-

Get to know Metal function pointers

Metal is a low-level, low-overhead hardware-accelerated graphics framework and shader application programming interface for producing stunning visual effects in applications. Discover how to make your shaders written in Metal Shading Language more programmable and extensible by using function pointers. Learn how to take advantage of this new feature for dynamic flow control in Metal shaders. Discover how to use function pointers to specify custom intersection functions in your ray tracing application. We'll explain how function pointers allow several compilations models so you can balance GPU pipeline size against runtime performance.

리소스

- Modern rendering with Metal

- Accelerating ray tracing and motion blur using Metal

- Metal for Accelerating Ray Tracing

- Debugging the shaders within a draw command or compute dispatch

- Metal Feature Set Tables

- Metal Performance Shaders

- Metal

- Metal Shading Language Specification

관련 비디오

WWDC21

-

비디오 검색…

Hello and welcome to WWDC.

Hello everyone. My name is Rich Forster, and I'm a GPU software engineer at Apple. In this session, I'm going to talk to you about the new function pointers API that we've added to Metal this year. Let's start with the humble function pointer.

Function pointers give us the power to refer to code that we can call. They make our code extensible by allowing us to write our code so that it can later call code that we have never seen before.

The classic example is the callback, where execution jumps to code identified with a function pointer. This lets us provide functions for plug-ins, specializations or notifications. But we can do so much more. Today I am going to talk about how we expose function pointer support in Metal and how we use visible functions to achieve our goals. I will cover the different compilation models we support, what they mean, and when to use them. I will then discuss tables of visible functions and finish with a discussion of performance. So let's start with function pointers in Metal.

When we added function pointers to Metal, we knew there would be a range of opportunities to use them. The obvious case is ray tracing, where we use function pointers to specify our custom intersection functions. And I would encourage you to watch the ray tracing talk which accompanies this session.

Ray tracing is also a great place to talk about other uses of function pointers, and that's where I'd like to start today.

When we apply ray tracing to the classic Cornell Box, we fire our rays into the scene, and when they hit surfaces, we need to shade the intersections. Typically, we have the material for the surface that we intersect, and then we will continue tracing until we hit a light, at which point we will evaluate the contribution of the light. Let's revisit the process flow for ray tracing. First, we generate rays which start from the camera and are emitted into the scene.

We then test those rays for intersection with the geometry in the scene.

Next, we compute a color at each intersection point and update the image. This process is called shading.

The shading process can also generate additional rays. So we test those rays for intersection with the scene and repeat this process as many times as we'd like to simulate light bouncing around the scene. Today, we're going to simplify things for this presentation and start by considering a path tracer that performs a single intersection and then shades the result of that intersection. This will be in a single computer kernel that creates a compute pipeline that includes the code for each of these three stages. However, the stage I want to focus on is shading. This is the last step before we output our image and provides a range of opportunities to use function pointers.

Within our ray tracing kernel, shading happens near the end.

Once we have an intersection, we find the matching material and perform our shading for that material. In this example, all of our material and lighting code lives in the shade function which exists elsewhere in our file. Let's dig deeper into the shade function.

Our shade function has several steps.

This is a simple path tracer, so it immediately calculates the lighting from the light at the intersection point on the surface.

And then we use the material to apply that lighting at the intersection point.

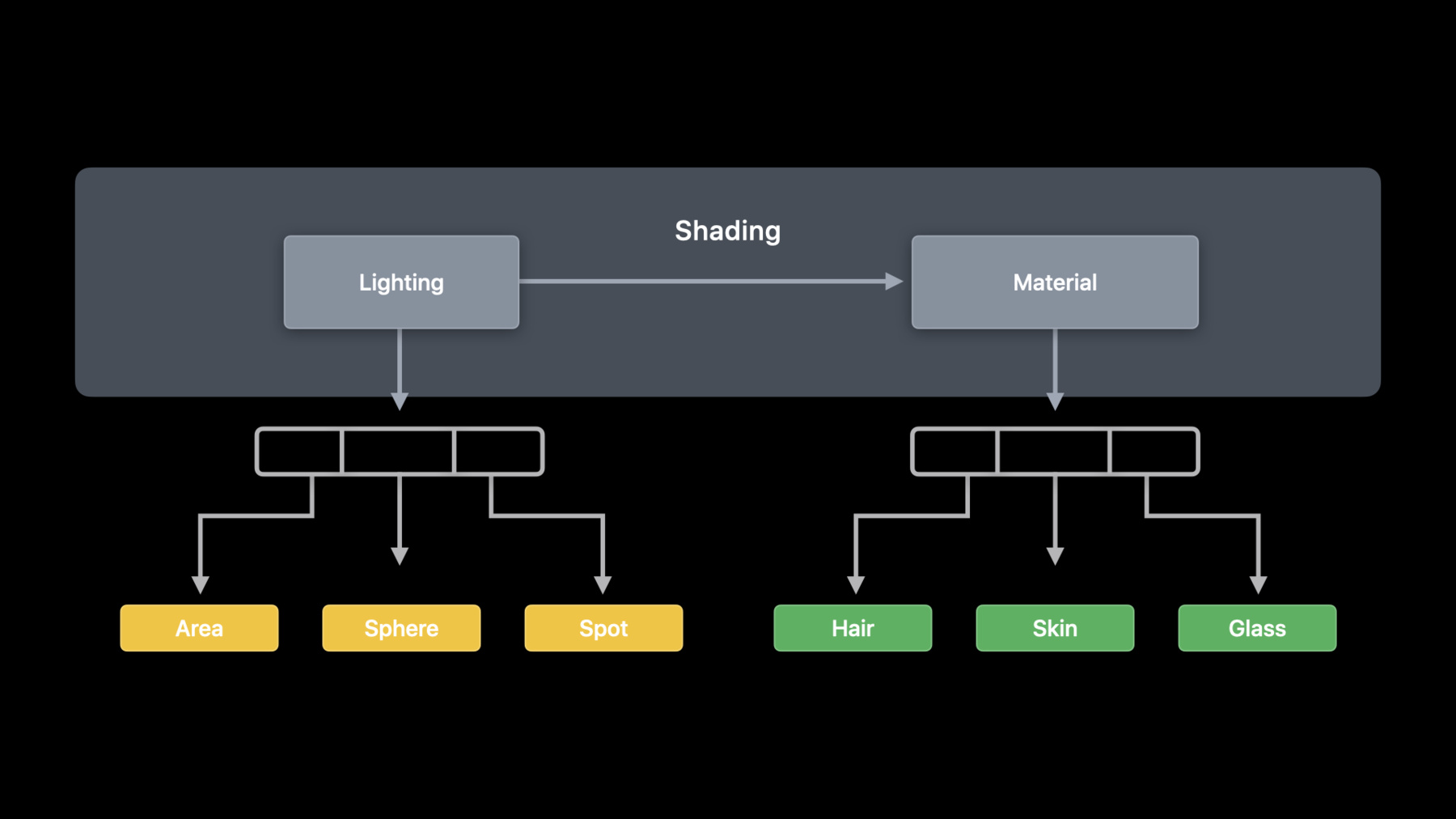

In terms of flow, we can consider lighting and material as separate stages. But there's more than one type of light and more than one type of material.

We can break lighting into separate types of light, which will require different code for each light type.

And the code for materials can be even more varied than the code for lights. We are going to use the new visible function type in Metal to help us work with our lighting and material functions.

Visible is a new function qualification attribute like vertex, fragment or kernel. We can use the visible attributes on function definitions, and when we use the visible attribute, we are declaring that we want to manipulate the function from the Metal API. We check if we can use the API to perform this manipulation with the device query.

With visible functions, we can consider our code as a flexible object that we can refer to. In this case, let's consider the code for our area lights. That code is an object that can exist outside of the kernel that represents our pipeline. The code can exist in another Metal file or another Metal library.

To declare our lighting function as visible, we add the visible attribute before the definition of the function.

This will allow us to create a Metal function object to represent the code in this function.

Our next step is to connect our Metal shader code to our pipeline so that we can call it. First, we wrap our area light code in a Metal function object. Then the new Metal function object can be added to the pipeline.

With the visible attribute on our area light function, we can wrap it in a Metal function object on the CPU.

We create a Metal function object by name for our visible function using the standard methods.

We then add the function object to the compute pipeline descriptor as part of the linkedFunctions to allow the pipeline creation process to add it to the pipeline so that we can refer to it later with a function pointer. Now that we're talking about adding visible functions to our pipelines, we need to discuss the compilation model choices that we have available.

Once we have Metal function objects for each of our lighting and material functions, we can add them to our pipeline.

When we build our pipeline, we can take a copy of each of those visible functions. We call this "single compilation," since we then have a single object that represents our pipeline and all of the visible functions that it uses.

We use the same linkedFunctions object that we saw earlier to list the functions that we may call from our pipeline. Then we create our ComputePipelineState using the standard pipeline creation API.

The creation of our pipeline results in an object that contains both a specialized version of our kernel code and specialized copies of all of our functions. This specialization is similar to link-time optimization, where the kernel code and the visible functions can be optimized based on their usage.

However, this optimization can increase the time taken to create our pipeline and results in a larger pipeline object due to the copies of the function objects that we add into the pipeline. But what we may want to do is have our function objects outside of our pipeline as separate objects that our pipeline can call but does not have to copy. This is the foundation of a separately compiled pipeline.

When we create each Metal function object, we can compile each function to a stand-alone GPU binary form so that we can keep the function code separate and reuse it across multiple pipelines.

To compile our functions to binary, we will use a function descriptor. This allows us to add options to the creation of a Metal function object. In the case of creating our function, this snippet of code creates the same resulting Metal function as the same method with a name parameter. However, the functionDescriptor lets us specify more configuration options.

We request binary precompilation by using the "options" property of the descriptor. The function creation will now precompile our function to binary.

We then provide our new function in the binary function's array of the linkedFunctions object. This indicates that we are referring to the binary version of the function rather than requesting copying and specialization of the function for the compute pipeline. As you can see, we can mix and match precompiled functions with those we want specialized. And then we use the standard call to create the pipeline, as before.

Now that we have covered both single and separate compilation, this is a good point to compare the advantages of each.

For single compilation, we create visible functions using our standard methods. For separate compilation, we will precompile to binary to allow us to share the compile binary and avoid the binary compilation of our function during pipeline creation.

When we configure our pipeline descriptor, we use the functions array to indicate that we want them specialized and the binaryFunctions array to indicate that we want to use the binary versions.

The result of specialization is a larger pipeline in the single-compilation case. Separate compilation will result in a pipeline that adds calls to binary functions, and the binary functions will be shared.

Specialization of functions also requires a longer pipeline creation time than adding calls to binary functions. As I mentioned earlier, this is similar to link-time optimization, where the compiler can take advantage of knowing the whole pipeline but requires extra build time to apply the specializations.

All of that function specialization means that single compilation has the best runtime performance. The flexibility of the separately compiled pipeline means that there is some runtime overhead to calling our binary functions. As we saw earlier, you can mix sets of precompiled functions and functions for specialization, but a fully specialized, single-compilation pipeline will offer the best performance. It should always be possible to create a new single-compilation pipeline in the background to replace any separately compiled functions in an existing pipeline.

Going back to our separate compilation pipeline, we have our array of functions available to call from the pipeline. However, whenever you think you have a fixed set of functions, another function always appears.

In this case, we have a new wood material that we want to add to our pipeline. Incremental compilation is intended for adding new functions to an existing pipeline. The appearance of new functions is typically quite common in dynamic environments, especially games where streaming may load new assets with new shaders.

Putting this into code, first we need to make the choice to support incremental compilation when we create our initial compute pipeline. The default is to not support incremental compilation because enabling the later addition of binary functions means that pipeline creation has to expect possible calls to binary functions even if none are specified at pipeline creation time.

We then use a function descriptor to create the Metal function object for our wood shader as a precompiled binary function.

Finally, we use a newly added method on ComputePipelineState to create a compute pipeline with any additional binary functions.

Next, I want to talk about visible function tables. Visible function tables are how we pass function pointers to our visible functions to the GPU.

Going back to the set of the lighting and material functions that we considered for our shading, we need to provide these to the kernel running on the GPU.

To allow us to group our related functions together and pass them to the GPU, we create visible function tables using the Metal API.

Visible function tables are then an object that we can pass to our Metal shader code.

Before we start, let's add some using declarations to define our function pointer types to avoid making our code examples too wordy.

Visible function tables can be specified as kernel parameters, and they use buffer binding points. We can also pass them in argument buffers.

Then, in our shaders, we access our functions by index. We can take a pointer to the function or call it directly from the table.

On the CPU, we allocate the visible function tables from the ComputePipelineState based on the number of function entries we want in the table.

We then populate the table with handles to the functions that we specified when creating the pipeline state.

Finally, when we come to use the table, we set it on our computeCommandEncoder or argumentEncoder as required. Don't forget to call useResource if using an argumentEncoder. To ensure that using incrementally compiled pipelines is as low-cost as possible, we ensure that you can reuse the visible function tables from the ancestor pipelines. The handles that are already in the table are still valid, and you just need to add the new function handles to the table. You do not need to create and build an entirely new table. And finally, you just need to make sure that you do not access the newly added function handles from older pipelines.

Last but not least today, I want to discuss the performance considerations of using function pointers in your application. There's three main areas we will cover in performance. Let's start with function groups for optimization.

Going back to our earlier diagram, we could already see that we had groups of functions for specific purposes. However, pipeline creation is unaware of these relationships.

We can group the functions based upon their use in the shader. We know which functions we will be using for lighting and which we will use for materials.

To express the grouping of functions in our shading function, we've updated it to include function groups for the calls we make. In Metal, function groups let us tell the compiler where the functions will be used.

In our shader code, we apply function groups attributes to the lines where we invoke our functions to give names to the group of possible functions that are callable from that location.

Then, when configuring our compute pipeline descriptor, we specify the groups in a dictionary with the setter functions that may be called for each group. This gives the compiler the maximum amount of information possible and can help with the optimization when generating the pipeline.

On top of the specialization that the compiler performs for functions in our functions array, the compiler is able to take advantage of any commonalities between the setter functions in each group and then apply that to the call site marked with the function groups attribute.

All this new flexibility also means that you can now implement recursive functions.

If we go back to where we started with the ray tracing process flow, this model of ray tracing, where we consider multiple bounces, can be implemented in either an iterative or recursive manner.

If we focus on the relationship between intersection and shading, we can follow this call graph.

With our recursive path tracer, after an intersection, we shade the intersection point.

In this case, we hit our new wood material function. This wood material includes a reflection component, and so it intersects another ray with the scene and shades the intersection.

Again, we intersect a surface covered in the wood material. This then reflects and intersects the scene again. We hit the wood material one more time. We could continue, but typically you would limit the depth in a recursive ray tracer for both performance and to avoid overflowing the stack, so we will stop here. To support the varying stack usage for compute kernels that call chains of visible functions, we expose the maxCallStackDepth property on the compute pipeline descriptor so that we can specify how deep we expect to call functions from our kernel. The default is 1 so that the typical use cases of visible functions and intersection functions work out of the box. This value is expected to be used for any chains of visible function calls, but in the case of ray tracing, this code could have been written in an iterative manner to reduce stack usage. The last performance consideration I want to discuss today was the impact of divergence when we use function pointers. Before diving into function pointers, though, I should highlight that last year's "Ray Tracing with Metal" presentation covered high-level methods to handle the divergence inherent in ray tracing when subsequent bounces become less coherent. This included ray coherency with block linear layout, ray compaction for active rays and interleaved tiling for load balancing across GPUs. I recommend reviewing that presentation for a great review of ideas of ray tracing optimizations.

For function pointers, however, we need to consider divergence at the thread level. When we dispatch our threadgroups, we know that they execute in smaller groups of threads, defined as a SIMD group. In this example, we have eight SIMD groups.

The threads in the SIMD group perform best when they execute the same instruction at the same time.

Divergence occurs when the next instruction to execute is different for the threads of the SIMD group, typically, when they reach a branch in our shader code. This is normally handled by letting a subset of the threads execute their instruction while the other threads are left unused. We have the best performance when all threads are actively executing useful instructions.

Function pointers are another case that can lead to divergence. When we invoke a function via a function pointer, we need to consider how divergent the setter function pointers will be. In the worst case, within a SIMD group, each thread could be calling a different function, and the execution time will be the time to execute each of the required functions one after the other.

But if we consider the entire threadgroup, we may have enough work to create full SIMD groups.

To handle our divergence, we are going to reorder the function calls to introduce coherence to our SIMD groups. This means that the function call for one thread will likely be executed by another thread in the threadgroup.

In terms of code, we will start by writing all the function parameters and the index of the thread and the function to call to threadgroup memory. We will then use our favorite sort to sort a function indices.

Next, we invoke the functions in their sorted order.

The results of the functions go back to threadgroup memory, and then each thread can read its result from there. We can also implement a similar version using device memory for our parameters and results. In the case of calling complex functions, this should reduce the overhead of divergence. There's a lot of great things you can do with function pointers in Metal. Today we've covered the creation and use of visible functions and how we add them to visible function tables to provide functions that we can call from our compute kernels.

We've discussed the different compilation models that allow you to choose how you balance pipeline size and creation time against runtime performance and needing to be able to dynamically add functions. And we finished on some performance considerations for using function pointers in your application. I've really enjoyed working on function pointers this year, and I'm really glad to be able to share it with you. I hope you've had a great WWDC.

-

-

3:09 - Our simple Path Tracer in Metal Shading Language:

float3 shade(...); [[kernel]] void rtKernel(... device Material *materials, constant Light &light) { // ... device Material &material = materials[intersection.geometry_id]; float3 result = shade(ray, triangleIntersectionData, material, light); // ... } -

3:30 - Our shading function

float3 shade(...) { Lighting lighting = LightingFromLight(light, triangleIntersectionData); return CalculateLightingForMaterial(material, lighting, triangleIntersectionData); } -

4:59 - Declare a function as visible

[[visible]] Lighting Area(Light light, TriangleIntersectionData triangleIntersectionData) { Lighting result; // Clever math code ... return result; } -

5:30 - Single compilation pipeline on CPU

// Single compilation configuration let linkedFunctions = MTLLinkedFunctions() linkedFunctions.functions = [area, spot, sphere, hair, glass, skin] computeDescriptor.linkedFunctions = linkedFunctions // Pipeline creation let pipeline = try device.makeComputePipelineState(descriptor: computeDescriptor, options: [], reflection: nil) -

7:43 - Introducing MTLFunctionDescriptor

// Create by function descriptor: let functionDescriptor = MTLFunctionDescriptor() functionDescriptor.name = "Area" // More configuration goes here let areaBinaryFunction = try library.makeFunction(descriptor: functionDescriptor) -

8:08 - Binary pre–compilation

// Create and compile by function descriptor: let functionDescriptor = MTLFunctionDescriptor() functionDescriptor.name = "Area" functionDescriptor.options = MTLFunctionOptions.compileToBinary let areaBinaryFunction = try library.makeFunction(descriptor: functionDescriptor) -

8:20 - Binary functions

// Specify binary functions on compute pipeline descriptor let linkedFunctions = MTLLinkedFunctions() linkedFunctions.functions = [spot, sphere, hair, glass, skin] linkedFunctions.binaryFunctions = [areaBinaryFunction] computeDescriptor.linkedFunctions = linkedFunctions // Pipeline creation let pipeline = try device.makeComputePipelineState(descriptor: computeDescriptor, options: [], reflection: nil) -

11:04 - Incremental compilation pipeline

// Create initial pipeline with option computeDescriptor.supportAddingBinaryFunctions = true // Create and compile by function descriptor let functionDescriptor = MTLFunctionDescriptor() functionDescriptor.name = "Wood" functionDescriptor.options = MTLFunctionOptions.compileToBinary let wood = try library.makeFunction(descriptor: functionDescriptor) // Create new pipeline from existing pipeline let newPipeline = try pipeline.makeComputePipelineStateWithAdditionalBinaryFunctions(functions: [wood]) -

12:22 - Visible function tables on the GPU

// Helper using declaration in Metal using LightingFunction = Lighting(Light, TriangleIntersectionData); using MaterialFunction = float3(Material, Lighting, TriangleIntersectionData); // Specify tables as kernel parameters visible_function_table<LightingFunction> lightingFunctions [[buffer(1)]], visible_function_table<MaterialFunction> materialFunctions [[buffer(2)]], // Access via index LightingFunction *lightingFunction = lightingFunctions[light.index]; Lighting lighting = lightingFunction(light, triangleIntersection); return materialFunctions[material.index](material, lighting, triangleIntersection); -

12:49 - Visible function tables on the CPU

// Initialize descriptor let vftDescriptor = MTLVisibleFunctionTableDescriptor() vftDescriptor.functionCount = 3 let lightingFunctionTable = pipeline.makeVisibleFunctionTable(descriptor: vftDescriptor)! // Find and set functions by handle let functionHandle = pipeline.functionHandle(function: spot)! lightingFunctionTable.setFunction(functionHandle, index:0) // Find and set functions by handle computeCommandEncoder.setVisibleFunctionTable(lightingFunctionTable, bufferIndex:1) argumentEncoder.setVisibleFunctionTable(lightingFunctionTable, index:1) -

14:23 - Function groups on GPU

// Add function groups to our shading function float3 shade(...) { LightingFunction *lightingFunction = lightingFunctions[light.index]; [[function_groups("lighting")]] Lighting lighting = lightingFunction(light, triangleIntersection); MaterialFunction *materialFunction = materialFunctions[material.index]; [[function_groups("material")]] float3 result = materialFunction(material, lighting, triangleIntersection); return result; } -

14:49 - Function groups on CPU

// Function Group configuration let linkedFunctions = MTLLinkedFunctions() linkedFunctions.functions = [area, spot, sphere, hair, glass, skin] linkedFunctions.groups = ["lighting" : [area, spot, sphere ], "material" : [hair, glass, skin ] ] computeDescriptor.linkedFunctions = linkedFunctions

-