-

LLDB: Beyond "po"

LLDB is a powerful tool for exploring and debugging your app at runtime. Discover the various ways to display values in your app, how to format custom data types, and how to extend LLDB using your own Python 3 scripts.

리소스

관련 비디오

WWDC22

WWDC21

WWDC18

-

비디오 검색…

Hello, my name is Davide and I am an engineer on the Debugging Technologies Team at Apple. I'm here with my colleague Jonas. You might be familiar with po, a way to print variables in LLDB. Today, we will talk about it and how it works. We will also present other ways to look at the variables in your source code together with powerful mechanisms to format the output. LLDB is the debugger that powers the variable view in Xcode.

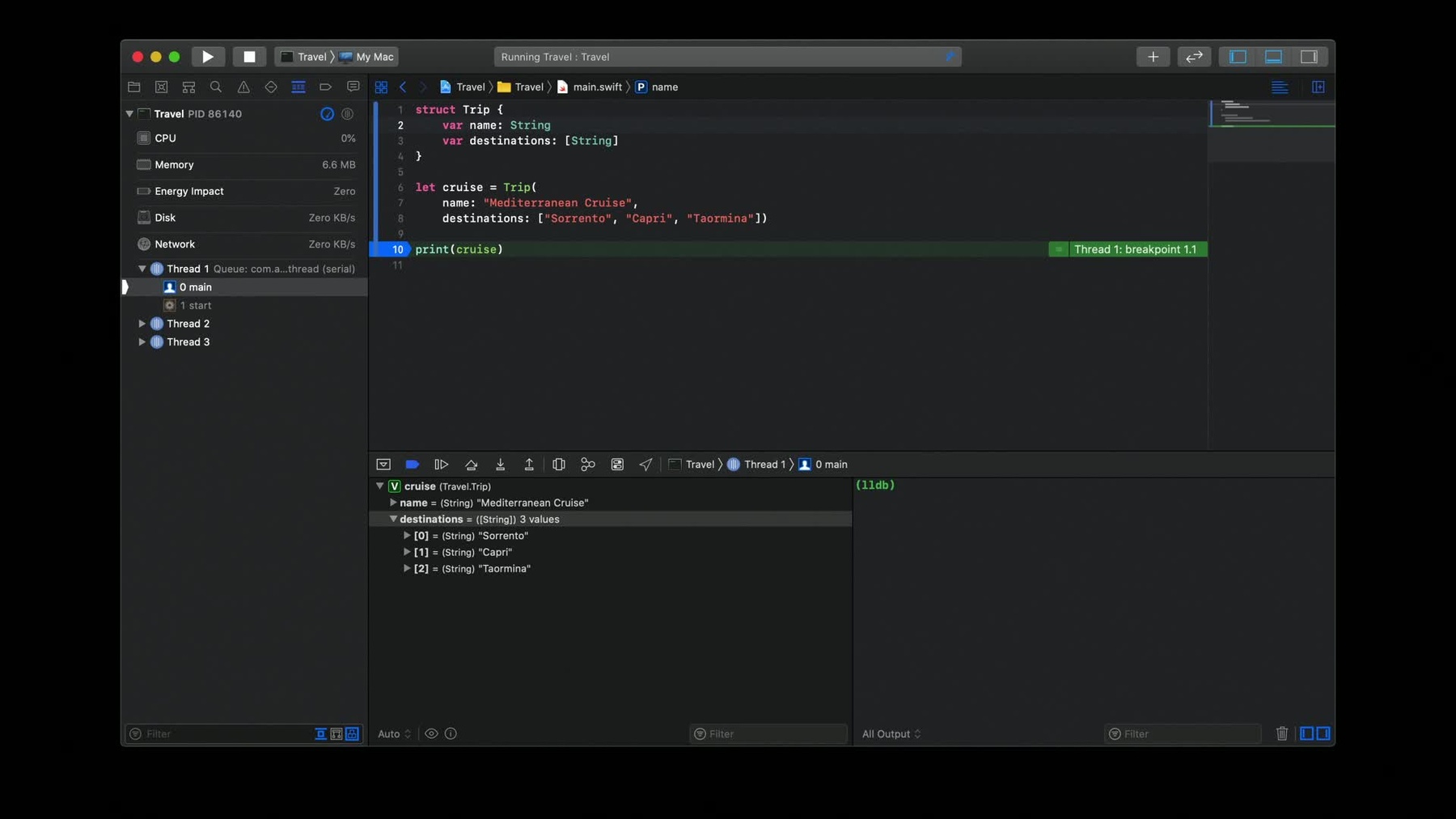

You can see the variables you define and their types there.

While debugging in Xcode, you can also directly send commands and interact with LLDB through the console in the bottom right of the window.

This includes the ability to print the values of the variables to defining your source code while you're investigating a bug in your application. LLDB offer several ways to accomplish this task. Each of which comes with a different set of trade-offs. Let's look at them. As an example, suppose we have a struct that represents a Trip, consisting of a name and a list of destinations. Let's go on a cruise around the Mediterranean.

The first command we are going to explore is po, which you can think as of standing for print object description. When we use this command, what we get in return is the object description which is a textual representation of an instance of your type. The system runtime provides a default one but it's possible to customize it.

We can do this by adding a conformance to the CustomDebugStringConvertible protocol. This requires having a single property called the debugDescription.

Now, if we print the object description in the debugger, we'll see the description we provided instead of the default one.

The change only affects the top-level description. If you need to modify the substructure, check the documentation for the CustomerReflectable protocol.

This can also be done for Objective-C objects by implementing the description method.

But po does more than just print variables. For example, you can take the name of our cruise and compute an uppercase version of it or get an alphabetically sorted array of the cruise destinations.

In general, it can evaluate arbitrary expressions. So, anything that would compile at a given prompt in the program can be passed as an argument to the comment.

In fact, po is actually an alias for a command called expression with an argument for printing the object description. LECC and LLDB are a convenient way to save keystrokes. If you wanted to implement po yourself, for example, you could use command alias. Specify your own command name as the first argument, and then follow with the command you want to alias. Once that's defined, you can use it like any other commands in LLDB.

Now that we know what po can do, let's take a deeper look at how it works.

Let's go through the steps that po has to perform to deliver a value. To provide the full expressivity of the language you are using LLDB doesn't parse and evaluate the expression itself. Instead, it starts by generating a piece of source code that can be compiled from the expression you gave it, similar to the snippet shown here. Then it uses the embedded Swift and claim compilers to compile the code which gets executed in the context of your debugged program. Once the execution is complete, LLDB has to access the resulting value.

From there you need to get the object description. To do this, LLDB wraps the previous result in another piece of source code. This also gets compiled and executed in the context of your debug process. The result of this execution is a string that LLDB will display as the result of the po command. Po is only the first of the three ways we are presenting to print variables in LLDB. Let's look at the others. The second way to print variables in an LLDB is the p-command. You can think of it as print without the object description. Let's look at its output.

The first thing to notice is that the representation is slightly different from the one provided by po, but it is equivalent in that it contains the same information.

The second thing to notice is that the resulting value has been given a name, $R0. This is a special convention in LLDB. The result of each expression is given an incrementing name, such as $R1 and $R2. And this name can be used in later expressions in LLDB. You can refer to $R0 the same way as any other variable in your project. You can, for example, print the fields of destruction.

Similar to po, p is not a first-class command in LLDB. It's just an alias for the expression command, but without the -- object description after it. As we previously did with po, let's look at how po works under the hood.

Since p doesn't have to get the description, it doesn't have to do as much work. You may recall this diagram from the earlier description of po. In fact, the first part compiling and evaluating the expression is exactly the same for both commands. But once it gets the results LLDB perform a step name dynamic type resolution on it.

Let's describe it with more details. In order to do that, we have to modify our code example a bit. Let's see how.

We change our Trip struct to conform to a protocol name activity.

In Swift, the static representation of a type in the source code and the dynamic type at the runtime, aren't necessarily the same. For example, a variable might be declared using a protocol of this type.

In this example, the static type of cruise's Activity. But at runtime, the variable will have an instance of type Trip which is the dynamic time. If we print the value of cruise, we get back an object of type Trip because LLDB retell results metadata to display the most accurate type for a given variable at a given program point. This is what we call dynamic type resolution. With the p-command, dynamic type resolution is only performed on the result of the expression. Let's say we want to access one of the field of cruise. When LLDB tries to evaluate this expression through p, it sees that cruise is an object of type Activity and doesn't have a member called name. The evaluation fails with an error. This happens because if you remember, LLDB compiles code where running p and the only type it sees is the one in your source code, the static one.

It's the same thing as typing the expression cruise.name in your source code. The static compiler will reject it with an error. If you want to evaluate the expression without errors, you need to first cast the object explicitly to its dynamic type and then access the field on the result. This is true both for the debugger and your source code.

P is not yet done with its work. After it performed dynamic type resolution on the result, LLDB passes the resulting object to the formatter subsystem which is the part of LLDB responsible for printing a human readable description of objects. Let's dive into it.

To show how formatters work, we're going to display their input and output. Here's what that string looks like if there was no formatter for the type.

If you want to try yourself, you can pass the -- raw option to p. Standard library types even simple ones like strings and integers have complex representation because they are highly optimized for speed and size. After the formatter operates in it a string looks exactly as you expect, a sequence of characters. LLDB knows about a bunch of commonly used types and provides formatters for them. You can also write for customize formatters. We'll talk about it shortly.

We talk about p and po.

We are now going to describe the third way to print variables in LLDB, the v-command.

The output of v is exactly the same as p as it also relies on the formatter we just described.

As with the other two commands, v is just an alias we introduced in Xcode 10.2 for the frame variable command. Unlike the other two mechanisms, the v-command doesn't compile and execute code at all which makes it very fast. Since v is not compiling code, it does its own syntax which will not necessarily be the same as the language you are debugging. For example, it used the dot and subscript operators to access fields over time. But it won't perform overload the resolution and computed properties cannot be evaluated since that would require code to be executed.

You can use p or po if you need those. As you can guess, v works fairly differently from the other two mechanisms for printing variables. Let's go ahead and clarify some details. In our grand tradition of diagrams here is one for v. We want to print a variable. To do so, v first consults the program state to locate the variable in memory. Then it reads the value of the variable from memory. Then it performs dynamic type resolution on it. If the user asked to access subfields, it repeats the step for each of the subfields performing dynamic type resolution at each round. Once it's done, it passes the result to the data formatter subsystem. The fact that v performs dynamic type resolution potentially multiple times is an important detail to remember and the big difference in the way p and v operates. The formatter indeed performs dynamic type resolution only once. Let's look at the scenario where these matters.

We are back to our example where p was failing to access the member of cruise. By performing dynamic type resolution at each step of the interpretation, v is able to understand that cruise is an object of type Trip and access its field in memory. This is a scenario where v is strictly more powerful than p and allows you to look at your types where p doesn't or without an explicit cast.

We are done describing the three different ways for printing variables in LLDB.

Let's have a recap and the side-by-side comparison of how the po, p and v commands differ.

The first point we want to make is about how objects are presented.

The po command uses the object description, whereas the p and v commands use the data formatters to display the object. We also want to remember how our results are computed. Both po and p compile expressions and have access to the full language. V instead has its own syntax interprets the expression and performs dynamic type resolution for each step of the interpretation.

We mentioned earlier that LLDB formatting can be customized. To talk more about that, here is my colleague Jonas. Hi, I'm Jonas, and I'm also an engineer on the Debugging Technologies Team.

In LLDB, data formatter is defined how variables are displayed in the debugger.

There are building formatters for common types. For instance, when using the v-commands, we can print the destinations of our cruise and the array elements are displayed in a readable format.

Usually, the default formatter works great for both the user defined types and for types coming from the standard library. But sometimes you might want to tweak an existing formatter or to find one yourself.

And you can, because data formatters in LLDB are fully extensible. Every type can have its own representation. To help you customize that representation, LLDB offers filters, summaries and synthetic children.

Filters are used to limit the output of existing formatters. Right now, our Trip only has a few destinations but as the number increases, the output could become cluttered.

By adding a filter, we can specify that we only want to see the Trips name.

This not only affects the output of the formatter in the console, but also the variables here in Xcode.

Let's remove the filter again before moving on.

Summaries provide a string representation of a type. To give information about that type at a glance, their data formatter equivalent of the description that you would implement for use with po. As with filters, they also affect the variables view in Xcode.

While the members of our Trip all have summaries, the Trip itself does not. Let's change that.

A good summary would be the first and last destination.

The summary string can contain regular text and special variables that access fields of the time being printed. These variables start with a dollar sign and are wrapped in curly braces. They use the same syntax as the v-commands. The current type for which the summary is defined is access as var.

The summary uses var.name to access the Trips name and var.destinations to access its destinations.

But there's a problem with the summary. It only works for Trips that contain exactly three destinations. Because formatters can't access computed variables like the count of an array, we have to hard-code the index of the last element.

Fortunately, there's another powerful tool available to us. We can also define summaries in Python.

Python formatters can do arbitrary computations and they have full access to LLDB's scripting bridge API which provides several objects for accessing the state of the current debug session. The target is the program that's currently being debugged. The process, thread, and frame provides access to the corresponding runtime information.

Values of variables, registers, or expressions are represented by the SB value class. These are particularly interesting to the data formatters because they are used to navigate types and their values. Check out the online documentation for more details.

Starting with Xcode 11, scripting uses Python 3. If you have existing Python 2 scripts, check out the Xcode release notes for more information on transitioning to Python 3. Let's explore the LLDB API.

Executing the script commands drops this into an interactive Python interpreter.

The current frame is accessible to the lldb.frame variable. This returns an SBFrame instance. We know that the current frame contains a variable named cruise. So, we can go ahead and use find variable to obtain its SB value.

Since these objects power the data formatters under the hood, it is no surprise that printing them looks identical to the corresponding data formatter outputs.

We also know that cruise has member named destinations. We can access it by calling GetChildMemberWithName.

The result is another SB value that represents the destinations array. Let's try to mimic our earlier formatter using Python, this time without hard coding the index of the last element.

We can use GetNumChildren on the destinations SB value to get the number of elements. With GetChildAtIndex, we can access the first element and the last element.

Notice that the printed values are context sensitive. They contain the index in the array. SB value instances maintain the context of their parent relation.

Now, we can put everything together in a single string. The results, however, it's not exactly what we want, by printing, begin and end, we get descriptions of the SB value objects. What we really want here are their summaries. We can use GetSummary to retrieve the formatted value and use that instead. Now, the result is place only the destination strings themselves. Let's put everything together. Formatters can be defined directly in the debugger console or you can use a file and load it into LLDB. In this case, we'll create a file called Trip.py.

When defining a provider in a file instead of using the current frame to access the variable we want to display the SB value is passed as an input parameter to a function.

The rest of the implementation is pretty much identical to what we did before.

Another advantage of using Python to define the formatter is that we have control flow. If the trip has no destinations, we can just sprint that it's an empty trip.

We get the summary for the first and last destination and return to summary string.

Now, we need to load our new summary provider into LLDB. This is done using the command script import command.

Next, we need to specify that our new formatter is the one to use for the Trip type. Using type summary add and providing the type to be formatted, and the provider function to use.

It's important to use the fully qualified type here. With everything hooked up v now uses the Python summary provider to print a cruise object.

Not only does the summary show up in the console, it is also displayed in Xcode's Variable View. We've talked about filters and summaries. The final way to customize the display of your type is with synthetic children.

These make it possible to customize what kind of children your type exposes, such as when you expend to type in the variables view in Xcode.

In Python, each child has an SB value, and each can have its own summary.

Defining your own synthetic child provider is similar to defining a summary provider. But instead of a function you define a class that implements certain methods. In addition to init, you provide a method to get the total number of children, the synthetic children themselves, and an index for a given name.

A full example of this is available in the resources link from this session.

Just like before, use command script import to load the Python source code into LLDB. In this case, we already loaded this file earlier and running the command again will reload the file.

To specify the formatter, to use for synthetic children use type synthetic add and provide the type to be formatted and the class to use.

After going through the effort of defining our own custom providers, we don't want to lose them at the end of our debug session.

Any command you type in the console can be persisted in the .lldbinit file in your home directory.

This file gets automatically loaded at the beginning of your debug session.

LLDB has a variety of features to help you see the state of your program while debugging. Use v, p, or po to print variables, depending on whether you just need to display its value, execute code or get the object description.

Customize or define your own data formatters, using filters, string summaries, and synthetic children. Finally, if you have scripts written in Python 2, update them to be compatible with Python 3. The version used by LLDB starting in Xcode 11.

For more information, check out the page for this session on developer.apple.com.

-