get some inline results on the right-hand side, and I'm going to tap to view this preview. I wrote this preview method on the MathNode myself because I wanted to generate an SKView, the UIView subclass that shows SpriteKit scenes. I wanted to generate it and put it here so it can just show up as a static inline result. I didn't have to build any extra plumbing to show this up. It's just right there ready to go. And now, we see if the whole diameter is 20 points wide and we're at this point in the course, this is the map density you'll get. I can experiment with this density anyway I want and tweak the values here, jump into the other files and tweak those two. And the inline results gave me the feedback that I needed at this point.

Now, we're ready. Let's skip ahead even further to the final point where we see the game. Now before I start, I have to turn off the inline results again. As before, we're doing a lot of work on every frame. And we don't need the expression logging and we don't want it to slow us down. I'll tap around my code, and there it is. We have a marble looking thing on top of a wall looking thing with parallax. Look at this, lovely stuff. Now, when I was working on this idea, Joy reminded me that there's a bunch of textures that I can grab out of the templates that you can download right in the app just, you know, grab those resources and have fun with them. So I pulled up the sensor create template, used the asset picker, pulled out some of these textures and dropped them in my app. And here they are. I even went over to a-- an image editing app to find-- there we go, make some fuzzy looking hole shape things. Oh, that's all right. It's amazing what radial gradients can do. It's so cool. Here, let me tap in the middle and make this full screen by dragging the midpoint all the way over to the left. And I'm going to try this again. I added the tap recognizer to start over if the game ends. And let's see how far I get. The faster you go, the faster it increases the score to add a little bit of recklessness to the fun here. Whoa, OK.

It's really hard to do this in front of a crowd .

But, hey, you know what, all of what you've seen here, each step leading up to this point was done entirely on this iPad. This was a lot of fun. My family had a great kick out of it. I learned more about SpriteKit. I had a chance to use the new user module and source file support in the app to break up what I was doing into different pieces. It was a fantastic experience. Swift Playgrounds on iPad is a great scratchpad to try out your ideas, maybe even look and use our APIs and see how they work, or even increase the stress in your life by building speed running games to play with your friends. And now, I would like to invite Grace back up to the stage so that she can talk about how this stuff works and do a deep dive into how you can use these new features to make the most of Swift Playgrounds 3. Thank you. Thanks, Jonathan.

So, if you're already familiar with Swift Playgrounds, you might have noticed a couple of new things in Jonathan's demo. Let's go through those now. Most notably is the addition of Modules, which allow you to separate your code into multiple Swift files.

Modules are represented as directories of Swift code that can be used by any page in a book. And you don't need to worry about setting targets or making new build settings. Users can add modules to books as well as Swift files to any module.

Be aware though that if you reset a document, all of the user edits are reset as well. And this does include any added files or modules.

So with the opportunity for all of these new files, let's go through the structure of a Playground. I'll be using the shapes template as an example.

Each book has a set of pages, and each book can also have multiple modules. Each of these modules in turn can have multiple source files.

So, let's quickly talk about the access levels between all of these different Swift files.

Code in pages is not shared to other pages within a book. That is to say, the code on the Canvas page is not shared with the code on the Create page.

However, every module is automatically imported into each page. This means that the code in your modules is accessible on every page as long as that code is marked as public. Files within the same module have access to each other without needing to mark code as public. However, if code is marked as private, it won't be visible to other files in other modules or pages. It'll just be private to that file.

Code between modules is not shared by default.

But let's say I have some code in my Graphics Module that I want to reference in my Calculus.swift file which is in my Math Module.

All I have to do is make sure the Graphics code is marked as public, and then import the Graphics Module into my Calculus.swift file. With modules, you'll still have access to inline results and step through execution. So you can watch the path that your code takes between all of your files.

As the app steps through your code, it automatically switches between the files where your code is executing.

You can also turn off inline results which can speed up execution as we saw in Jonathan's demo.

You can find this control within the Execution Control Menu along with Step Through My Code and Step Slowly.

The new Issues popover can show you errors throughout all of your files in a document and allow you to easily navigate between them. If you tap on any of the errors, it'll take you right to the corresponding line, both for builds and for runtime errors.

Swift Playgrounds support Swift 5 and the iOS 12.2 SDK.

This lets you play with frameworks like Core ML 2 and ARKit 2, developing for iOS right on iOS.

So now, all from a blank Playground, you can add pages through the Table of Contents popover, add modules, and add Swift source files to those modules all without ever leaving the app.

So there are also lots of ways to customize your content, like setting module modes, adding localizable code comments, and changing what files the user sees when they open your document. So I'd next like to invite my colleague Joy to the stage to tell you how.

Thanks, Grace.

Next, let's talk about all the new features authors can customize in Xcode whether you're sharing your Playground directly or through a subscription.

When I'm teaching, it's important for the tools I give my students to be leveled appropriately and as user friendly as possible.

In order to create the right tool for your audience at any level, there's several features you can take advantage of in Swift Playgrounds 3 to highlight the most important parts of your Playground and remove unnecessary complexity.

All these new features can help you create more engaging content and give your learners a friendly experience in a real developer tool.

First, let's dive into the Module Modes. Now, you've heard a lot about Module Modes in the app from both Jonathan and Grace.

As an author, you can decide what Module Mode is right for your book.

Because all modules are an exciting new feature, not all books will benefit from the use of modules. And for that purpose, we have three module modes: None, Limited, and Full. The Module Mode you choose will change the nature of your book fundamentally, and should be considered the foundation of your user experience.

Let's start with the module called None.

This mode gives your students the original Playground experience, not allowing any access to user modules. This mode relies completely on pages and chapters to advance the story and code. And each page works completely independently so no user code is shared between pages in any way.

In the Module Mode None, all of the code in your book will go into the Modules folder.

This will create private modules that can be referenced in your Playground book but not editable by your students.

You can use private modules in any of the three modes. However, the difference in the Module Mode None is that all of your code will go into private modules.

As you build your book, keep in mind that pages and chapters are intended to be experienced linearly. As the author, you should think about what the goal is for each page, and have each page culminate in something new, you can do or see in the live view.

This will give your learners a tight feedback loop ensuring they know they've completed the task and they're ready to move on.

To see examples in our library of Module Mode-- of this Module Mode books, you can check out Learn to Code 1, Learn to Code 2, Lights, Camera, Code, and a variety of our challenges. Now, Limited Mode is your first foray into user modules and shared files.

Limited Mode allows for a single user module. And unlike private modules. user modules are completely editable by your students.

The shared files in a user module persist throughout the book and they're placed to build up code over time.

With access to a single module, your students can learn how to manage multiple files and bugs coming from files they don't necessarily have open. Within your one module, you can provide as many shared files as you want and your learners can edit, create, or delete any of the shared files within their user module.

As the author, you can also use private modules to include API you don't want to be editable by your students in the modules directory. As you saw in Jonathan's demo, he did several math functions to a single Math.swift file.

Adding new shared files is a great learning opportunity to teach how to organize code in logical ways.

You can teach your students to move code into a shared file they'll build up over several pages, or move aside code they'll change in frequently.

To see examples in our library of Limited Mode books, you can check out Blu's Adventure, Assemble Your Camera, Flashy Photos, and a variety of the challenges, some of which you see here. And if you want all the bells and whistles, you have Full Module Mode.

This mode gives you all the tools available, including making multiple modules, and new files within those modules. This mode is perfect for teaching code architecture and organization. In Full Module Mode, you cannot only teach how to manage multiple files, but multiple modules, and importing those modules into each other when necessary.

In Full Module Mode, you can still use private modules and as many prebuilt user modules as you want.

Full Module Mode also gives your students the freedom to extend those user modules and make user modules of their own.

When you're authoring for modules, you should consider when you might want to use a private module versus a user module. By putting all the code into a user module, your students can go beyond simply just playing in your Playground to seeing how it's built.

It also gives them complete control to tinker and remix, giving your students a chance to go beyond just being a student to getting that much closer to becoming app developers themselves.

To see examples in our library of Full Module Mode books, check out any of the starting points.

And to specify which module mode you want your book to full under, you must edit the key UserModuleMode in the book level Manifest.

Another customization you can do when using modules in Limited and Full Mode is auto-opening and activating files on a page by page basis.

Now, that you can expose multiple files in a tabbed editor experience, you can specify which files will be opened and which one will be active when you arrive on a page. To add open files means that main.swift will be the active file, but there may be other files open as tabs in the editor.

Providing the user with open shared files when they arrive on a page will help them know which files they'll be editing or need to reference without having to locate those files themselves in the files' popover.

You can specify which files will be opened on a per page basis in the page of a Manifest.

In the Manifest, used the key UserModuleSourceFilesToOpen followed by an array of shared files.

The value of each item should be the relative path to a shared file. In any case that you opened files, the default action is for main.swift to be the front most file or the active file.

However, if one of the shared files is going to be the first or most prominent place your user will be working, you can set this file to be active when they arrive on a page.

To declare a shared file to be active, use the key UserModuleSourceFileToActivate again in the page level Manifest.

The value of this key is the path to a single shared file.

Now, Code Completion is something you've always been able to do in main files. Now, in Swift Playgrounds, let's see how Code Completion has been extended to shared files.

Code Completion Directives determine what API is exposed in the Shortcut bar.

The Shortcut bar can be a helpful tool to keep your learners on track, minimize the time they have to type, and ensure they always know what to do next.

In the introductory content, you want to lower the barrier to entry by enabling your students to tap through most of their code.

In more advanced content, you want to expose API at the right times.

As the author, you can control what appears in the Shortcut bar on a page by page basis in both main and shared files. In order to manage these completions, Swift Playgrounds now offers two places you can provide Code Completion Directives.

Let's start in a place you might be familiar with in the main.swift file.

Now, this is just the start of what you'll see if you don't have any Code Completion Directives in the new content, Assemble Your Camera.

To ensure you have full control over what appears in the Shortcut bar, you want to start with a directive, everything, hide. Just as it sounds, this will hide everything from the Shortcut bar giving you a blank slate to work from.

To start building suggestions back into the Shortcut bar, you can use currentmodule, show. This is a special keyword that you can use to ensure everything you or your students create on the main file is shown.

The directive module show, followed by comma separated list of modules will show everything marked as public in those user module files, as well as any new code a user may write while playing in your Playground.

This is the same directive you would have used to expose a library like UIKit.

For more information about the various directives, please check out the documentation for Swift Playgrounds.

And newly added in Swift Playgrounds 3 is how to add Code Completion Directives in a shared file in the page of a Manifest.

This means that just like how you can scaffold what API is exposed in the main files as your students move through your book, you can do this in shared files as well, ensuring you won't overload your learners at the start of their journey. To do this, you'll use the key UserModule CodeCompletionDirectives followed by an array of Code Completion Directives similar to how you would make them in the main file.

Again, if using everything hide, you want to use currentmodule show and module show, to show everything created on the main and shared file. Additionally, you can add keywords like public and private as identifiers to show these to your students as they start new functions, classes, and structs in a shared file.

Next, let's talk about making Cutscenes in Swift.

Several of the books in the Swift Playground's library use Cutscenes to introduce a new skill, engage the user, or summarize a concept.

What was previously only done in HTML, you can now also write in Swift.

This offers loads of benefits to you as a developer.

You can leverage frameworks like SpriteKit, UIKit, and CoreAnimation.

By using Swift, you don't have to switch tools to create Cutscenes which means you can use the Interface Builder for storyboards and auto layout.

And you can localize your Cutscenes using the same tooling you use to localize your content.

Using Swift, you'll now add Cutscenes to your book similar to how you would a new page.

In the Pages folder, you'll still need a folder ending in .cutscenepage, only now you'll need both a .swift file and a Manifest.

The .swift file you include behaves like a liveview.swift file and should run and present a live view.

In order for your Cutscene to appear in the Table of Contents, you add it to the chapter level Manifest, just like you would a new page.

Now, finally, I'm excited to introduce you to Localized Code Comments.

If you're distributing your Playground book to multiple locales, you can now localize code comments and strings in any main or shared files. This means that your book will be fully localized to your students.

For code comments, you can have a single or multiline comment in a localizable-zone. Each localizable-zone should have a unique identifier.

You can also use inline localizable-zones to make string literals localizable. The output of your Localized Code Comments will be stored in the LocalizableCode.strings file in the book level Private Resources folder.

That's a taste for all the powerful new features in Swift Playgrounds 3 for authors. Next, let's see all these new author and app features come together with the demo from Grace.

So with all of these new features, I really wanted to show off that you can create something super robust and fun for Swift Playgrounds on the iPad.

So as you all know, the general workflow for creating an app that incorporates the iOS camera on iPad is to start with a blank app in Xcode on the Mac, write some code, run it on your iPad, see if it worked, and then iterate back and forth between your two devices. But, you can iterate much more quickly if you're writing the code right on the iPad itself with Swift Playgrounds.

So I wanted to use the Vision framework which does use the camera along with Core ML to do object detection and live capture. So, Swift Playgrounds was actually a great place for me to build this app.

So there is a concept in American Sign Language of name signs which are special signs to uniquely identify a person. When I was little, my mom gave me the name sign of this which is the letter G and a smile. But that is me on the left not smiling. So maybe it should have been more like this. So working off of this idea, I created a piece of content that incorporates some doodling and some sign language recognition which I want to show you now.

All right. So, here's my piece of content packaged up into a book that I call Sign Me Up. So what I wanted to do was make something to let Jonathan, Joy and I create a unique face painting for ourselves and then trigger those drawings with sign language.

So, I'm doing touch recognition to draw on live video output and then I'm using the Vision framework to track those drawings to detected faces. And then I'm using Core ML to do object recognition and live capture to rotate between those drawings based on what's being signed.

So I created my book and I put it in Limited Mode so I can hide away some of the implementation details. I really just want my users to focus on a few of the Swift files I've created in my user module. On the Mac, I trained a Core ML model to recognize three signs. So G, Y and N, then I imported the model to my iPad into this Playground.

So G is for Grace, and my co-presenters Jonathan and Joy, both have the same first two letters of their names so I settled for the third. So Y for joy, and N for Jonathan. So I'd like to invite them both back up now to demonstrate.

Alright. So on the first page, I added some pros instructing the user what to do. And when Joy taps in the Source Editor, you'll see that I've added a code completion directive to suggest the setColors function.

Just by tapping, she can fill this function out by selecting color literal placeholders in the Code Completion bar. The quick editor for this makes it super easy to see different UI colors this way.

The setColors function sets some of the different drawing colors that will be available once she runs the code. So let's go ahead and do that now.

Awesome. And let's expand the live view to full screen to get a better perspective.

So she'll cycle through in the bottom, left-hand corner to set Y for Joy, and then can tap through in the right hand color to pick the color to draw with. And then she can do some face painting.

So what she draws is tracking to her face using the Vision framework which can return a bounding box of a face and some facial landmarks. So I'm using the left pupil to map all of these points to their correct locations.

Once she's satisfied, she'll tap Done and give Jonathan a turn.

So these drawings are then represented as a set of colors and x, y distances to the left pupil and are then mapped to a letter. This information is then saved to the Playground key value store of this Playground. And all of this code for the mapping is in the FaceView.swift file and is available for the user to peruse without messing up any of the cleanliness of my main page. So it looks like Jonathan's done. I'll follow suit.

Cool.

Awesome. So let's go to the next page now which instructs us to run the code and see what happens. And let's bring the live view to full screen again to get a better perspective.

So, so far, nothing is happening except for our face detection. But try signing the letter Y.

Awesome. So Swift Playgrounds is recognizing-- Yeah.

Swift Playgrounds recognizes that Joy is signing Y and is projecting her drawing onto her face. So let's see if we try a different letter. Let's try G.

Oh, I don't know. Rotate a little bit.

Oh, we're getting there. Maybe N for Jonathan. There we go. Cool, cool. And it can even switch between faces.

Perfect. You've never looked better . So, all of this code was written entirely in Swift Playgrounds and is running on this iPad. And you can customize it for your students, your friends or fellow developers on the Mac making for unique and really fun piece of content that makes Swift Playgrounds accessible.

So both Jonathan and my Playgrounds are available for download online in a subscription at wwdcswiftplaygrounds 2019.github.io.

And for more information, please check out our documentation developer.apple.com. And please come to the labs tomorrow morning, bright and early at 9:00 a.m. We're going to be there and we'd love to talk with you. Thank you all for coming and have a great rest of your conference.

[ Applause and Cheering ]

-