-

Explore UI animation hitches and the render loop

Explore how you can improve the performance of your app's user interface by identifying scrolling and animation hitches in your app. We'll take you through how hitches happen in the render loop, and explain how to measure hitch time ratio and fix the issues that most impact people using your app.

Resources

Related Videos

WWDC23

WWDC21

Tech Talks

-

Search this video…

Hi, I'm Patrick, and I work on a performance team at Apple. Today we'll be discussing scrolling and animation hitches in your apps and look at the Render Loop in detail.

First, we'll get a general sense of what is a hitch. Then we'll discuss the Render Loop and the different types of hitches that can happen.

Finally, we'll discuss how to measure hitches.

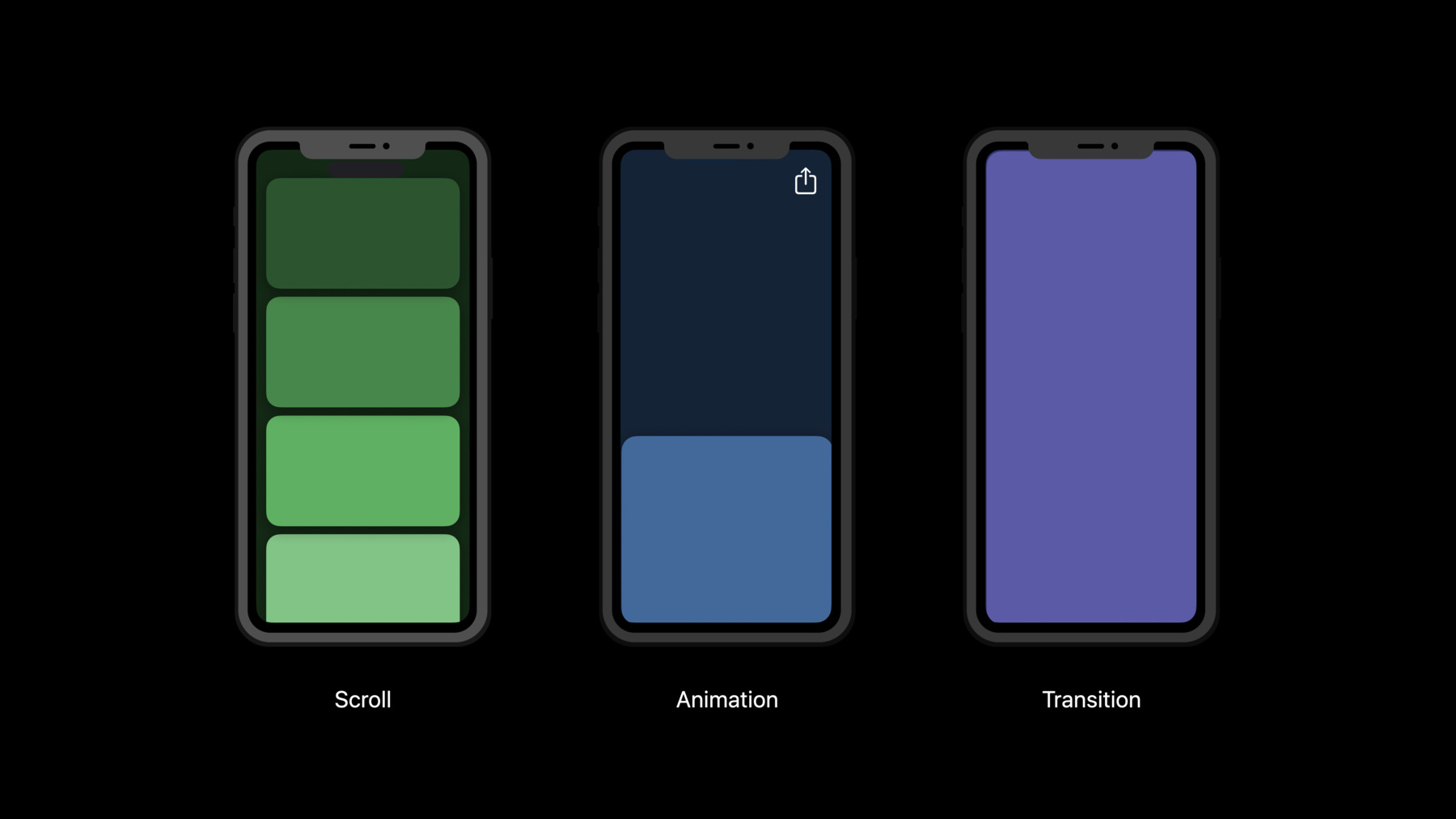

So first, what is a hitch? In your app, a person might drag their finger across the screen to scroll. They might tap a button and expect feedback or transition between views in a hierarchy. These animations build a visual sense of connection between people and content on screen.

Animation hitches can cause jumps in animations and break that connection, causing confusion instead of delight.

A hitch is any time a frame appears on screen later than expected. Let's look at a common example of scrolling a collection view.

Here we have a meal planner app that helps us curate our favorite recipes. As a user drags their finger up the screen, the scroll view responds by moving the content up. But while scrolling, we notice a jump in the content.

If we look at this frame by frame, we can see our finger moving with the content in the first three frames, but in the next frame the content appears to stall. That's because the third frame actually repeated, staying on the display for another frame. Finally comes the fourth frame, and it appears to jump forward to where our finger is.

The third frame repeated because the fourth frame arrived late, and the user saw a hitch.

Hitches are caused when the Render Loop fails to finish a frame on time. So let's look into the Render Loop.

The Render Loop is a continuous process by which touch events are handed to an app, and then changes to the UI are sent to the operating system where the frame is finalized. It's a loop, and it happens at the device's refresh rate.

On iPhone and iPad, this is 60 frames per second, which means a new frame can be displayed every 16.67 milliseconds. On iPad Pro, this is 120 frames per second, which means a new frame can be displayed every 8.33 milliseconds.

At the beginning of a frame, the hardware emits an event called a VSYNC. The VSYNC denotes when a new frame must be ready. We highlight them in the display track, so it's easy to see the deadline. The Render Loop is timed to VSYNCs. It must hit checkpoints along the way in order to have a frame ready.

It's broken up into three stages. The first stage is in your app, where events are handled and changes are made to the UI. That work must complete before the next VSYNC, so the next stage can begin. The next stage happens in a separate process called the render server. This is where your UI is actually rendered. This stage must also complete before the next VSYNC, so that the frame can be displayed, which is the third and final stage.

An important caveat to the three-stage process is that the frame is processed for two frames before display. We call this double buffering, but there is another mode. To avoid hitches, the system may switch to triple buffering, where the render server is given one extra frame duration to complete its work. Since this is a fallback mode, we're gonna focus on double buffering while talking about hitches in the Render Loop.

Overall, the entire Render Loop is made up of five phases. The loop begins with the first phase, the event phase. Here your app handles touch events and decides if a change is needed in the UI. Next is the commit phase. In the commit phase, your app updates its UI and submits that to the render server for rendering. On the next VSYNC, the render server takes that submission, and in the render prepare phase, prepares it for drawing on the GPU. In the render execute phase, the GPU draws your UI into a final image, so on the next VSYNC the frame can be displayed to your user.

Each stage is critical to having a smooth user experience every frame, even the render work. Although it happens in a separate process, it does work on your app's behalf, so it's on you to ensure your layer tree can be processed and drawn in time. To understand this a little further, let's look at an example.

In this example, we're gonna follow this frame through the Render Loop to see each phase along the way. First is the event phase, where the app will receive events. These events are things like touches, networking callbacks, keyboard presses and timers. The app can respond to these events in any way by altering its layer hierarchy. For example, the app can change the background color of a layer, or even change a layer's size and position.

But when the app updates the bounds of a layer, Core Animation also calls setNeedsLayout. This identifies all the layers, which must recalculate their layout in response.

The system will coalesce these "need layout" requests and perform them in order during the commit phase to reduce duplicate work.

If any layout is needed, the commit phase will automatically start once the event phase finishes. First, the system takes all the layers requiring layout and lays them out one at a time, from parent to child.

Layout is a common performance bottleneck, so keep in mind that your app only has a couple of milliseconds to complete this work. Some views also require custom drawing, like labels, image views or just any view overriding drawRect. If these views require a visual update, they must call setNeedsDisplay. Like layout, the system will coalesce these requests to perform them once all layout has completed.

During the drawing process, every custom drawing layer will receive a texture-backed Core Graphics context which they'll draw into.

As far as Core Animation is concerned, these layers are now just images. And now that all layers have laid out and drawn, the entire altered layer tree is collected and sent to the render server for rendering.

Now we are in the render server, which is responsible for turning our layer tree into an actual displayable image. In the prepare phase, the render server iterates through the app's layer tree and prepares a linear pipeline that the GPU can then execute.

Starting from the top layer, it works its way from parent to child and sibling to sibling so that the layers are arranged from back to front.

Next, this linear pipeline is passed through the GPU, where each layer is composited into a final texture. Some layers can take longer to render, and this is another common performance bottleneck we will discuss shortly.

Great. So once the GPU executes and renders the image on the right, it's ready to be displayed on the next VSYNC.

Each phase of the Render Loop is performance-sensitive and has a deadline. The deadline is the next VSYNC. To hit the target frame rate and maintain low input latency, this entire process is actually happening in parallel every frame.

This way, the pipeline becomes concurrent, and our app can prepare a new frame while the system is rendering the previous one. This is why any missed deadlines are so important.

Now that you see how the Render Loop works, let's dive into what types of hitches you might see in your apps.

There are two primary types: commit hitches, which happen within the app's process, and render hitches, which happen in the render server.

A commit hitch is when the app takes too long to process events or commit.

Here, the commit takes too long and misses the deadline, so in the next VSYNC, the render server has nothing to process and now must wait for the next VSYNC to begin rendering. And now we have delayed the frame delivery time by one frame. In milliseconds, that's 16.67 milliseconds on an iPhone or iPad. We call this delay duration "hitch time," and we measure it in milliseconds.

If the commit work took even longer and went past the next VSYNC, then the frame would be late by two frames, or 33.34 milliseconds.

That's 33.34 milliseconds that the user is not seeing a smooth scroll.

To understand more about commit hitches and how you can fix them in your apps, check out "Find and Fix Hitches in the Commit Phase." The second type of hitch is a render hitch. These happen when the render server is unable to prepare or execute our layer tree on time.

Here, the render execute phase takes too long and goes over the VSYNC boundary. The frame was therefore not ready on time, and the green frame was displayed one frame later than expected.

Once again, we have a 16-millisecond hitch time.

To understand more about render hitches and how to optimize your layer tree, check out "Demystify and Eliminate Hitches in the Render Phase." Great. So those are the two main types of hitches. Now let's turn our focus to how we measure and quantify hitches.

We looked at hitch time in the previous slides. It's very useful when talking about a single hitch, but can become intractable when discussing longer-term events like scrolls, animations or transitions.

Firstly, it's difficult to compare unless each scroll or animation takes the exact same amount of time, and therefore the exact same number of frames.

What's worse is that iOS devices do not always update the screen. If there are no commits sent to the render server, no new frame is submitted. That makes it even harder to compare hitch time across tests and devices. So instead, we use a metric called "hitch time ratio." Hitch time ratio is the total hitch time in an interval divided by its duration. Because it's normalized to total time, we can compare it across experiences. It's measured in hitch milliseconds per second, so it represents the amount of milliseconds the device was hitching every second. To learn about how you can use this metric to measure your own app performance, check out "What's New in MetricKit." To see how to track hitch time ratio in your test suite, check out "Eliminate Animation Hitches with XCTest." Finally, let's look at an example where hitch time ratio can be used.

Here we have 30 frames, which on an iPhone is half a second's worth of work. Each frame hits its deadline, and the user sees no hitches. The hitch time is zero, and hitch time ratio is also zero.

But now we see a display track on the bottom with disjoint intervals.

Some frames are on screen longer than others, and some commits and renders are causing hitches. If we add up this hitch time, we get 100.02 milliseconds. Over half a second, we have a hitch time ratio of 200.04 milliseconds per second. This is just an example. In general, these are the target hitch ratios we recommend and use in our tools here at Apple. Although this goal is zero hitch milliseconds per second, anything under five hitch milliseconds per second is considered good and mostly unnoticeable by a user. Between five and ten hitch milliseconds per second, the user is going to notice some interruptions, and these should be investigated. Over ten hitch milliseconds per second, hitches are greatly impacting the user experience, and you should immediately investigate how to optimize your Render Loop.

To recap, today we discussed the Render Loop and how a new frame is displayed to the user. We looked at what a hitch is and the two types, a commit hitch and a render hitch.

Finally, we defined the hitch time ratio to measure the amount of hitching experienced by users within a given duration.

To learn more about the types of hitches and how to catch and fix them in your apps, please check out our two talks on commit hitches and render hitches.

We can't wait to see your buttery smooth apps, and thanks for watching.

-