-

Go small with Embedded Swift

Embedded Swift brings the safety and expressivity of Swift to constrained environments. Explore how Embedded Swift runs on a variety of microcontrollers through a demonstration using an off-the-shelf Matter device. Learn how the Embedded Swift subset packs the benefits of Swift into a tiny footprint with no runtime, and discover plenty of resources to start your own Embedded Swift adventure.

Chapters

- 0:00 - Introduction

- 0:25 - Agenda

- 0:46 - Why Embedded Swift

- 2:30 - Showcase

- 2:47 - The plan

- 3:39 - Getting started

- 6:19 - Using Swift's interoperability to control the LED

- 7:12 - Using an ergonomic LED struct

- 10:07 - Adding the Matter protocol

- 13:43 - Using a Swift enum in the event handler

- 16:52 - Demo summary

- 17:34 - How Embedded Swift differs

- 19:48 - Explore more

- 21:32 - Wrap up

Resources

- Tools used: Neovim

- Swift MMIO

- Swift Forums Embedded Discussion

- Swift Embedded Example Projects

- Embedded Swift User Manual

- A Vision for Embedded Swift

- Swift Matter Examples

- Forum: Programming Languages

Related Videos

WWDC21

-

Search this video…

Hello and welcome. My name is Kuba Mracek, and as you know, Swift is a powerful language that can be used to build applications both for Apple platforms and beyond. Today, we’re going to take it to new and exciting, but smaller, places — embedded devices. I’ll start by introducing Embedded Swift. Then I’m going to show you in a demo how it can be used to build something practical. I’ll go over how Embedded Swift is different from the Swift you use to write desktop and mobile applications, and finally I’ll share resources that you can explore to learn more. Let’s jump in! Today, you can use Swift to build many different types of software: You can target mobile devices, desktop computers, servers.

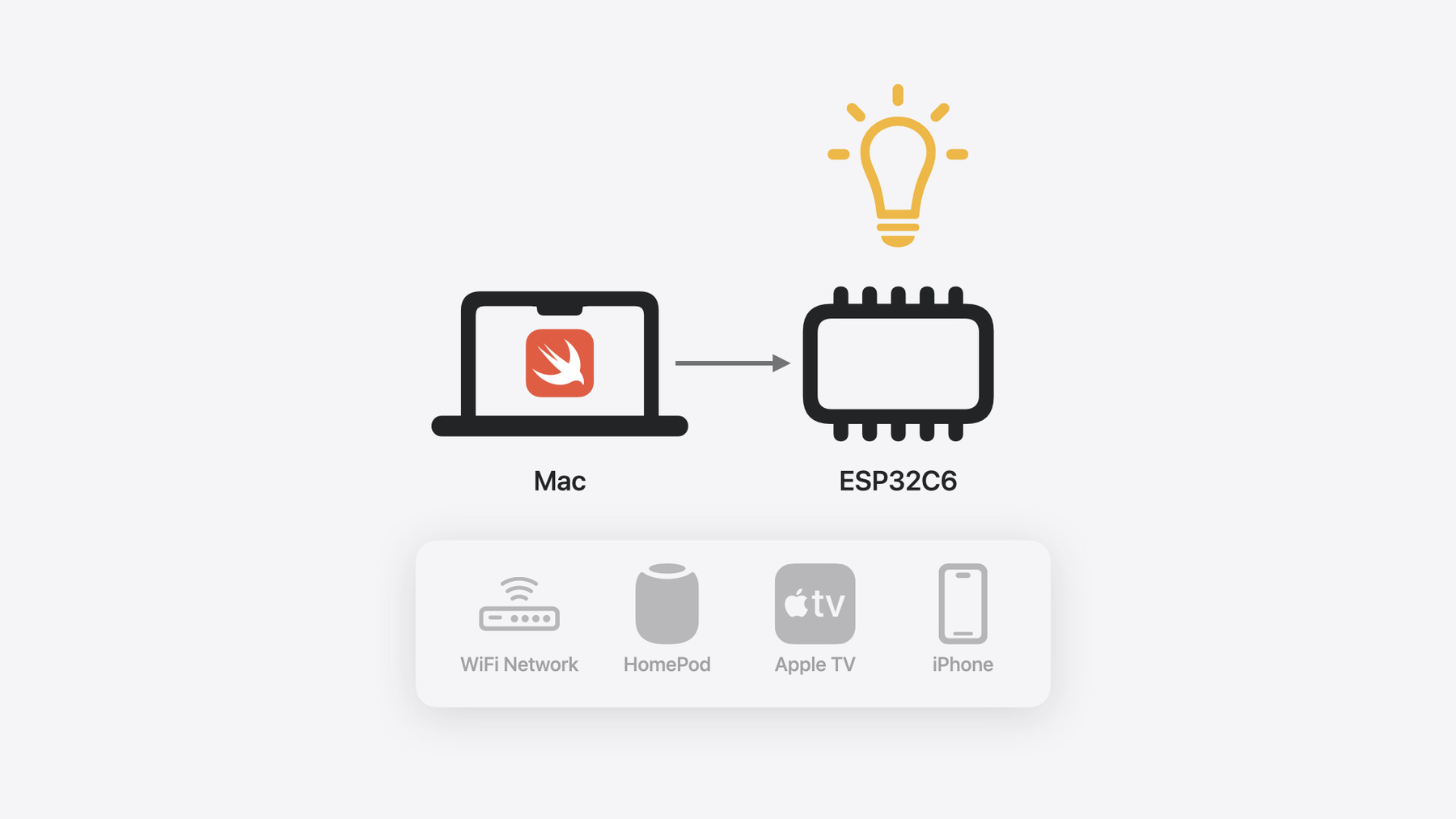

In this session, we’re going to talk about using Swift in a new area: on embedded devices, which we are surrounded by in our daily lives — smart lights, thermostats, alarms, smart fans, music devices, light strips, and many other common gadgets are built using programmable microcontrollers. Today, I would like to show how you — as either a hobbyist or even a more serious developer — can use Swift to program these embedded devices. For that, we’re introducing Embedded Swift — a new compilation mode specifically suited for constrained embedded devices. Historically, C and C++ were the commonly used languages in this area. But now, we’re enabling using Swift in these places, and that brings to embedded developers the benefits of Swift, like its ergonomics, safety features, and ease of use. Embedded Swift is of course suitable to program microcontrollers in embedded devices, but also kernel-level code and other low-level library code that might be, for example, sensitive to not gaining new dependencies. Apple devices use Embedded Swift on the Secure Enclave Processor, and Swift’s memory safety is a huge benefit for the platform. Embedded Swift is a subset of Swift, covering most of the language you know and love — it’s a full-featured subset that includes support for value and reference types, closures, optionals, error handling, generics, and more. Now, let’s take a look at Embedded Swift in a live demo. Before we start: Embedded Swift is currently an experimental feature, it’s not source stable, yet. It’s under active development, and the best way to use it is with a preview toolchain from swift.org. In this demo, I’m going to build a prototype of a very simple HomeKit accessory. A color LED light. I’ll start by having a working HomeKit setup — that means a WiFi network, and some existing Apple devices all connected to it. I’m going to take a programmable embedded device, concretely an ESP32C6 development board, which has a RISC-V microcontroller. And, it’ll have a color LED attached to it. I’ll use a Mac to connect to the device over a USB cable, and I’ll write a program in Embedded Swift that implements a HomeKit accessory, which I will then flash onto the device. The device will then join my WiFi and the HomeKit network, and it can be controlled from the Home app on any of the Apple devices.

Let’s get started. I’m using Neovim and CMake, and right now, this is just a template project to show the very basics and to get our Embedded Swift code up and running. The project is using a 3rd party SDK, which I got from my device vendor it’s an SDK written in C. And because I don’t want to modify that SDK, I can simply use a bridging header, to import all the SDK’s APIs into Swift.

I need some simple CMake logic to be able to build my Swift code on top of the vendor’s SDK and their build system, which also requires a few more boilerplate files: Like the YAML file, the CSV file and the “sdkconfig” file.

These are needed for any project built on top of this SDK, and I have set those up based on existing examples from the vendor, and just added Swift on top of that.

Let’s go back to my Swift source code. My editor has LSP integration, so it show me the definitions and documentation for functions and types I’m using.

It can can give me rich and semantical autocompletion.

And if I write code that doesn’t make sense...

I get immediate errors and warnings telling me what’s wrong. Let me now plug-in the device.

I’m going to be programming this device over USB, but my breadboard also has a separate battery, so once its programmed we will be able to unplug the device and still use it. But first, let’s get the most basic Swift application working and running on the device. The SDK I’m using provides tools for that.

I’m going to run this convenient Python script that the vendor is providing. It allows me to build, flash, and monitor the device, all with a single command.

As I run it, we can observe that the firmware is being built, then uploaded to the device, and then we receive logs back from the device. And with that, we now have signs of life of our first Embedded Swift application running on an embedded device. Now, let’s add code that does something more useful. Swift’s interoperability gives us access to all the APIs in the vendor’s SDK. If I want to control the LED on the device, I can use the existing C APIs in the SDK for that.

Let’s call these APIs with values that mean “blue color”, “100% saturation”, “80%” brightness.

And let’s save and upload this version of our code to the device.

I’ll run the same command as last time.

In a few seconds, once the firmware is uploaded and the device reboots, we can now control the color and brightness of the LED.

Now, using Swift to just call C APIs for everything would defeat the whole purpose. It’s very useful that we can do that, but it’s even better to build some wrappers and abstractions over those, so that we can write our application in clean, intuitive, and ergonomic Swift code. In this version, I have prepared an LED object. Let’s jump to its definition.

This is some helper code I wrote earlier, and it wraps the C APIs into a nice Swift layer. It provides useful properties with some ergonomic types, for example the enabled property is a boolean, the brightness property is an integer. Let’s go back to the file with the main application logic. Using the LED object, we can now write really straightforward and intuitive code.

On start, let’s set the color to red.

And brightness to 80%.

Code like this is extremely readable and clear. Let’s add some more.

In a loop, we’ll wait 1 second, flip the state of the LED. And if we’re turning it on, then we’ll ask for a new color expressed by a hue and a saturation value. The hue will be random, and saturation will be 100%. All of this Embedded Swift code really feels just like writing regular Swift. Most of the language is simply available. I’ll upload the firmware one more time Let’s see if the result works. Once the program boots and runs, our device should be blinking its LED with a randomly changing color.

Great! This is exactly what we wanted. Building the layer for the LED object is what really gives us the power of Swift: High-level APIs that let us write clean, readable code. So far, we’ve seen how Embedded Swift can nicely integrate into your workflows. You can use it with a vendor-provided SDK, and you can get your IDE or text editor to provide full autocompletion, show definitions, and documentation. Using Swift’s interoperability, you can call existing C APIs from the SDK directly in Swift code. But often it’s valuable to wrap C APIs into a layer that provides ergonomic and intuitive APIs for our core application logic.

Now that we have the basics working, let’s continue building an actual HomeKit accessory. For that, we’re going to use “Matter” protocol. Matter is an open standard for building smart home accessories. It’s described in depth in a WWDC session from 2021, I encourage you to watch it if you’d like to know more. In the SDK I’m using, Matter is provided as C++ APIs, and we can use Swift’s interop again to use this functionality that will gives us all the infrastructure pieces, like device discovery and commissioning, for free. And as soon as we have a device that implements the Matter protocol, it will automatically work in HomeKit, because it supports Matter accessories natively. Let’s start again with just an empty application that doesn’t do anything. And to work with Matter, we need to know a little bit about its data model and terminology. This is the rough high-level task list that we’ll have to do, to implement a Matter device. We’ll need to create what’s called a root node, which represents the entire Matter accessory. Then we’ll need an endpoint, in our case that’s going to be the color LED light, and that’s also going to be the object that has a state, for example the color and brightness, and can receive commands, for example to turn the light on or off. Then we’ll connect the endpoint to the node, and the node to an “application” object. I already wrote a simple wrapper layer around the C++ Matter APIs that’s what I have in this “Matter” subdirectory.

It’s exactly the same approach we used to give ourselves nice APIs for working with the LED light. Using that, we can fill in the top-level logic easily.

First we create the root node.

Then we create and configure the endpoint.

This is our color light, and notably it has an eventHandler — a closure that is triggered every time an event from HomeKit is sent to this endpoint. A closure is a very natural mechanism for a callback. We don’t have to deal with unsafe function pointers or untyped context arguments which are a common solution for callbacks in C. Next, let’s register the endpoint. And finally, set up and start a Matter application.

For now, the logic just prints all the events, but we’ve now built a valid Matter application. So let’s flash this application to the device.

It will take a while to start up. Now normally, you would go through a setup process for a new accessory. I have already previously done that, and I have registered this device in my HomeKit network already, so it already knows which WiFi network to join. As soon as it does that, it’ll shows up in the Home app on my Mac, and on my other devices as a “Matter Accessory”. It shows up as a smart light, and I can control it right here from the Home app on my Mac. I can turn the light on and off, and as I do that, we receive events for those commands that show up in our device logs.

So far, we have just been logging the incoming events. Let’s make them really do something! And let’s wire them up to our LED object that we’ve used previously. Inside the event handler, we’ll want to react to different attributes being set. And because the attribute is a Swift enum, we can use a switch statement, and the autocompletion will tell use which cases we have to handle. Let’s fill in the code for the different attributes. Based on which event we receive, we will want to set the enabled property if we need to turn the light on or off. Or we’ll set the brightness property, where we also need to scale the value appropriately. And very similarly, we can handle color changes, setting a new hue, a new saturation, or a new color temperature. This should be all we need. Let’s flash this program to the device and test it out! While the program is starting, I’d like to point out how useful and ergonomic Swift enums are.

In the simplest case, enums just represent one choice out of a set. For example the .onOff case or the .levelControl case of the attribute.

But they can also have associated values. For example the .colorControl case has a payload, and thanks to Swift’s pattern matching, I don’t need a second nested switch statement. I can just match the enum case together with the payload.

I’m also using enums to represent the color property, which can either be hue plus saturation or a temperature.

These cases even have different payload types, the first one has two integers as the payload, and the other one needs just one integer. This altogether makes Swift enums really powerful and expressive, and they allow us to write this simple, concise, readable logic. Now that the device has started, I can unplug the USB cable and use the battery to power it.

And we can control this device wirelessly from the Home app. Let’s turn the light on.

And off. Let’s see if we can change the brightness.

Or choose a different color temperature.

Or perhaps customize the color completely. Let’s try a few different ones.

Awesome, I think our prototype of a smart light works great! We have successfully built a HomeKit-enabled smart light using Embedded Swift. And if you’d like, this demo project, and setup instructions are available on GitHub. We’ve seen how we can get a basic prototype of a HomeKit-enabled device up and running very quickly, by leveraging Swift’s interop capabilities. There is no need to re-implement the entire Matter protocol in Swift. We can just use the existing implementation from Swift. Swift encourages clean and intuitive design and implementation of your code, and it improves readability and safety over C and C++, as we’ve seen, for example, when using closures as an ergonomic solution for callbacks. In the demo, we’ve seen how Embedded Swift feels like regular Swift, and it does indeed include most of Swift’s language features, but there are some differences. Embedded environments are commonly very constrained, and they need small and simple binaries for programs to fit. Memory, storage, and CPU performance are typically very limited. Because of that, Embedded Swift disallows certain features to meet these requirements. As an example, let’s consider how runtime reflection works. To inspect the children of a type, it needs to access the metadata record for the type. This includes the fields’ names, offsets, and types, which in turn reference other metadata records, and so on and so on. These records all add up and can have an unacceptable codesize cost for embedded devices.

To avoid that, runtime reflection using the Mirror APIs is disallowed in Embedded Swift, and it’s only available in full Swift. For the same reason, to avoid needing metadata at runtime, metatypes and “any” types are also disallowed. But don’t be alarmed, the vast majority of the Swift language is available in Embedded Swift. Embedded Swift is strictly a subset compared to full Swift, and not a variant or a dialect. So there won’t be any differences in behavior between Embedded Swift and full Swift. All code that works in Embedded Swift will also work in full Swift.

When you try to use a feature that’s not available in Embedded Swift, the compiler will tell you. In this example, I have tried to use an any type.

To avoid that, I can replace this use of any Countable with generics instead. In this code snippet, it’s as simple as swapping any Countable for some Countable, which turns this function into a generic function. Generics are fully supported in Embedded Swift, as the compiler can specialize generic functions. And the result of that is code that does not need expensive runtime support or type metadata. There’s so much more to explore about Embedded Swift. As part of the Swift Evolution process, a vision document for Embedded Swift has been published and accepted. This document describes the high-level design, requirements, and approach of Embedded Swift, and it’s a great introduction into the compilation mode and the language subset. If you’re trying out Embedded Swift, I recommend reading the “Embedded Swift -- User Manual”. It describes how to get started, what you should and shouldn’t expect, and also some details that you will likely need to know when interacting with your vendor’s SDK and build system, for example, which compiler flags to use and which dependencies you will need to satisfy.

We have published a set of example projects written in Embedded Swift on GitHub, and they cover a range of embedded devices that have ARM or RISC-V microcontrollers. This includes popular embedded development boards, as well as some other devices like the Playdate gaming console. The examples also show how to use various build systems and integration options. They can give you a sense of what all can Embedded Swift do, but also serve as templates for your own ideas. When writing code that runs on an embedded device, you often need to interact with low-level hardware registers. To help you with that, we have published “Swift MMIO”, a library that provides APIs for safe, structured, and ergonomic operations on memory mapped registers. And finally, the Swift forums now have a new “Embedded” subcategory and that’s the right place to take your experiments, questions, and discussions next.

We have seen how to use the new compilation mode — Embedded Swift — to program embedded devices. It’s currently available as a preview, and works best with nightly toolchains from swift.org. Currently, ARM and RISC-V chips of both 32-bit and 64-bit variants are supported, but Embedded Swift is not really hardware specific and it’s quite easy to bring it to new instruction sets. Go try out Embedded Swift, build some cool electronics projects and share your experience and feedback on the Swift forums. Thanks for watching, and have a great WWDC.

-

-

3:50 - Empty Embedded Swift application

@_cdecl("app_main") func app_main() { print("🏎️ Hello, Embedded Swift!") } -

6:48 - Turning on LED to blue color

@_cdecl("app_main") func app_main() { print("🏎️ Hello, Embedded Swift!") var config = led_driver_get_config() let handle = led_driver_init(&config) led_driver_set_hue(handle, 240) // blue led_driver_set_saturation(handle, 100) // 100% led_driver_set_brightness(handle, 80) // 80% led_driver_set_power(handle, true) } -

8:32 - Using an LED object

let led = LED() @_cdecl("app_main") func app_main() { print("🏎️ Hello, Embedded Swift!") led.color = .red led.brightness = 80 while true { sleep(1) led.enabled = !led.enabled if led.enabled { led.color = .hueSaturation(Int.random(in: 0 ..< 360), 100) } } } -

12:44 - Matter application controlling an LED light

let led = LED() @_cdecl("app_main") func app_main() { print("🏎️ Hello, Embedded Swift!") // (1) create a Matter root node let rootNode = Matter.Node() rootNode.identifyHandler = { print("identify") } // (2) create a "light" endpoint, configure it let lightEndpoint = Matter.ExtendedColorLight(node: rootNode) lightEndpoint.configuration = .default lightEndpoint.eventHandler = { event in print("lightEndpoint.eventHandler:") print(event.attribute) print(event.value) switch event.attribute { case .onOff: led.enabled = (event.value == 1) case .levelControl: led.brightness = Int(Float(event.value) / 255.0 * 100.0) case .colorControl(.currentHue): let newHue = Int(Float(event.value) / 255.0 * 360.0) led.color = .hueSaturation(newHue, led.color.saturation) case .colorControl(.currentSaturation): let newSaturation = Int(Float(event.value) / 255.0 * 100.0) led.color = .hueSaturation(led.color.hue, newSaturation) case .colorControl(.colorTemperatureMireds): let kelvins = 1_000_000 / event.value led.color = .temperature(kelvins) default: break } } // (3) add the endpoint to the node rootNode.addEndpoint(lightEndpoint) // (4) provide the node to a Matter application, start the application let app = Matter.Application() app.eventHandler = { event in print(event.type) } app.rootNode = rootNode app.start() } -

18:03 - Reflection example

// Reflection needs metadata records let mirror = Mirror(reflecting: s) mirror.children.forEach { … } struct MyStruct { var count: Int var name: String } -

18:57 - Unavailable features will produce errors

// Unavailable features will produce errors protocol Countable { var count: Int { get } } func count(countable: any Countable) { print(countable.count) } -

19:24 - Prefer generics over “any” types

// Prefer generics over “any” types protocol Countable { var count: Int { get } } func count(countable: some Countable) { print(countable.count) }

-