-

了解 Swift 中的数值计算

认识 Swift Numerics:一种用于计算数学的新 Swift 软件包。浏览软件包中可用的协议和类型,并了解如何使用它们编写通用代码。我们还将向你展示如何使用以及何时使用新的 Float16 类型来提高性能并减少内存使用。为了充分利用本次会议,你需要熟悉数学,例如对数函数,实数和虚数。你还应该熟悉 Swift 中的通用编程。

请观看 WWDC 18 中的“ Swift Generics(Expanded)”获得更多相关信息。资源

相关视频

WWDC21

WWDC20

-

搜索此视频…

Hello and welcome to WWDC. Hello and welcome to "Explore Numerical Computing in Swift." My name is Tim Kientzle. I'm with the Swift Runtime team and I'd like to talk to you about recent improvements to floating-point numerics support in Swift. I'll start by introducing the Swift Numerics package. Among other features, this package includes a protocol called "Real" and a fully functional Complex number type. Then I'll describe the new high performance Float16 type that we've added to the Swift core language and standard libraries. Let's start, by looking at the Numerics Package as a whole. The Swift Numerics package is an open-source Swift development effort hosted on github.com. It's designed to make it easy to implement numeric algorithms that work with any standard floating-point type. It does this by making the standard floating-point types usable with Swift's generic programming facilities.

To see how this works, let's assume you're working on some project where you discover you need to use the common "logit" or "log-odds" function from probability theory. You start by defining a 'logit' function that takes and returns a Double. To implement this function, you import the "log" and "log1p" functions from the Darwin module. This code works, but there's one small wrinkle.

This is written to only support Double. Someday you might want to use it with Float or maybe Float80. With a one-liner like this, it's no big deal to just make another copy of it. But, what if a new floating-point type gets added in the future? How do you handle types like Float80 that are only available on certain platforms? And of course, if this function were hundreds of lines, then duplication would create problems. Someone might correct a bug in one copy but fail to correctly edit the other copy.

This could get to be quite a mess. So let's instead try to define 'logit' as a generic function that can work with any floating-point type. Here's a reasonable first attempt. Unfortunately, this won't compile. The problem is that we've told the compiler that this function works for any type.

But of course the "log" and "log1p" functions aren't defined for every type. They only make sense for a handful of floating-point types. So we need some way to constrain the type T to only the types that are actual floating-point types with actual log functions available. Instead, let's import the Numerics module. By importing the Numerics module, we get access to the Real protocol which provides all the necessary support for this kind of programming. Using that, we can define our 'logit' function so it works for any fully functional floating-point type. We also need to use the generic forms of 'log' and 'log(onePlus:)' that are exposed by the Numerics module.

This implementation of 'logit' works for every standard floating-point type. If new floating-point types get added in the future, this code will support them without requiring any changes. This even works for Float80 on the platforms that support Float80 without you having to figure out the magic conditionals.

The key to this is the Real protocol. Let's take a closer look at that.

Types that conform to the Real protocol support all the standard floating-point capabilities. Real does this by combining several other protocols, as you can see in the definition here. This definition, by the way, is exactly the one that you can see in the Numerics source code.

The FloatingPoint protocol from the standard library is one key component here.

Two other protocols, AlgebraicField and RealFunctions, are new protocols defined by the Numerics package. But before I dive into details of those, I want to reiterate that the Real protocol is the one you should actually use. I'm going to describe how these other protocols fit together because I think it helps to better understand the range of capabilities that Real brings to the table. And, of course, if you ever need to define a new numeric type, you'll probably want to decompose your implementation along these lines. But for most of you, the Real protocol is the only one you will routinely work with. With that in mind, let's review the protocols that are already present in the Swift standard library. The Swift standard library defines a lot of protocols that apply to the standard floating-point types. This diagram shows just a few of the more important ones. For this talk, I'm only interested in three of these: AdditiveArithmetic, SignedNumeric and FloatingPoint. AdditiveArithmetic applies to types that support addition and subtraction. This covers almost anything that can reasonably claim to be some form of "number" and corresponds nicely to what mathematicians refer to as an "Algebraic Group." SignedNumeric extends that, with the concept of multiplication. Finally, FloatingPoint adds various notions that are needed for any practical computer floating-point number implementation, including comparison functions, a way to decompose numbers into exponent and significand, as well as useful constants like the largest and smallest value, infinity, pi and so on. The Numerics Package builds on these core concepts. The first protocol here augments SignedNumeric with a notion of division. Mathematicians refer to number systems that support all four basic operations as "algebraic fields," which inspired the name.

The ElementaryFunctions protocol specifies a large collection of common floating-point functions, including core trig functions as well as logarithms, exponentials, roots and powers.

The RealFunctions protocol extends this even further with many less used functions such as gamma and error functions as well as variations of the common trig functions.

The Real protocol combines all of these into a single unifying concept that neatly defines the common capabilities of the standard floating-point types.

Any type that conforms to the Real protocol is a floating-point type that supports all the standard arithmetic operations. And has a full repertoire of common mathematical functions. Which is how the Numerics package makes the standard floating-point types more usable than ever. Fundamentally, the Real protocol is a simple concept that is very powerful in practice. It lets you use generic programming techniques to define your floating-point code in a way that automatically supports every standard floating-point type. And it's built on top of a set of interlocking protocols that should make it easy to define new numeric types. Now, let us turn to the Complex number support provided by the Numerics Package. The Complex type in the Swift Numerics package is a fully featured implementation of a standard complex number type. To use it, just import that Numerics package into your program.

Because the Complex type is generic over the Real protocol, it works for any floating-point type. In this example, the constants 1.0 and 2.0 default to Double, so 'z' here is a 'Complex'. As always, Swift infers the type for you so you generally can just omit the type annotation. The Complex number type is useful in itself, but it's also a great example of how the Real protocol enables generic numeric programming. The basic type is defined a lot like this.

A complex number has both real and imaginary components and a way to create new complex numbers from those components. Those components can be any NumberType that conforms to the Real protocol. To make complex numbers fully functional, of course, we need to define the standard arithmetic operations.

Here are the basic addition, subtraction, and multiplication operations as required by the SignedNumeric protocol we discussed a little while ago. Complex numbers are often expressed in polar coordinates. That is, in terms of a length and a phase angle. Because the real and imaginary components are floating-point types that conform to the Real protocol, we automatically get everything we need to expose those length and phase properties. The length is defined in terms of the standard hypotenuse function, the phase in terms of the standard arctangent function. Other common trig functions let us create new complex numbers with a specified length and phase. This complex type is a plain struct holding two floating-point values. As a result, its memory layout precisely matches that of the C and C++ complex number types. So complex numbers in memory look exactly the same in all three languages. You can create a buffer full of complex numbers in Swift and pass a pointer to that buffer to a C or C++ library that expects the corresponding C or C++ complex type. To see how this works, let's look at an example using Accelerate's implementation of the Basic Linear Algebra Subroutines. The first part of this example just creates an array of 100 Complex values using a common Swift idiom. Now we can use the ampersand operator to pass a pointer to this array directly into the Accelerate API.

This particular function accepts an array of Complexs, computes the Euclidean 2-norm and returns a Double. Especially when porting code from C or C++, you may need to be careful when dealing with infinity or NaN values. There have been different styles over the years for how these should work. It's not surprising that C and C++ use the same style as each other. After all, their complex number support was standardized at about the same time.

Swift, however, uses a slightly different convention that is simpler and significantly more performant. To see the difference, here's a basic benchmark program that just performs a bunch of complex multiplications and divisions.

With this program, multiplication is about 1.3 times faster in Swift than in C. Division is almost 4 times faster. And, if you can arrange your work so that you're dividing by a constant, then you'll find that division in Swift can be over 10 times faster. I hope the previous sections have given you a taste of what we're trying to accomplish with the Swift Numerics package. This is a work in progress. The package is being developed as a community effort on GitHub and there are active discussions about where to take it in the future. New features are added regularly. This has recently included improved handling of integer powers and some new tools for dealing with approximate equality. There are also active discussions about how to extend the library with support for arbitrary precision integers, shaped arrays and decimal floating-point. If you would like to participate, please check out the project on github.com or join the discussion in the Swift forums. Now, let's turn to the core Swift Language and standard library and the new Float16 data type. Float16 is an IEEE 754 standard floating-point format that is new to Swift. It's already available in Swift on ARM-based platforms and we're working with Intel to finalize the correct calling convention before we landed this on x86. Float16 is in every way a standard and fully supported floating-point type. It conforms to the core protocols from the standard library, including things like SIMDScalar. It conforms to the Real protocol that I discussed earlier in this talk. As you recall, this means that it supports all of the standard floating-point operations and functions. So our earlier diagram that shows the types that conform to Real now has a fourth type. In the months since Swift Numerics was released, there are already a number of projects using the Real protocol to write algorithms that work across all standard floating-point types. Without any source code changes at all, those projects already work with Float16. Like any actual numeric format, there are tradeoffs to using Float16 instead of some other type. Most of those tradeoffs relate simply to its size. Since it's a smaller data type, you can fit more of them in a SIMD register or in a page of memory, which directly translates into improved performance. However, as a smaller data type, it also has a more limited precision and range. Let's take a careful look at that. As the name suggests, a Float16 takes just 16 bits or 2 bytes as opposed to 4 bytes for a single precision Float or 8 bytes for a double-precision value.

The smallest value it can represent is around 10 to the minus 8, which is generally not a concern. However, the maximum value that a Float16 can represent is just a little more than 65,000. This can be a problem for many applications and it's something you should be careful with when translating code that was originally implemented for Double or Float to work with Float16.

On the hardware side, Float16 is already well supported. Apple GPUs have used this for a long time and Apple CPUs have direct support beginning with A11 Bionic. On older CPUs, we support Float16 by simulating the operations using Float. The results are exactly the same, only a little slower.

As I mentioned before, on hardware that does fully support Float16, you can fit twice as many values into the same SIMD registers, which generally translates into a doubling of performance. To see how that plays out in practice, let's look at a simple benchmark that compares a BNNS convolution computed in single-precision Float, where we get about 49 giga-flops to one computed with Float16 which achieves 119 giga-flops, even more than twice the performance.

This talk has discussed the Swift Numerics package and shown how the Real protocol provides a way to write floating-point algorithms generically so they work with all floating-point types. I've also talked about a new complex type that provides full interoperability with C and C++ and finally, I've introduced the new Float16 type that improves our support for high performance numerics. To get involved, you can visit the Swift Numerics project on GitHub, take a look at the existing issues and Pull Requests to understand what work is ongoing and contribute your own ideas to the group.

You can also visit the Swift forums at forums.swift.org and look in the "Related Projects" Category to find discussion specifically about Swift Numerics.

I appreciate you joining me for this look at Swift Numerics and I hope you enjoy the conference!

-

-

1:05 - The log-odds function (Double)

import Darwin /// The log-odds function /// /// https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Logit /// /// - Parameter p: /// A probability in the range 0...1. /// /// - Returns: /// The log of the odds, 'log(p/(1-p))'. func logit(_ p: Double) -> Double { log(p) - log1p(-p) } -

2:33 - The log-odds function (Real)

import Numerics /// The log-odds function /// /// https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Logit /// /// - Parameter p: /// A probability in the range 0...1. /// /// - Returns: /// The log of the odds, 'log(p/(1-p))'. func logit<NumberType: Real>(_ p: NumberType) -> NumberType { .log(p) - .log(onePlus: -p) } -

7:10 - The Complex type

import Numerics let z = Complex(1.0, 2.0) // z = 1 + 2 i -

7:38 - The Complex type: Basic definition

public struct Complex<NumberType> where NumberType: Real { /// The real component public var real: NumberType /// The imaginary component public var imaginary: NumberType /// Construct a complex number with specified real and imaginary parts public init(_ real: NumberType, _ imaginary: NumberType) { self.real = real self.imaginary = imaginary } } -

8:04 - The Complex type: Standard arithmetic operations

extension Complex: SignedNumeric { /// The sum of 'z' and 'w' public static func +(z: Complex, w: Complex) -> Complex { return Complex(z.real + w.real, z.imaginary + w.imaginary) } /// The difference of 'z' and 'w' public static func -(z: Complex, w: Complex) -> Complex { return Complex(z.real - w.real, z.imaginary - w.imaginary) } /// The product of 'z' and 'w' public static func *(z: Complex, w: Complex) -> Complex { return Complex(z.real * w.real - z.imaginary * w.imaginary, z.real * w.imaginary + z.imaginary * w.real) } } -

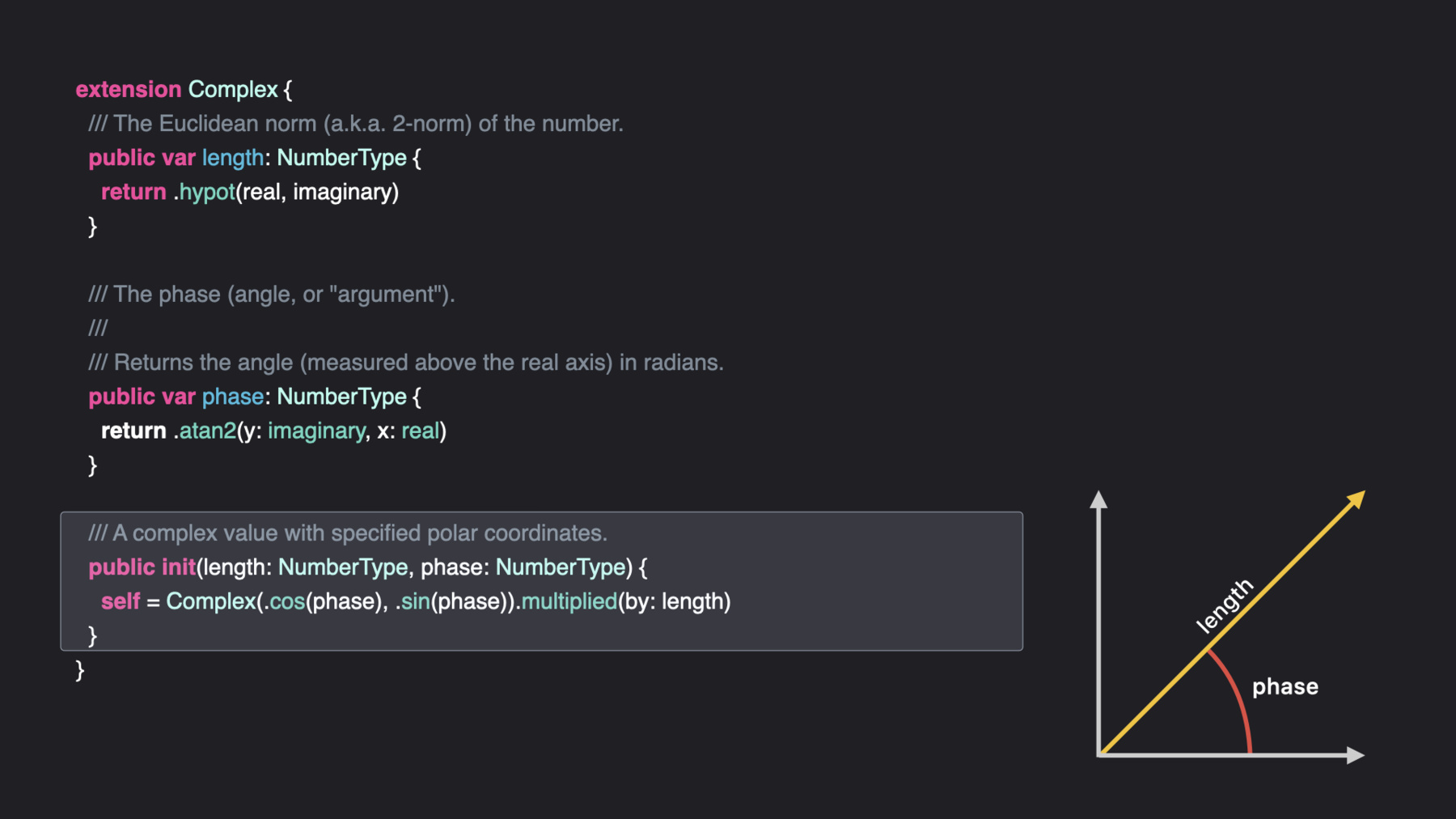

8:19 - The Complex type: Polar coordinates

extension Complex { /// The Euclidean norm (a.k.a. 2-norm) of the number. public var length: NumberType { return .hypot(real, imaginary) } /// The phase (angle, or "argument"). /// /// Returns the angle (measured above the real axis) in radians. public var phase: NumberType { return .atan2(y: imaginary, x: real) } /// A complex value with specified polar coordinates. public init(length: NumberType, phase: NumberType) { self = Complex(.cos(phase), .sin(phase)).multiplied(by: length) } } -

9:16 - Using Accelerate's Basic Linear Algebra Subroutines

import Numerics import Accelerate /// Array of 100 random Complex<Double> numbers let z = (0 ..< 100).map { Complex(length: 1.0, phase: Double.random(in: -.pi ... .pi)) } /// Compute the Euclidean norm of z let norm = cblas_dznrm2(z.count, &z, 1)

-