-

Intentional Design

Great app experiences leap off the screen. They are dynamic, immersive, personal, and, above all else, the result of a strong and clear intent. Learn key techniques for being intentional with your design by choosing appropriate metaphors, making extreme choices, and making every interaction feel more authentic and natural.

리소스

-

비디오 검색…

So hello everyone. My name is Doug LeMoine. My background is in interaction design. And here at Apple I'm on a team of people who works with developers like you. As a designer I focus on user interfaces and the ideas to deliver great user experiences to the people who use your apps.

Today I'm here to talk about intent.

I think there's a thread running through great apps and really great products. And it has to do with a conscious focus on people, on humans, and what they want and what they really need.

So I'm going to talk about focusing on the person you want to serve. And I'm going to focus on being intentional. The intent that I'm interested in talking about today is less about a specific design vision or a specific outcome and more on a mindset. How to keep a sharp focus on those people that you're trying to reach and create apps that feel simple. And when an app feels simple users perceive it as natural, an extension of what they know. It feels like it arises from their experience and it flows naturally from what they expect.

So I know simple and natural are sort of designer cliches, we say this stuff all the time. Like, what do we mean? I think these terms are shorthand for discussing qualities of apps that create feelings of comfort and confidence.

When people feel comfortable and confident, when we understand how a thing works, we can move through it seamlessly without needed to learn or figure it out. So intent is the kind of thing is hard to define but you know it when you see it.

So I'm going to show you some examples of apps that I found in the last year that really deliver real value to people and really connect with them.

And I'm going to talk about five elements of intentional design that we can learn from these apps and that you can apply to your work.

So let's dive in.

So before mobile devices came around when you traveled abroad you'd carry a paper map.

And the advantage of the paper map is that when you would approach a local they would instantly recognize what kind of help you needed.

So mobile maps have made people more independent, right? We probably approach fewer locals when we're traveling abroad.

But in the same way that a paper map invites an interaction, there's an app called iTranslate Converse that makes it easy to approach a local with your iPhone in your hand to ask a question or get directions. Some of you may have seen this on Monday night at the Apple Design Awards. I'm going to go through a demo to really bring out what I think is really intentional about this app.

So first of all there's very little UI. The screen is essentially one big button. I tap and hold and start talking. So I'll show you that in a second. And to be clear the goal of iTranslate Converse is to make conversation easy. The developers have intended this app to be used together. So two people together, one of whom most likely has never used this app before, probably never even seen it. So I launched this app really for real in in the Naples train station when I was trying to get on an express train to Rome and the platforms were really confusing. So I pulled out my phone, I launched the app, and I walked up to a conductor. So I said is this the express train to Rome? The app translated it into Italian and the conductor heard.

Then I could flip the phone around and again, what I find interesting in this situation that other person has probably never seen this app before. And they speak in a language that I didn't speak but the app is smart enough to know that it's ether going to English or Italian to listen for.

So the conductor spoke into the microphone.

Platform Nine. And the app translates it for me. So in reality he spoke English.

But he did want to see how the app worked and I showed him and he was impressed. I think the real beauty of this is that you can make a connection with a person, right? You can get on the right train like I did, but you also make a human connection in the process. So the developer's intent here is to enable communication between two people in real time. Just touch the screen and talk. So the first element of intentional design is what I'm going to call radical simplification.

So how did they do this? Well, I think they considered the context really well, the context that this will be used in.

They took into account where and when people would pull out their phone and launch their app. You're probably in a foreign country, like this guy you're jetlagged, lost, tired, your hair is uncombed, your jacket is rumpled.

I'm not even sure if that's a map that he's carrying at this moment, it kind of looks like a book.

So they remove the UI and allow people to focus on what they need, which is to find something, to ask a question, to get their bearings.

And it's amazing how much an experience can change when actions are removed from the UI. So I want to show you another example.

This is an app called Vanido. It helps you learn how to sing.

So if you're the kind of person who wants to learn how to sing with literally no one hearing your or judging you, this app is amazing.

This is the UI.

It's so simple. The app tracks the pitch of my voice while I'm singing and it's continually giving me feedback. Am I hitting my notes or not? So let me show you. I'm actually not going to do a live demo. But I am going to sing along because I've been practicing and I want you to see how it works.

You can leave feedback in my session. So what I love about Vanido is that it has stripped away what music education looks like, right? There's no charts or notes. It's colorful, it's animated, and it's fun.

And you should have heard me sing before I started using this app. It really works. And there's only one interactive element on the screen when you're singing and it's way up at the top left.

So you can hold your phone like a microphone and really belt it out without worrying about accidentally exiting your lesson.

So this is radical simplification and that's what I mean, that's the first manifestation of intent and intentional design.

Being radical means taking risks, right? Removing a bunch of stuff from the UI could be jarring if you don't do it right. But I think there's a way to reduce your risk. So next I want to talk about people and about orienting your design around what people really want. So what do they want? I think this is worth exploring because it's almost never obvious.

The first needs that you see when you start kind of looking at people and the users that you might want to serve are superficial and you need to dig past those. They might be the first ones that you think about addressing or they might be the ones that pulled you into the problem in the first place, but you need to keep digging because those superficial needs often mask deeper needs, right, you could solve them but not really solve the persons' problem. So you have to keep digging. The second element of intentional design that I want to get into here is called deep understanding. So knowing the person that you want to reach and the actually problem that they have.

The deeper you dig the more likely you are to see where the real opportunity to meet their needs is. And the app that really shows this off, in my opinion, is called Streaks Workout.

So it's a workout app but I want to go behind the scenes a little bit.

On the surface it looks like many workout apps. It guides your workouts. This is the primary screen and it looks pretty simple. You pick a workout duration and you go. But personally, I'll confess that I don't love working out and I've tried many workout apps that I just don't stick with and I want to thank any developers that are here who have developed workout apps that I've tried because I respect your effort and I'm really trying to get fit so thank you for that. But what I struggle with is staying motivated. It's easy to get bored or burnt out and this isn't an unknown problem, right? Many people feel this sense of inertia when facing something challenging like a workout.

So inertia, just to be clear, is a disinclination to move. And that's what I feel. I feel a sense of disinclination when I think about working out.

So I want to walk you through how Streaks Workout helps users handle this. So when you first launch the app you select movements that you want to do, these exercise movements on a screen like this. And there's dozens of these things. You can scroll down and pick as many as you want.

After that when you want to start a workout there's just one tap. You just pick a duration and you go. And the app does the rest. It auto selects from your movements and it picks a sequence and then you're in the workout.

You guys psyched up? So let's fast forward a bit. Now I'm doing ten seconds of crunches. Crunches ten seconds.

I'm actually not going to do the crunches. But as you can see I can't see what's next, right? The question mark means it's random. It's a surprise.

Burpees ten seconds. Yeah, I'm not going to do those either.

Specifically, what I think works well is that the app confronts the inertia that people might feel by introducing a sense of randomness and removing work.

So the developers recognize that each step in the process of doing a workout requires a choice, requires someone to think about what they want and these decisions are not things that everyone wants to make.

So you only choose movements once. After that the app does it for you. And you never choose the sequence or the reps so half of the work, half of the potential inertia is gone.

You could say that Streaks workout -- it takes the work out -- Of workouts! Really bad.

They've taken half of the work out anyway.

So this launch sequence reveals the movements that you'll do and it helps each workout feel new.

Of course there are probably many of you in the audience that perceive that this app actually lacks essential features. Choosing reps is amazing. Picking a sequence isn't work.

If this is you I have great news. There are lots of apps that allow you to do those things. But I'm curious about what inspired this. Whenever I see something unique like this I wonder what's behind it because it's unique and it's implemented really well. So I asked the developers of Streaks Workout.

And it's such a common story to hear about how an app originated with an idea that came out of prison.

So specifically, their idea originated with how inmates in prison keep workouts new and interesting. So I want to walk you through how that works. So in prison you take a normal deck of cards and at the beginning of each workout you would assign a movement to each suit. So today diamonds are crunches.

The numbers on the cards represent the number of reps per movement. So at the beginning of the workout you'd put the deck face down and you'd start drawing and each card would deliver a movement and a rep count. OK, everyone eight crunches.

So the original app concept was a literal recreation of this. This is an early comp and they also prototyped shuffling and flipping cards to try to kind of replicate the origin of this prison workout. But they quickly moved past the literal approach.

They didn't stick to the literal deck of cards because it carried too many constraints. Four suits would limit the number of movements that you could do in each workout and people would somehow need to remember that diamonds represented crunches in that particular workout and that's work, right? So instead they focused on the value that they wanted to bring.

They wanted to help people make a habit of working out.

So they acknowledged that people felt inertia when they were going to launch a workout app and they removed as much as possible that might trigger that and they stayed true to the original intent of the prison workout, which is that spirit of randomness and surprise. And that's what I mean by deep understanding. Knowing the person that you want to reach and the actual problem that they might have. So the superficial approach to this workout would have been just a typical workout app, right? Of course people want to get healthy. But what people really want, or what I really want anyway is to get past the boredom and that inertia and they've addressed that for me.

So knowing users is nothing new. I'm guessing a lot of you here have personas and market segments and you do surveys and other kinds of user research focus groups. Maybe you create experience maps and customer journeys and user stories. All of those can be useful models.

But they have to feel authentic, right? They actually have to feel like people.

That can make focus easier and it can help teams kind of come together around a vision. As long as you share a common understanding and you feel a real empathy for the person that you're designing for. Those can work.

But too often those artifacts of needs and goals and skills, they just feel artificial.

They may not connect with everyone. They feel complicated or distant or corny. So for a moment I want to talk about how much easier it is to make some something when you really care about the person you're making it for.

So I first heard about this story that I'm going to tell you in a book. It's by a guy named Alan Cooper, he's a software developer from the early days, and his claim to fame is that he created a prototype that became Visual Basic. And this is an actual pixel resolution of Visual Basic 1.0 on a 4K display. It's pretty amazing.

So Alan built this with a small team and as he did it he began to recognize a problem in maintaining a focus on what people really want. And he tells this great story in a book about another invention and that story is a parable of how powerful knowing people can be, knowing the person that you're designing for. So apologies if I got your hopes up about Visual Basic. I'm actually not going to talk about that. I want to focus on this story and kind of extend it a little bit.

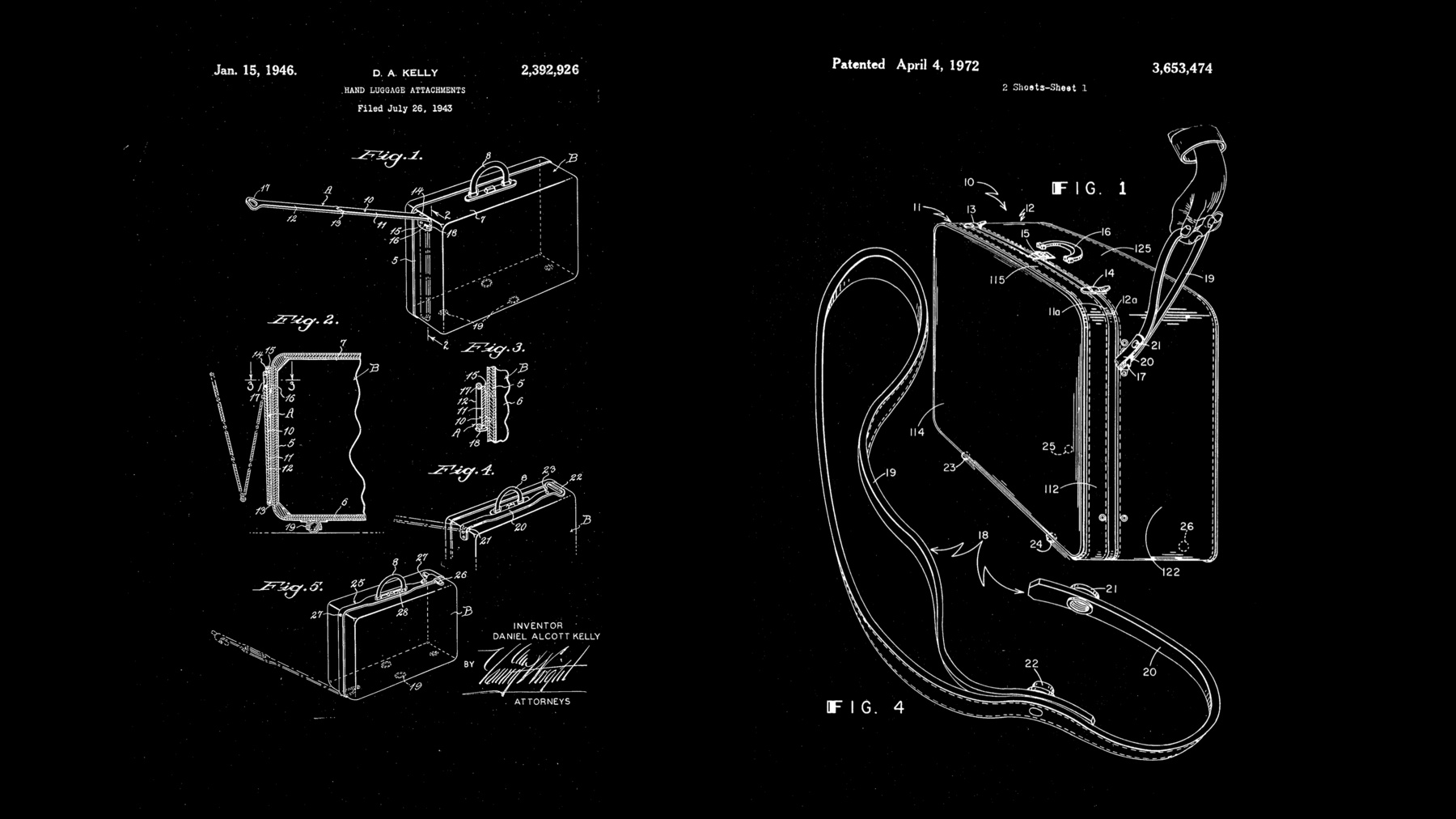

So the invention that he talks about is the Rollaboard Suitcase. So this is the patent form for the Rollaboard.

So nowadays the suitcase might seem pretty unremarkable.

For most of us this is just a suitcase, big deal.

But it actually hasn't been around for that long. The patent was filed in 1989. People have been traveling forever though. So why did it take so long to design something so obvious? The inventor was a guy named Robert Plath. I'm guessing not a household name, but more on that in a minute.

So what was innovative about this? Well, I think the innovations are subtle. It wasn't the wheels. Many patents had been filed for wheeled suitcases before. This is from the '70s. So the wheels are underneath and it's also got some kind of leash thing.

Suitcase manufactures had been trying to put wheels on suitcases as far back as the '40s and this actually has some kind of other leash thing, some grabber thing that you can see right there. So clearly people have been trying to figure out a way to not carry heavy things.

So if you worked in the luggage industry in 1989, you probably thought you'd already innovated.

You weren't worried about this new patent I'm guessing. But we all know what happened, right? The new design became the de facto design of suitcases. And the improvements in retrospect are totally obvious. There's a handle at the top so the whole suitcase it oriented to be upright. It's easy to grab and pull and pivot. That is the evolution of the leash.

Second the wheels, right? The wheels are placed on the edge so they're only fully engaged when the suitcase is tilted. And finally the size, it's small enough to lift and place in an overhead bin. So nothing particularly revolutionary but the inventor Robert Plath made each decision to serve a really specific person, a person who traveled for a living. Robert Plath was a pilot for Northwest Airlines. He intimately knew the pain of lugging and lifting heavy things. He did it every day.

And he deeply understood what people like him wanted, to move with ease while looking professional, and he made something perfectly suited for that.

So what I find really interesting is that at the times, 1989, there were only about 100,000 travel professionals as the Census Data called them, but pilots, flight attendants, people in the travel industry. That 100,000 might seem like a lot, but when you compare that number to the overall market of people who traveled a couple times a year, just like more than 100 million at the time, and that's just Census Data from the U.S., his target user, quote-unquote, was a really specific person that represented only 0.1% of 1% of the market.

So what I'm saying is that typical methods of market identification probably would not have led Robert Plath to focus so narrowly.

He focused on an extreme use case, a person who traveled all the time. So I'm using extreme intentionally to emphasize that he focused on what we might call an edge case. The market size was really small and his solution was kind of whacky. It looked really different. It implied a new kind of default way of interacting with your luggage.

So he focused on the needs of people he intimately knew and that extreme focus allowed the real needs of a lot of people to come to the surface. So his focus gave him the freedom to arrive at an extreme solution.

So the third element of intent is extreme focus. So what might seem like an edge case could be what frees you to reorient or refocus your design. Make it more coherent. Make it simpler. And therefore actually reach more people.

So let's relate extreme to our work. Is there a way to relate extreme to the work that we do? I think there is and I think being extreme can be really worthwhile but you have to nail it.

So you might not immediately associate the words extreme and weather app. But Carrot Weather is a really compelling illustration of being extreme.

So on the surface it's a weather app. So let's check the weather forecast.

I wonder how many licks it takes to get to the center of a human skull.

So right, they're not typical forecasts. The voice of Carrot, which is the robotic voice that you heard, has personality and attitude and a little bit of an edge. You probably think this sunshine means that things are starting to look up for you. They're not.

So you might ask is that even a forecast ? So sometimes when I read these things I just feel like it's being mean to me. It's definitely got an attitude but the key information is super readable and the screen is really nicely organized.

The color scheme changes according to the time of day and it's really playful. And it's got those illustrations along the bottom that are sometimes bizarre and often really funny.

So the forecast is only one of quite a few unique elements in the app. So I ask the developer whose name is Brian Mueller, to help me understand where this came from and he told me something interesting. He said that when we writes in the voice of Carrot, he's channeling the personalities of people really close to him -- his wife, his sister, and his mom. And these forecasts are a form of conversation with them. So the lesson is that the people that Brian is trying to reach, the people that he's speaking to with these forecasts are actually really specific. And I think that's what makes his apps stand out. The edginess helps him connect with people. And it's not surprising to me that he's had so much success in the app store.

The personal touch is what allows his app to deeply connect with the rest of us. Obviously personality isn't the sole province of weather apps. All apps can deliver something like this. All apps can feel handcrafted and special. And that's the fourth element of intent that I want to talk about. Intentionally designed apps feel personal. They create a personal connection.

So the point isn't to spice up your copy, right? The point is that spicy copy in the right context feels memorable.

And it must be said that the personality of Carrot is probably not for everyone.

And I talked with Brian he commented on this.

So you can probably imagine the email and Tweets that he gets from people who are surprised or upset or offended by the forecast after they download the app. Like, you know, how dare he insult meteorologists like this? So he offers an olive branch -- To these disgruntled souls. They can adjust the personality from the default, which as you saw was Homicidal. You could go the left for less edge and to the right for more. But the bottom line just to be clear is that edgy text would be less funny or perhaps not funny at all if the app didn't work, right? It's a good weather app with simple navigation and a playful UI.

The extreme personality though is what gives life and sprit to it. So when I get a Carrot notification it's similar to the feeling that I have when I go out to a local restaurant or bar where everyone knows my name, right? It's enjoyable, it's personal, and it's comfortable.

So we've got four things that characterize intent and the behavior of intentionally designed apps. And I want to flip things around for a moment and talk about what happens when you're not intentional. In other words, where does bad UI come from? So I think the best friends and the worst enemies to designing intentionally are all of the systems and patterns that we've internalized as we've gained experience in the work that we do.

This experience allows us to make decisions quickly and to be really efficient in that work.

But these familiar patterns get in the way of our ability to reckon with new problems. Sometimes we won't even recognize that the problems are new and this is true of anyone who has tried to make anything new ever, right? Suitcases once had a form. They were rectangular and the long side was down.

That form was adjusted but the fundamental elements were always taken as a given. The wheels were tacked on but the overall form stayed the same.

For decades smart people considered this form and stopped there. It took someone with a very sharp focus on an extreme audience to break out of this pattern, right, and turn the form on it's head .

Thank you. So we apply patterns automatically. Our brains make connections quickly and that has benefits, right? It helps us work efficiently. It helps us be consistent, but it also prevents us from noticing the obvious and challenging it, asking fundamental questions, why does this thing need to be this way? So as a UI designer it's really tempting always to draw on familiar UI elements to solve new problems. I'm sure you're familiar with the house icon. It made sense in a desktop browser. A browser is a frame for the Internet universe. A browser home button will lift you out of whatever corner of the dark web that you found yourself in and allows you to get out of there.

So that notion of home was extended to iPhone and the behavior is similar.

It's a shortcut, it's an easy button, home is a starting place, and unlike in real life, home is a place that you can always return to with a simple gesture.

You can go home whenever you want.

So home is also a familiar notion in the finder. Here the spirit is more like -- you followed the river to it's headwaters.

On the Mac, home represents a container. Everything is in here. You don't need to look anywhere else. you have reached the source.

Home in these contexts offers reliability, safety, an ability to return as you navigate outward. And it's clear obvious utility elsewhere on the platform might seem like a reasonable choice as a tab bar icon, right? Except there's a crucial difference in using the notion of home in a tab bar.

To be blunt, an app isn't a frame containing god knows what.

A typical app offers specific things, specific contents, specific tools, specific actions. And a tab bar is a quick expression of the overall utility of your app. It's a high-level map of your app. So let's use an example that's close to home -- the tab bar of WWDC app.

So we all can get a quick understanding of the scope of information that's available in the app simply by scanning the tab bar.

We can guess at what content might be in each tab. So tab bar icons and tab bar labels should be as direct as possible.

And this directness will then limit what each tab can contain and that's great.

Directness creates predictability. So the app may not do everything, right, no app does everything.

But people won't have to hunt around to figure out what it does and doesn't do.

So when I talk about home I'm talking about a metaphor, homeland, a home base.

So let's just dig in to why home doesn't work. First it's overly broad and it feels generic.

And I think it's a copout. You're avoiding a decision by naming a tab Home. The perceived comforts of home as an icon in a label are getting in the way of being direct, of clearly and directly communicating the scope of what's in your app. If your app is a meditation app and offers content related to meditating and building a meditation practice, imagine the impression that it would leave on people if not only the tab bar was more direct, but the directness of the tab bar enforced a simplicity and an order on the content that you display. And that content was predictable and directly organized.

So indirect labels feel conventional and they feel safe but they mask utility. Like a storage locker you're putting your valuable stuff behind a door that's anonymous and inscrutable. And this is what I mean by unintentional design.

No one intends to be indirect.

Being intentional will lead to cleaner and clearer communication. And this brings me to my final element of intent. Direct communication. Intentionally design things. Clearly communicate to the people who use them. And the way to achieve this is to draw on what people learn on the platform and in the world. So I want to show you a couple of last quick examples of apps that rely on a familiar form to make interactions feel useful.

So the core concept of an app called Tinycards is to bring flashcards on to a mobile advice. You can use them to memorize pretty much anything -- languages, flowers, leaves, almost anything. So the interaction within the app is super direct. People expect cards to have dimension, so that periodic pulse is inviting you to interact with the card.

You flip the card over by tapping it. So these cards have two sides.

They've respected the metaphor of the card.

People appreciate that. So the entire experience of Tinycards is based on quickly flicking through these cards as you commit things to memory. Like for instance the flags of Canadian provinces. Does anyone know this one? Ontario. Let's try it.

Oh my gosh.

You've done that quiz before, right? So the UI of Tinycards is so clear you don't even think about it. Working with cards feels completely natural and you can just focus on your goal, which is learning stuff.

So what Tinycards demonstrates to me is that if you implement a metaphor well, people will instantly become immersed. They'll forget that they're even interacting with a UI.

And once they're immersed, you even have the opportunity to extend the metaphor, to really surprise and even delight people.

So I want to show you a game. It's called Gorogoa and it extends the metaphor of the card in a way that I feel like creates a truly unique experience.

So Gorogoa is a puzzle game. You move cards around a grid and you advance in the game and in the story by getting them into the right positions. But you could see that these cards do things that no actual cards can do. They can be torn off and as you'll see in a moment they can actually stitch themselves together into a scene.

Yeah, this is an incredible game. And it's a great example of how you can extend the metaphor farther than you might think and create something truly amazing. This moment right here where you've got this card metaphor that suddenly kind of disappears, that's purely delightful and it's really I think a great testament to how well he's implemented the metaphor of cards.

Bending and extending metaphors doesn't work if the result doesn't extend the utility, or value, or delight of your app. That's why the home tab on the tab bar doesn't work, right? It doesn't extend the utility of the app or create any additional value.

So the last app I want to show you is an example that combines metaphors from the real and digital world in a really simple way. It's called Rosarium. Yeah.

I think the developers are here. It's a rosary that you wear on your wrist and I believe that is Latin and the font is really communicating to me that it's Latin anyway. So the beads are represented by circles. Each time you turn the digital crown you get a slight haptic tab. So when I met the developers they told me that they were inspired by the similarity between the feel of rotating the digital crown and the feel of an actual rosary bead. So the app has translated this real world object, just a strand of beads, into the virtual world in a way that feels really natural.

So I'm no suggesting that it's a replacement for rosary beads or any prayer beads because the physical beads can have deep, you know, personal meaning. But I love how they've thoughtfully carried that real world experience into a digital form in a way that's so radically simple and clear.

And I think it really illustrates each of the points that I made earlier -- the simplicity and the understanding of people, the extreme kind of focus on a problem and the direct communication of a solution. And this is intent in action. This is being intentional in design. It's a matter of turning off the automatic part of your brain, of slowing down, and challenging the obvious.

It requires a level of intention that will enable your decisions to become more conscious and for you to become aware of the patterns and the familiar things that might get in the way and block you and focus on people, right? The people that you want to serve, the person who inspires you, the family member who allows you to be the best version of yourself, the coworkers with whom you share a real need for something better, and you can take that inspiration and use it to discover newer and better ways to connect with people and to create something really great.

So you can check out more about my session here. Thank you very much. And please, please stick around for the next talk. The next talk is designing fluid interfaces. It's a great talk. Easily one of the top seven design talks at this year's WWDC. So thank you.

[ Applause ]

-