-

System Extensions and DriverKit

One of the next steps in modernizing and improving the security and reliability of macOS is to provide a better architecture for kernel extensions and drivers. Learn how to make this transition with System Extensions and DriverKit.

Resources

Related Videos

WWDC22

WWDC21

WWDC20

WWDC19

-

Search this video…

My name is Joe. And later, I'll be joined by my colleagues Simon and Scott. We're from the Core OS Group and we'd like to tell you about some new developments with Kernel Extensions in macOS 10.15 Catalina.

Kernel Extensions or Kexts, are a technology that's been part of macOS from the very beginning.

Using Kexts, you can build powerful and innovative apps that extend the built-in functionality of the operating system. This power to extend the system is an important part of what makes the Mac the Mac. But there are some problems with Kernel Extensions.

They can be difficult to develop and to debug, they can be a risk to security and privacy on the machine, and they can be a risk to the reliability of the system. It's time for an upgrade.

MacOS Catalina introduces two new technologies called System Extensions and DriverKit.

Using them, your apps can extend the operating system in ways that are more reliable, more secure, and easier to develop than ever before. Here's what we'll talk about today. First, I'll introduce these new technologies and show you how they avoid the problems of Kernel Extensions.

Then, Simon will come up and show us how to build Driver Extensions using DriverKit.

Scott will show us how to write and debug a simple USB driver.

And then, I'll tell you how to include System Extensions in your apps. Let's get started. System Extensions are our first new technology in macOS Catalina. A System Extension is part of your app that extends the functionality of the operating system in ways similar to a Kernel Extension but running in user space outside the kernel.

There are three kinds of System Extensions that you can build in Catalina. They are Network Extensions, Driver Extensions, and Endpoint Security Extensions.

Network Extensions are a replacement for Network Kernel Extensions.

They can filter and reroute network traffic or connect to a VPN.

For more information on Network Extensions, there's a session dedicated to them on Friday morning.

Endpoint Security Extensions are a replacement for Kexts that intercept and monitor security-related events with the KAUTH interfaces. Some of the apps you can build this way are Endpoint Detection and Response and Data Loss Prevention apps. If you're interested in Endpoint Security Extensions, please, come to the Security Labs. There's one happening right now and continuing after this talk and one on Thursday afternoon. The third type of extension is Driver Extensions which are a replacement for Device Driver Kexts using IOKit. In Catalina, you can control USB, Serial, Network Interface, and Human Interface devices.

Driver Extensions are built with DriverKit which is our second new technology in Catalina.

DriverKit is a new SDK with all new frameworks based on IOKit but updated and modernized, designed for building Driver Extensions in user space outside the kernel. Now, that we've met these new technologies let's see how they avoid the problems of Kernel Extensions.

There's a phrase I used in both of those definitions; in user space, outside the kernel. Why does this matter? The kernel is a very unforgiving and difficult environment to program within. The kernel is the conductor of everything that happens on the machine, so it must never stop running, must never wait for anything to happen, and must never crash.

Code in the kernel has to be fast, has to be predictable, has to be frugal with its use of resources like memory, and has to be essentially bug-free.

It's very difficult to write code that meets all of these restrictions.

System Extensions run in user space outside the kernel which means they run in a comfortable modern programming environment.

This makes them easier to develop than Kexts where kernel code has restrictions on when and how it can allocate memory or synchronize between threads.

This means it cannot use most system frameworks such as Foundation since they are not designed to run in this environment.

The only supported language for Kext development is C and C++.

System Extensions, on the other hand, have no such restrictions which means they can be built using any framework in the macOS SDK and can be written in any language including Swift.

There is one exception to this. Driver Extensions, because of their close relationship with hardware, still have some restrictions.

They must use the DriverKit frameworks and run in a tailored runtime which isolates them from the rest of the system. Driver Extensions must be written in C or C++. However, the default is C++17. System Extensions are also easier to debug than Kernel Extensions. Attaching a debugger to the kernel halts the kernel and the entire machine including the debugger. This means you usually need a second machine to debug and you may need special cables or network configuration to connect the machines. The cycle of building, testing, and debugging a Kext can be slow because any crash in the Kext means the whole system has to restart. And the kernel debugger has limited support. It cannot do things like evaluate expressions or print the value of objects. System Extensions, on the other hand, can be debugged and the kernel keeps running.

There's no need to restart if an extension crashes.

You can build, test, and debug all on one machine with full debugger support. But the biggest improvements of System Extensions over Kernel Extensions are in the areas of security, privacy, and reliability. The kernel has many jobs, but one of the most important is to define and enforce the rules of the system's Security Policy. The kernel separates apps from each other and from direct access to hardware. Then, it allows them to share data and system services following the rules of the Security Policy. When a Kernel Extension loads, it becomes part of the kernel.

It has access to everything on the machine. This is where a Kext's power comes from. But it can also be a danger. Because the Kernel Extension is part of the kernel which makes the security rules, it is above the rules. If a Kext has a bug that allows it to be compromised, it can take over the entire machine doing things its developers never intended and its users don't want. There are no security rules that can restrain it.

This means that any bug in a Kext can be a critical security problem. Any bug in a Kext can also be a, can also be a, what's happening? Where are my slides? Any bug in a Kext can also be a critical reliability problem. Because the kernel does not just crash, it panics, and the entire machine has to restart. If you're a Kext developer, you've surely seen this dialog a lot. And unfortunately, so have too many of our users. Let's see how the picture changes with System Extensions.

A System Extension runs in userspace. Like other apps, it has to follow the rules of the System Security Policy. Unlike other apps, System Extensions are granted special privileges to do special jobs. For example, they may have direct access to their associated hardware devices or use special APIs to communicate directly with kernel systems.

If a System Extension crashes, the rest of the system and apps are unaffected and keep running. For all these reasons, we think that System Extensions are a big step forward for the Mac platform. In fact, we think they're such an improvement that we recommend you adopt them immediately. As Sebastian said in the State of the Union yesterday, "We are beginning the process of deprecating Kernel Extensions. MacOS 10.15 Catalina will be the last release to fully support Kernel Extensions without compromises." Specifically, for the capabilities supported by System Extensions and the device families supported by DriverKit, using a Kernel Extension to do that same job is now deprecated and a future release of macOS will not load Kernel Extensions of these kinds. In future releases, we will add more kinds of System Extensions and more device families to DriverKit.

In turn, Kernel Extensions of those kinds will also be deprecated.

So, that's a brief introduction to System Extensions.

They avoid the difficulties of kernel programming by running in user space which lets your apps extend the system in ways that are easier to develop and debug, that protect the security and reliability of our users' data. And now, I'd like to turn it over to Simon, who will show you how to build Driver Extensions using the new DriverKit Runtime. Well, thanks, Joe. As Joe just said, a Driver Extension is a new type of System Extension that controls the hardware device and makes its services available across the whole OS.

We call these new Driver Extensions a Dext.

And our goal is to make the transition from our Kernel Extension to a Driver Extension as easy as possible.

To show you how Driver Extensions work and how you can build your own or transition from a Kext, we're going to talk about four things.

We're going to talk about their lifecycle and how they match and start.

And how they compete with Kexts, and we're going to talk about how to build them with the new DriverKit SDK. And we're going to go over some security features such as entitlements. And finally, we'll talk about some compatibility questions about how you can deploy an app to macOS Catalina and Mojave.

So, let's talk about the lifecycle of a Kext.

Let's look at the process that happens when a device appears that has a Driver Extension. We start with IOKit Matching creating a kernel service to represent your service. This is written by Apple. We then start a process hosting your driver with your DriverKit class instantiated. And the process also as proxy objects for any services it uses such as its provider.

This device is using a USB device or device. This, this device is using a USB device so it has a proxy object to call that represents the kernel device. This means that DriverKit drivers appears to Kernel Extensions and can compete in matching with kernel drivers. You can see them in the registry with tools like IOReg and you can use the IOKit Framework APIs with them. Since DriverKit drivers are separated from the kernel and from each other, another device will have its own process and another instance of the driver. In macOS Catalina, Apple has started to move several of its own drivers to Driver Extensions.

Here, you can see a process that is hosting a USB networking device which is visible in the registry as a normal ethernet device to the rest of the OS. And you can also see some other processes in the registry hosting several HID and serial drivers. So, now we're going to talk about building your Driver Extension with the DriverKit SDK.

We wanted to make building Driver Extensions an easy transition for those of you who currently build Kexts so we started with the IOKit C++ APIs that you are familiar with.

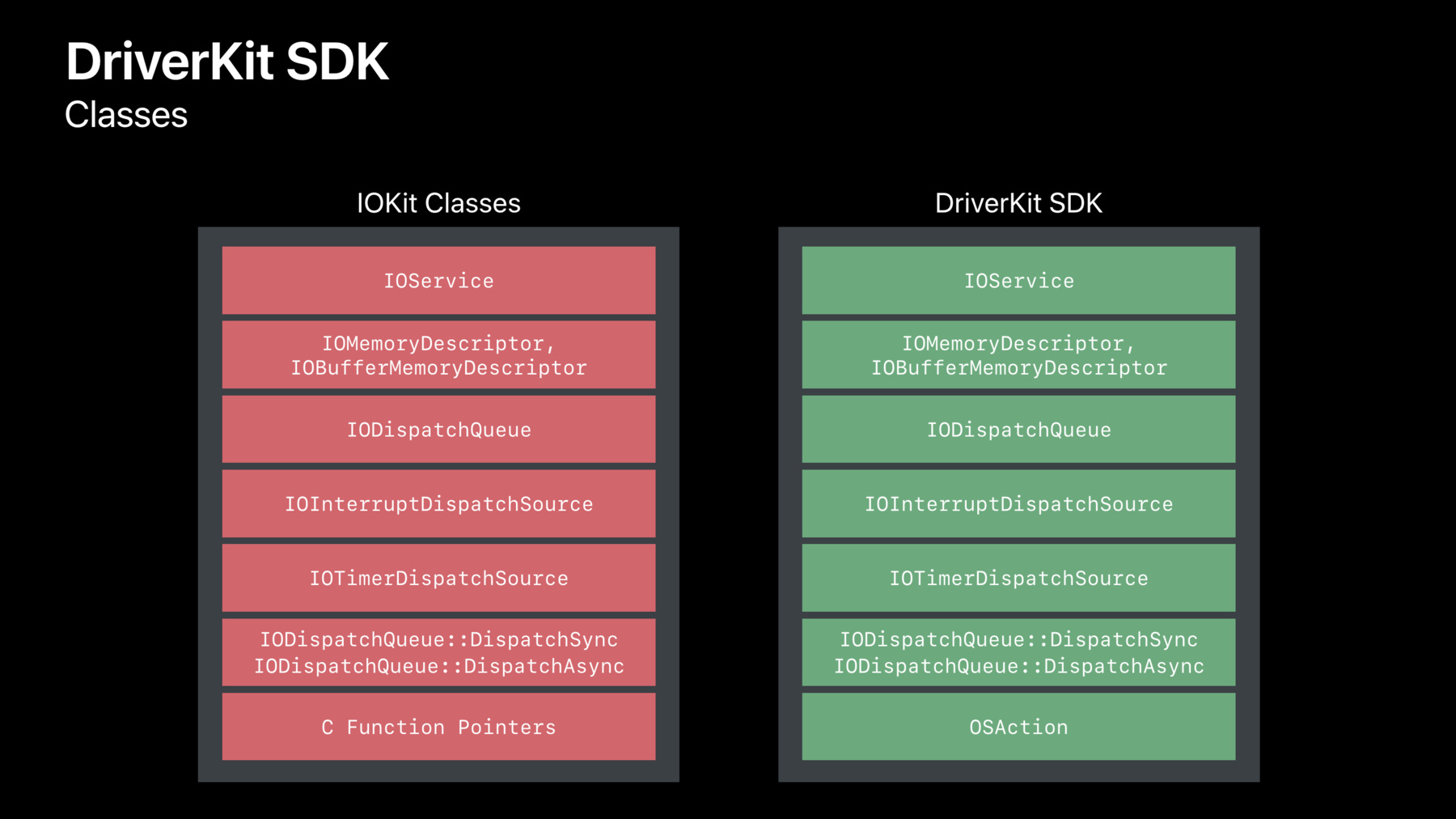

The DriverKit APIs are an extension of the IOKit APIs to userspace. And we have collected them into a new DriverKit SDK that is separate to the macOS SDK. This SDK has a limited API surface for reliability and security and there is no direct access to the file system, networking, or mock messaging. This allows Apple to tailor the userspace process to running drivers and can give it elevated priority and increased capabilities. So, let's talk about some of the classes in the DriverKit SDK. First, the IOService class exists in DriverKit and is very similar to the IOKit class. There also IOMemoryDescriptor and IOBufferMemoryDescriptor classes available that are, again, very similar to IOKit. We also have replacements for the IOWorkLoop and EventSource classes in IOKit. And finally, there's a new class called OSAction that is required to represent a C Function Pointer.

So, let's take a look, closer look at some of these classes. The IOService class has the lifecycle APIs from IOKit like Start, Stop, and Terminate.

For synchronization, every IOService has a default DispatchQueue and all methods are invoked on a queue including interrupts, timers, and completions.

IODispatchQueue is built on the pre-run Grand Central Dispatch code and is a special version optimized for running in the restricted DriverKit environment.

Drivers do have control over their queues and which methods are invoked on which queues for advanced use. The event APIs are similar to the IOWorkLoop model in IOKit but are now based on the Grand Central Dispatch APIs with queues and dispatch sources for interrupts and timers.

The block API is replaced by a command gate and GCD provides synchronization parameters that are easy to use and very likely familiar to you.

There is also an IOSharedDataQueueDispatchSource class that provides a shared memory ring buffer for fast, for low overhead message passing. The last class we'll talk about is OSAction which encapsulates what would be a callback in the IOKit APIs. They are always asynchronous and they hold the callback client's state privately. And they allow the callback to be defined with arbitrary arguments and with type checking in compile and runtime. So, there were some of the classes in DriverKit. Let's look at how we define these classes which is a little different from IOKit.

DriverKit interfaces are described with a new file type with the .iig extension and they are processed by a tool also called IIG.

The IIG file is a class definition that is compiled by Clang and can import C and C++ headers for common types and structures. But it does have some extra attributes to its class and method definitions that allow it to be used, to be used for calling from separate address spaces. Here, you can see a basic class definition that looks mostly normal but it has some extra attributes such as kernel on the class, which means the class is defined in the kernel.

And local on some method declarations which means the method is implemented in a user driver. Some of the families that are available in the macOS Catalina developer preview today are NetworkingDriverKit for creating network interfaces.

HIDDriverKit for creating HID devices, USBSerialDriverKit to make a USB serial device available to the OS, and USB DriverKit to make use of USB device providers in your drivers.

Shortly, Scott will be demonstrating what a USB device support looks like with USBDriverKit. So, now we're going to talk about some security aspects of developing Driver Extensions. There are a few types of driver, of, of entitlement that your Driver Extension will need to obtain.

There's one for all Driver Extensions and there's one to take control of, of a device called the transport entitlement which is specific to the kind of device. And there is also a family entitlement that is required to make available a service into the OS. And Joe will talk later in this session about code signing and the approval process for obtaining these entitlements. Now, we'll have a quick word on shipping products that work on all versions of macOS.

Shipping a product for both macOS Catalina and earlier releases will require you to install a Kernel Extension for older releases but use the System Extensions Framework and provide a Driver Extension on macOS Catalina. So, now Scott will be demonstrating how to make use of the new USBDriverKit Framework. Thanks, Scott. Thanks, Simon. So, today I'm going to show you how to build a simple USB driver that reads data from an interrupt endpoint using the new USBDriverKit Framework. We'll briefly go over how to create a new project in Xcode using the DriverKit Template. After that, we'll take a look at a kernel class versus a DriverKit class. Then, next, I'll go into the details of the implementation in DriverKit. And finally, I'll give a short demonstration of the driver in action and how you can debug your Dext live with LLDB. Creating a new DriverKit project with Xcode is as simple as selecting the proper template during Xcode's new Project Workflow. Once completed, Xcode will have autogenerated a few files to help you begin. The generated project includes the standard files needed to successfully build. As with the Kernel Extension, the project includes the C++ implementation, entitlements, and an info.pist.

In addition to those, Xcode has also generated the IIG file that Simon mentioned earlier. This file contains the class definition for your driver.

So, let's take a look at the class definition for MyUserUSBInterfaceDriver. You can see how this looks very similar to a kernel driver. For example, the same public IOKit Lifecycle method, start and stop existing DriverKit would have been capitalized.

That said, there are a few small but important differences.

First, the DriverKit class requires a different callback with an additional attribute. This attribute indicates that this method conforms to the callback type defined by the IOUSBHostPipe object and enforces compile-time type checking. And second, there are no instance variables declared in a DriverKit class. This is because all instance variables must be allocated by the driver during initialization. So, let's take a look at how that's done for MyUserUSBInterfaceDriver.

First, you need to declare a structure to hold all of your instance variables. All instance variables that would have previously been part of your kernel class should be part of this structure. For this class, we have pointers to the same USB kernel types that a Kext would. Such as an IOUSBHostInterface provider and IOUSBHostPipe object for performing IO. And there's also an OSAction object that will be used to encapsulate the callback for asynchronous IO. Then, you simply need to allocate the structure during your INIT routine. And here's the INIT routine for MyUserUSBInterfaceDriver. It calls INIT on the superclass in the same way a Kext would. And then, it allocates the IVAR structure.

It should be noted that the superclass defines an IVAR's member that must be used to assign the result of the allocation. So, next, we'll take a look at the implementation of Start. This portion of Start is responsible for calling into the superclass and validating the provider.

Here, things are slightly different than the kernel implementation.

You can see the definition is wrapped in a macro IMPL. And this macro is required to support the IPC communication between the user process and the kernel proxy object.

And you can also see that calling super start takes a different form. Next, using the USB DriverKit APIs, you open your IOUSB host interface provider and you allocate your Pipe object.

And then, allocate a memory descriptor to be used for IO.

This should be a fairly familiar paradigm and is basically identical to what's done in a Kext.

In this case, we're performing asynchronous IO, so we need to allocate an OS attribute object to encapsulate the callback.

And then, finally, all that remains is to enqueue the IO.

At this point, assuming the setup was successful, there's an asynchronous read which we'll call ReadComplete when finished. And the ReadComplete method for this driver just prints the number of bytes transferred and the status. If successful, it re-enqueues the IO. So, next, let's take a look at the driver in action. So, in this demo, you'll see some logging I've added to MyUserUSBInterfaceDriver that will print some of the lifecycle methods.

I've also added an infinite loop which we'll debug using LDB. And then, I've also introduced a crash which we can see how is recoverable now using the new DriverKit Framework. So, if I plug in the device you can see INIT and start run just like they would in a Kext. And ReadComplete is being called as data is being transferred to and from the device. Using PS, we can see that our driver is running. And now, we've hit my infinite loop that I added and we can take a look with LDB at what's happening in the driver.

So, from earlier, we can see our PID is 2572, so we need to attach to that process.

We need to find the thread running the ReadComplete method.

You can see, that's thread two.

And here, we've definitely got an infinite loop. And because we're running in userspace, we can modify our loop variable.

And before I continue, if you look closely, you can see there's definitely a null pointer D reference, which will crash the driver. And you can see it's crashed.

But then, immediately restarted without affecting the rest of the system. And then, on unplug you can see your stop and free methods would run as normal.

And so, that's-- -- that's how easy it is to build and debug a new driver with the new DriverKit Framework. Now, I'll hand it back to Joe to talk about how to deliver System Extensions in your apps.

Thank you, Scott.

Now, that we've seen how to build a Driver Extension, I'd like to tell you how to ship a driver or other type of System Extension in your app.

We'll talk about how your extension relates to your app, how to build and package the extension bundle. We'll talk about code signing and entitlements and how to install, update, and uninstall your System Extension. A System Extension is always part of an app. This is a basic principle of the design. There's no such thing as a standalone System Extension.

This is because users think in terms of apps. They purchase apps, install apps, and run apps. Your System Extension should be an implementation detail of your app.

The app is how the user interacts with and controls your extension. Once you've packaged your System Extension into an app, you can distribute that app directly to your users using Developer ID or through the Mac App Store, which has never been possible with Kernel Extensions.

Because of the close relationship between your app and its extensions, your System Extension should be identifiable by the user as related to your app. You should use the CFBundleDisplayName key in the extension's info.plist to give it a good localized name and give it a custom icon that relates to your app's main icon. This way, if the extension is ever shown in the user interface, a user will recognize it as part of an app that they use.

You should also include a usage description string in your extension's info.pList that explains simply what the extension is and does and why a user would run it. Think of this as similar to the usage stings required for calendar or camera access.

For Driver Extensions, use the key OSBundleUsageDescription. And for other types of System Extensions, use the key NSSystemExtensionUsage Description.

Remember to localize these and all other strings for all the languages your app supports. The System Extension itself is a separate sub-bundle of your app with its own executable and info.plist embedded within your application. Here's a peek inside a sample application showing a System Extension in its Contents Library System Extension's folder.

Driver Extension bundles use the .dext filename suffix and the package type DEXT. They use OSBundle keys in their info.plist similarly to Kernel Extension bundles.

Driver Extension bundles should be flat bundles with no contents folder, similar to iOS apps.

System Extension bundles of other types use the .system extension filename suffix and the CFBundlePackageType SYSX, System X tension. In Xcode, your System Extension is a separate target. Xcode has templates for Network Extensions and DriverKit drivers built in.

When you create such a target, Xcode will ask if you want to embed it in an application that's already part of your project. If you do, it will create a Copy Files phase that copies the extension build product into your application. Once you've built your System Extension, you sign it with the same certificate that you sign your app. There is no need for a special Kext certificate, Kext specific signing certificate, anymore.

Normally, the Team ID used to sign your System Extension and your main app must match. This is a security measure. However, you may be building an extension that's intended to be packaged in other developers' apps. For example, a Driver Extension for a common type of USB serial interface chip that's included in many products. If so, there is an entitlement you can use on the System Extension to allow it to be packaged in a different developer's app.

If you sign your System Extension with Developer ID, it must be notarized before it will run on a user's system. For more information on notarization, please watch the session from last year or come to the Notarization Lab later this afternoon.

Your System Extension uses entitlements to describe its capabilities to the operating system; what type of extension it is and what it can do. For example, DriverKit Drive-- Extensions use the Transport and Family entitlements that Simon showed.

Your app that contains System Extensions also should use the com-apple-developer-system extension-install entitlement.

For more information on these entitlements and to request the use of them by your development team, visit developer.apple.com /system-extensions. In the Developer Seed of Catalina for local development, you can turn System Integrity Protection off to disable some of the checks for code signing and entitlements while you are testing.

Please, remember to turn System Integrity Protection on again when you're finished testing. Now that you've built your app with the System Extension, how does the extension get installed on a user's system? There's no need for an installer or a package. Your System Extension stays in your app bundle. Your app uses the new System Extensions Framework and creates an activation request to request that the extension be made available for the system to use. A system administrator will approve this request. Most apps should probably create an activation request during app launch so the extension is made available right away. If your extension has previously been activated and approved, the activation request will return quickly with success. However, you may wish to activate your System Extensions at different points in your app's lifecycle such as after a user has agreed to a license agreement or made an in-app purchase if that's required for your extension.

Once your extension has been activated, the system will manage its lifecycle starting it automatically when it is needed. For example, a Driver Extension will start when a matching hardware device is connected.

To update your System Extension, update your app bundle. A user may install a new version that they download from your website, your auto-updater may update the app bundle in place, or if you release a new version on the app store it will be updated for the user. The next time your app runs and submits an activation request, the system will notice that the extension's version has changed. It will ask your activation request delegate to compare the version numbers following your own version number rules.

If your delegate determines that this is an upgrade, the system will stop the old version of the System Extension and start the new one. If a user wishes to uninstall your application, when they move it to the Trash, all of its extensions will automatically be deactivated, as well. There is a deactivationRequest API if you wish to use it, but there's no need for a dedicated uninstaller.

So, today we introduced System Extensions, the replacement for Kernel Extensions that lets your apps extend the system in ways that are more reliable, more secure, and easier to develop than ever before.

We saw how to use the DriverKit SDK and frameworks, which are a modernized update of IOKit to build a driver. And we saw how to write and then debug an example USB driver all on one machine.

Finally, we talked about how to include System Extensions in your apps.

If you have any questions, we would love to answer them at the Core OS Labs. There's one later today and one Thursday morning.

You may also wish to visit the Security Lab happening now or on Thursday afternoon or the Networking Lab on Friday morning. Thanks, very much, and enjoy the rest of WWDC. [ Applause ]

-