Behind the Design: Overboard!

September 12, 2022

The murder mystery game Overboard! is a whodunit with a killer twist: You done it… and now you have to get away with it.

In Overboard!, you play not as the detective but the murderer most foul — Veronica Villensey, a fading 1930s starlet who’s tossed her husband off a cruise ship. Now, you have just eight in-game hours to pin the crime on somebody else. Chat with unsuspecting (and suspecting) shipmates, eliminate problematic evidence, blackmail a spy, seduce a potential ally, show up to breakfast on time, cheat at a card game, visit a chapel (awkward), and lie — to everyone, basically all the time. (Did we mention the game won its 2022 Apple Design Award for “Delight and Fun”?)

To get away with the crime, you'll need to keep your story straight.

The upside-down narrative noir mystery is full of vintage style, stabs of dark humor, and a proper cast of murder-novel players: the fetching dame in the Lauren Bacall hat, the dashing ship commander, the crusty old woman with many axes to grind, and more. Made in just 100 pandemic days, it’s also a relatively breezy game that you can play in about 20 minutes — and then promptly replay to properly discover all of its multiple storylines and endings.

“We looked around and thought, ‘How has no one done Agatha Christie yet?’” says Jon Ingold, co-founder of game studio Inkle and the game’s author. But the magic is how Overboard! takes on Christie from the other side — while the Death on the Nile-inspired chess pieces seem familiar, the construct certainly isn’t. “I definitely had the most fun job here,” he says.

Generally you don’t see this type of behavior from non-guilty people.

The game's development came as a surprise — even to the studio itself. Inkle’s acclaimed portfolio includes titles like Sorcery!, Heaven’s Vault, and Jules Verne adventure 80 Days, and Ingold and studio co-founder Joe Humfrey had been heads down on their next release: a game set in the Scottish highlands. In December 2020, however, Ingold turned up with an idea about a golden-age throwback mystery — a palate-cleansing side hustle that could be hammered out quickly.

“When you’re working on a big project, you’re always dying to work on something smaller,” says Humfrey. “So we thought, let’s just do a one-month game jam! It’s not like it’ll destroy the other project! It ended up taking three months instead of one, but the attitude was refreshing. You don’t labor over your decisions, and you’re ruthless about coming up with elegant design.”

For Ingold, that speed became a delightful mechanic in of itself. “We had this bizarre constraint of trying to go as fast as we could,” laughs Ingold. “We kept saying, ‘This isn’t even what we’re supposed to be doing right now! We can’t let this get out of the box!’” Luckily, they had a studio full of tools that gave them a big head start.

Writing with Ink

Twelve years ago, Humfrey and Ingold left company jobs to launch their own game studio — and became accidental inventors in the process. “Inkle is a bit unusual in that we have a narrative engine that we built for ourselves,” Ingold says.

That proprietary engine, Ink, is essentially a word processor that lets Ingold and the Inkle team write a branching narrative story straight through — “like a film script,” Ingold says — before going back to flesh it out, expand the story, and sprinkle in all the choices, branches, and detours. “It’s like Markdown for interactive fiction,” says Humfrey.

Meet Clarissa, Anders, and Subedar-Major Singh, three of the game’s characters / victims / accomplices / suspects.

They wanted to create a tool that prioritized words rather than structure. “Most branching story editors are presented as flowcharts,” says Ingold. “But the truth about flowcharts is that they make things seem more complicated than they actually are; they’re spread out all over the page.”

Ink, by contrast, scrolls like a traditional document. “When you’re writing a scene with choices, you have a beginning, middle, and maybe multiple ends. But they’re all going in one direction,” says Ingold. As a lightweight markup language, Ink uses symbols to indicate elements: an asterisk is a choice, a → shifts to another part of the story. “You can essentially write a linear script, then go back through and say, ‘OK, I’m gonna pull this out,’ or ‘I’m gonna branch this bit,’ or ‘I’m gonna make this a long sidetrack that eventually joins back up.’” Bonus: Changing the script is a matter of copy-and-pasting, not rejiggering an entire flowchart. If this sounds interesting, you can check it out yourself: Ink has been open-sourced for the past five years, where Humfrey notes that “hundreds” of games have put it to good use.

(Ink is) like Markdown for interactive fiction.

Joe Humfrey, Inkle co-founder

With Ink, Ingold could focus on the 75,000-word script and its pacing. “Good interactive scenes aren’t good because they have a funky structure. They’re good because they’re well-written,” he says. “The most important thing is allowing the human at the keyboard to get on with [the game].”

Veronica threatens the good commander — at least in this version of the script.

In just about three weeks, Ingold had knocked out a “minimum viable story” on Ink before a single line of Overboard! code was written. “I basically scribbled the opening scene out as is — Ink works really well as a notepad,” he says. “But that scene ends when the steward knocks on the door, and you have to ask yourself: Are you going to lie? It’s such a great first decision, and it leads to, OK, if you lie, what’s the consequence of that?” He smiles at the memory. “Naturally, that makes you want to write the next scene.”

‘As little development as possible’

With the game-jam timeline marching on — “so fast that we barely had time to think about whether this was a good or bad idea,” laughs Humfrey — the other members of the Overboard! team began to think about populating their boat.

By late January, the team had a rough prototype ready to go. “It was very unpolished,” says Humfrey. “It wasn’t even a minimum viable product. But you could play it through, and because the core concept was so simple, we could spend loads of time polishing it.”

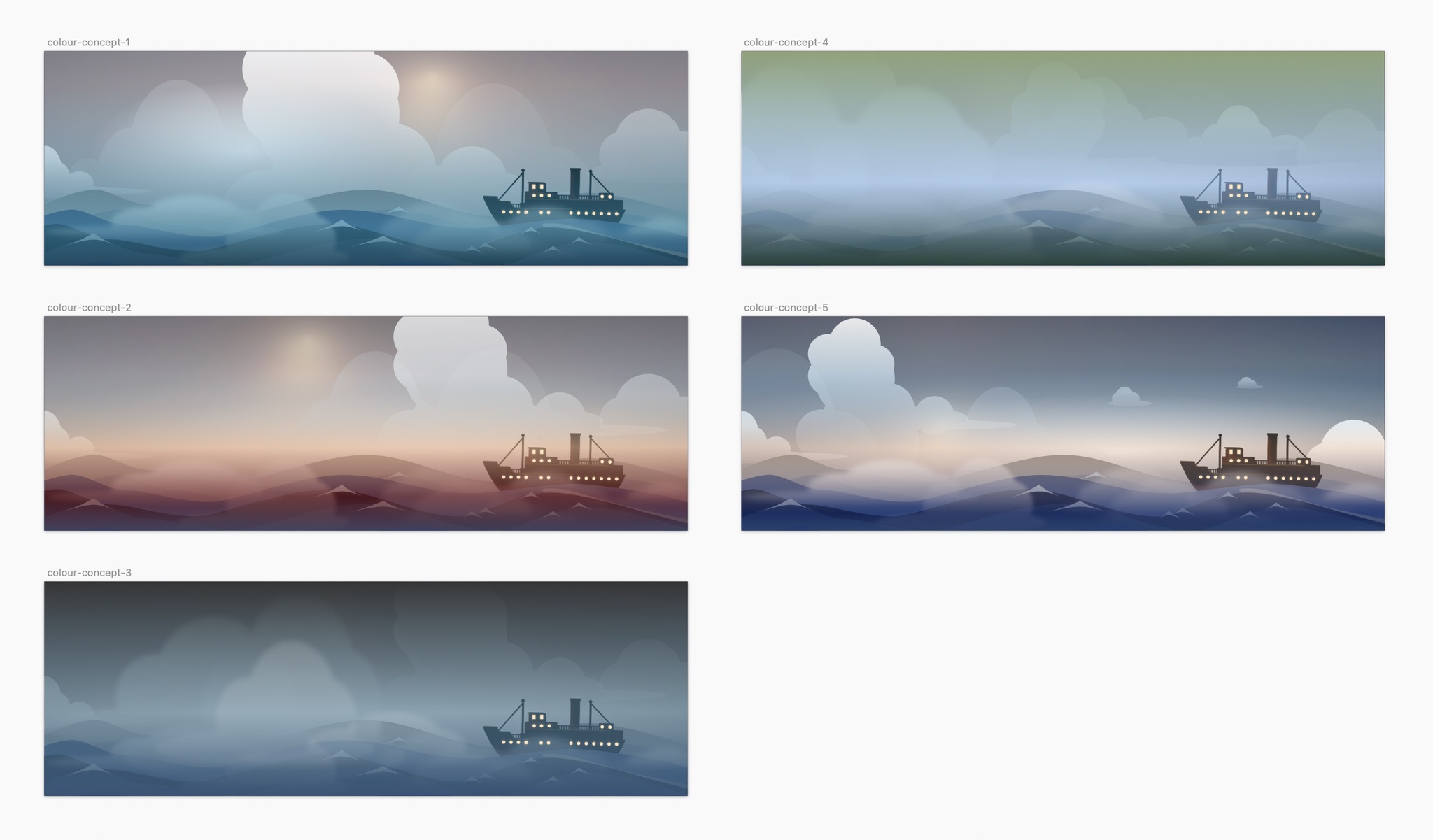

Wyatt and the Overboard! team tried a number of color combinations to set the appropriately sinister mood, eventually settling on the last.

While historically a jack-of-all-trades for Inkle games, Humfrey served strictly as art director for Overboard!, while Tom Kail handled the UI and artist Anastasia Wyatt drew up the cast of shady shipmates. To kick off art direction, Humfrey went back to Inkle’s rich catalog. “The aim was to build it like a sequel to 80 Days,” says Humfrey. “Of course, it diverged and had its own unique UI requirements. But the technology we’d developed internally was already set up for a project like this,” he says.

In addition to the 80 Days skeleton, the team was able to repurpose existing Inkle systems for testing, gathering feedback, and creating animations; Ink even plugs right into Unity. “That’s one of the reasons we could do this in 100 days,” says Humfrey.

People would say, ‘I wonder what happens if I take this object and show it to that person?’ and I’d be like, ‘Yeah! Good question!’

Jon Ingold, Inkle co-founder and Overboard! writer

Once the game was technically operational, playtesting started remarkably early, when the script was only about 30% finalized. “It was like pouring water into a bucket to find the cracks,” Ingold says. “Everything has to make sense. People would say, ‘I wonder what happens if I take this object and show it to that person?’ and I’d be like, ‘Yeah! Good question!’”

Can characters who drink martinis this dramatically be trusted?

Even Ink did its part to help test and polish gameplay. Ingold added a feature that automatically speed-ran the game in Ink to explore the varying branches, so plot holes could be plugged before they even made it into the Unity build. In the final version, the software even keeps track of not only what you know (for instance, that you tossed a diamond earring out of a porthole), but what the other characters know too (for instance, that you’re acting real squirrelly about when you were up on the deck). It’ll also show you the choices you made before, in case you maybe wanna steal those sleeping pills this time around.

“The replayablity mechanic is one of the features we’re most proud of,” says Humfrey. “It’s so easy for a narrative game to feel repetitive, like you’re seeing the same thing multiple times.” To get around it, he looked to films like Groundhog Day, the 1993 comedy about a guy doomed to relive the same day over and over. “That movie cut things down really tightly, so every time they did a time loop you saw just enough context to understand where you were in the loop. I think we managed to make that work quite well.”

As the guilty Veronica, you'll have to plead your case to more than just a few shipmates.

The speedy timeline meant the script didn’t require much editing, since anything extraneous never made it there in the first place. Instead, revisions involved adding dialogue, sprinkling in a few zingers, or testing the boundaries of the game’s tone. (A slapsticky scene in which Veronica finds out a higher power is disappointed with her life choices stayed in; a scene where she attacks someone with a cross did not.)

But sometimes, Ingold just wanted to fit in a scene he liked. “And that’s just sheer joy, because all you’re doing is saying, ‘I wish there was a scene where I could break into the old lady’s room, so I’ll slot that in here.” The characters also lent themselves to wild interactions. “Everybody clashes on the boat,” Ingold says. “Veronica wants everyone to be in awe of her, but the old lady isn’t bothered by her at all. It’s essentially a comedy.”

Humfrey puts it another way. “The thing that Jon’s managed to crack is that Overboard! doesn’t take itself too seriously,” he says.

‘That’s the sort of person she is’

The job of bringing those clashing characters to screen fell to artist and designer Anastasia Wyatt, who, from her home office in Manchester, raced to bring the Overboard! cast to life; in fact, what you’re playing on your device is probably pretty close to what she initially dreamed up. “In a lot of cases, I went with the first design that came into my head,” says Wyatt.

For those designs, Wyatt trawled into the rich potential of the game’s vintage setting, pulling designs from 1930s fashion, magazines, and even sewing pattern books to outfit background players like the irritatingly effective detective Subedar-Major Singh, the curiously sad Clarissa Turpentine, and Veronica (who required extra care since she essentially never leaves the screen). “I saw a picture of this particular hat and the way it sat on a woman’s head,” Wyatt says, “and I could visualize the whole character from that one piece of clothing.”

Wyatt’s early takes on Veronica Villensey were all about hats and hairstyles.

For the backgrounds, Wyatt found herself drawn to the art deco style of vintage British railway posters, all promising exotic globe-trotting adventure. “They were all advertising — ‘Visit Aberystwyth!’ — but they had this great palette of bright, hyper-cheery colors,” says Wyatt.

Wyatt and the design team took pains to make it an inspiration, rather than full recreation; Humfrey also brought in a bit of the comic book pop-art style from the ‘50s (all bold colors and slant-edged panels) to add a bit of playfulness to the dark surroundings. “We tried to push the boundaries, but not so much that it don’t look like the ‘30s anymore,” she says. “You have to find that balance between cartoonifying people and keeping them recognizable in real life.”

Early versions of the caustic but stylish Lady H, complete with outlandish furs.

Wyatt also worked in a few Easter eggs — like Veronica’s stylish hat, which casts an exaggerated shadow. “It’s definitely what you’d see in a character you can’t trust,” says Wyatt (even if, as the game goes on, you learn more about the character’s backstory). Wyatt also draped Lady Honoria Armstrong’s shoulders in an enormous fox fur, a grotesque touch of overamplified high society that’s intentionally out of place. “Obviously you wouldn’t wear a big fur coat with a whole dead fox around your neck in the summer,” Wyatt laughs, “but that’s the sort of person she is.”

‘You should always trade up’

Overboard! is designed for maximum replayability; even if you get away with murder the first time, there’s plenty of story left to unpack. “With any of our games, you might only see 20% of the material on the first playthrough,” says Humfrey. You can replay to score insurance money, check off a list of in-game objectives, or discover hidden storylines. According to the internet, some players have even been known to play through to try and eradicate everyone on the ship.

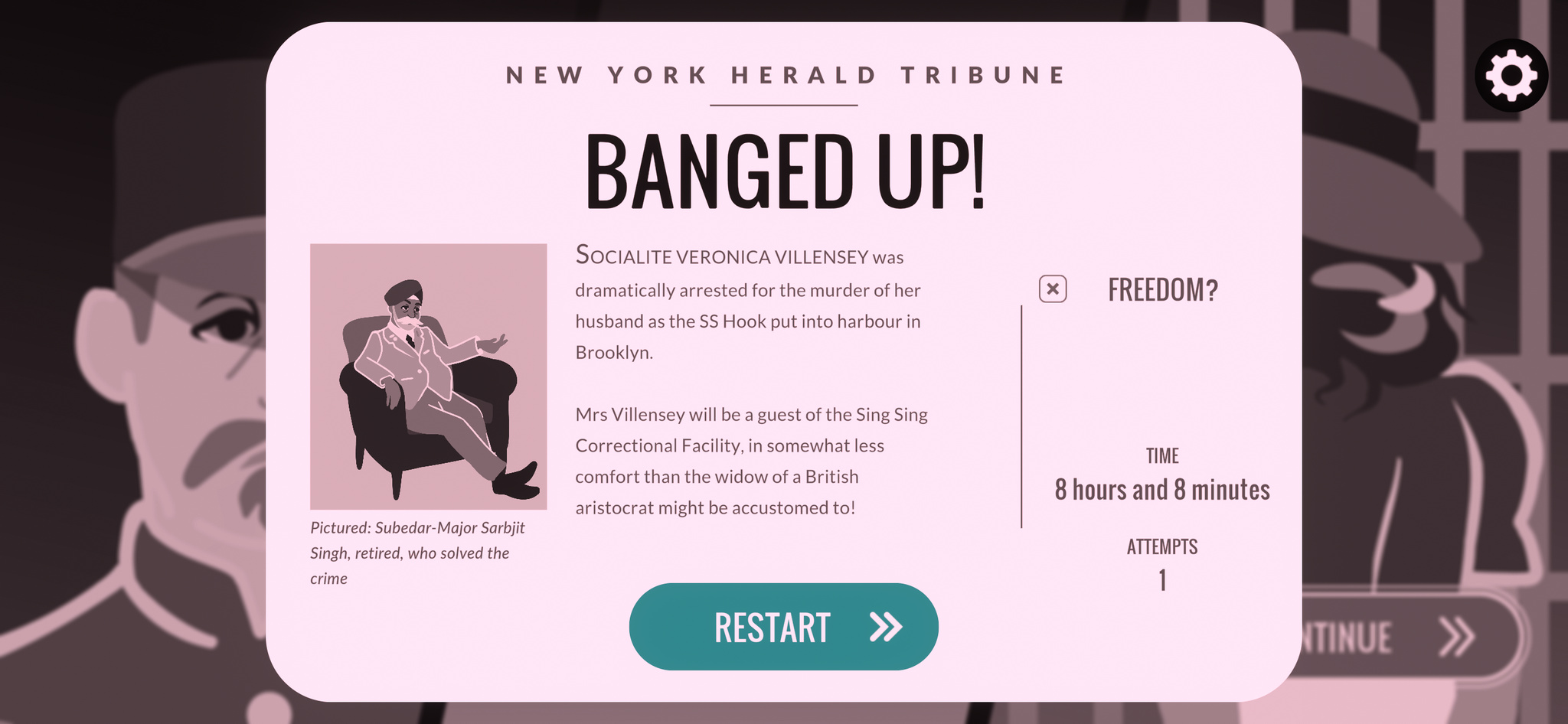

Justice is served — in this ending, anyway.

All of that replayability, the sense that the mystery is yours to do with as you please, is the best possible outcome for such a mystery, says Ingold. Overboard! is done; no updates or additional content are planned, though Humfrey admits to thinking about a sequel. If it happens, Ingold is on board. “As a writer, you should always trade up,” he says. “Is Overboard! what I started off with? No, it’s a version that’s been traded up and up and up.”

Download Overboard! from the App Store

Behind the Design is a weekly series that explores design practices and philosophies from each of the 12 winners of the 2022 Apple Design Awards. In each story, we go behind the screens with the developers and designers of these award-winning apps and games to discover how they brought their remarkable creations to life.