-

Audio Workgroupsの紹介

オーディオ AppまたはプラグインのApple Silicon Mac用の微調整: Audio Workgroupsを使用してリアルタイムスレッドを登録し、Appに歌わせる方法を説明します。System on a Chip(SoC)の電力効率、および、Appとプラグインの速度と音声を改善するために新しいAPI を利用する方法について、さらに詳しく学びます。

リソース

-

このビデオを検索

Hello, and welcome to WWDC.

Hello. I'm Doug Wyatt from the Core Audio team, and today I'd like to introduce you to audio workgroups. If you develop an audio application or plug-in that creates realtime threads, then this talk is for you. You're probably using realtime threads for very low-latency audio synthesis or signal processing.

It's important that you adopt new API audio workgroups. And these new APIs are available in the fall 2020 releases of macOS and iOS.

Now, if you're wondering if you should create your own realtime threads, the answer is probably no. If you do go down this path, though, then follow the first rule of performance tuning: measure everything.

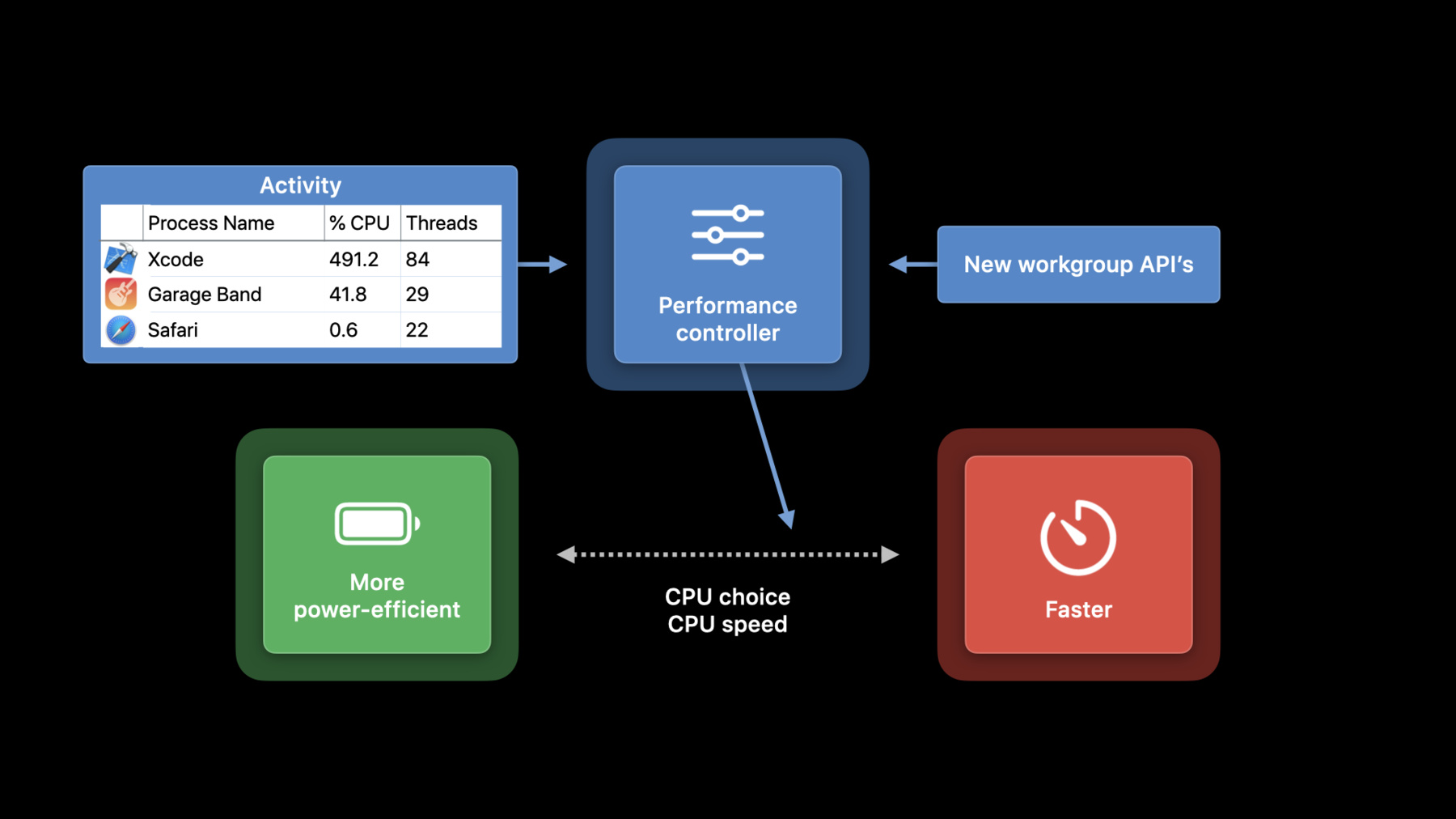

Okay, let's dive in with some background. Modern CPUs have performance controllers, which make trade-offs between power consumption and computing power.

The performance controller helps assign threads to CPUs. The CPUs themselves may have differing power and speed characteristics. The performance controller can also dynamically change the clock frequency of the CPUs.

Up until now, the main input into the performance controller's decision-making has been observations about the running applications and daemons: how many threads are they using and how much work they are doing? Now, because of the time-critical nature of audio, we've given it a new input into the performance controller: the new workgroup APIs.

Let's look now at audio workgroups. Later, we'll see how to use them in your apps and Audio Unit plug-ins.

First, a workgroup consists of one or more threads. There is a master thread which wakes up periodically.

It tells the kernel when it begins a work cycle, and what the deadline for that work is.

The master thread might signal and wait for other threads that are part of the workgroup and those threads might be in other processes.

At the end of each work cycle, the workgroup, again, notifies the kernel.

This diagram illustrates how Core Audio runs an I/O thread in the audio server. This thread wakes up at regular intervals and has a deadline for each cycle.

Each time it wakes up, it calls the client to produce output. When the client is done, then the output data is written to the hardware and the I/O thread sleeps. This is the master thread of a device workgroup. It informs the kernel of the beginning and end of each work cycle.

If the client takes too long to produce output data, then the thread misses its deadline and we get an overload. The user hears this as a discontinuity, or a glitch, in the audio.

So, it's important that the performance controller be aware of the threads that are producing audio with that deadline. For every audio server I/O thread, there is a second thread in the client application. We see here that the audio server wakes and waits for this thread on each I/O cycle.

Both threads are colored in green here. This illustrates that the audio frameworks join the client-side thread to the device's workgroup. So, the kernel knows that both threads are working together towards a common deadline. Here's a more complex situation: the app is hosting two Audio Units which are running in other processes. In each render cycle, the app renders the two Audio Units serially, using two inter-process calls.

Here too, all of the realtime rendering threads are owned by the audio frameworks, so they are colored in green to indicate that they are all part of the device's workgroup. What we've just seen is the good news. The audio system's realtime threads are automatically joined to workgroups. Now, let's look at apps which have their own realtime audio threads. Here we have an app that's running two auxiliary threads in parallel with the I/O thread. For example, it might be rendering three complex tracks. It splits the work between the auxiliary threads and the I/O thread, and the I/O thread waits for the worker threads and mixes the final result. These threads are in shown in gray to illustrate a problem: they're not part of the workgroup.

They're running with the same deadline as the threads in the workgroup, but the scheduler doesn't know this. So, the solution is to join these threads to the workgroup. And we can see how.

First, obtain the device's os_workgroup object. On macOS, you can obtain it directly from the audio device with the HAL API.

On any platform, you can obtain it from the input/output audio unit, AUHAL, or AURemoteIO, using these properties. Once you've obtained the device's workgroup, then in your realtime thread, call os_workgroup_join. This joins the thread to the workgroup and only has to be done once.

You'll also need to call os_workgroup_leave before your thread ends. The details are in these header files.

After you've done this, then your app's parallel realtime threads are part of the device's workgroup. All the threads are in green.

Let's look at a more complex app. It is also running two auxiliary threads, but they are running asynchronously to the I/O threads, with different deadlines.

Since they have different deadlines from the device I/O threads, these auxiliary threads need to be in two additional workgroups. Let's see how. First, instead of obtaining the device's workgroup as we saw before, create your own workgroup using AudioWorkIntervalCreate.

As before, you need to join the realtime threads to the workgroup, using os_workgroup_join. And again, this only has to be done once.

You might have multiple threads in your group, but one is controlling the others. It's the "master." In this thread, on each work cycle, call os_workgroup_interval_start. The startTime parameter can be "now," as reported by mach_absolute_time. Or it can be in the past, if you know exactly when your work cycle was scheduled to start, presumably in the recent past.

The deadline has to be greater than the start time.

The units are mach_absolute_time. Here, be sure not to assume that mach_absolute_time are nanoseconds or anything else. Be sure to use mach_timebase_info to get the clock frequency of mach_absolute_time.

Then at the end of each work cycle, call os_workgroup_interval_finish.

After you have joined your asynchronous auxiliary threads to workgroups, things look like this. There are three independent workgroups working on separate cadences with separate deadlines that cover apps which create realtime threads. Now, let's look at Audio Units which create realtime threads.

The vast majority of Audio Units don't do this, but there are a few large and powerful ones that do create their own extra rendering threads. Here's an example. This Audio Unit is dividing its work between four threads, three that it has created, plus one from the host.

You can see the problem here: the Audio Unit has realtime threads that are not part of a workgroup. It's being called by the host in some unknown thread context. That context could be the device's I/O thread, or it could be a non-realtime worker thread. The Audio Unit doesn't know. To solve this, we're introducing the AURenderContextObserver. This is a block in the audio unit that gets called before each render request. As the audio unit developer, you implement this render context observer property to return a block that receives a context struct. This struct contains an os_workgroup.

So, at render time, when you see that the context's workgroup has changed, you can join your auxiliary realtime threads to that workgroup, as we saw earlier, using os_workgroup_join.

It's important to be aware here that the workgroup may change from one render call to the next.

After you implement the render context observer, and you join your realtime threads to the workgroup it observes, then here too we have all realtime threads joined to workgroups. It's very important to note here: the system informs Audio Units of the workgroup using the render context observer. This happens automatically when the host renders. So, the host should not try to call the render context observer. Again, the system handles this automatically. That brings me to the main point of this talk: all audio threads should be joined to workgroups. And now we've seen the APIs you can use to do this. You might be wondering about non-realtime audio rendering threads. They don't have deadlines, so they can't be joined to workgroups. If your non-realtime threads do have deadlines, that might be a reason to convert them to realtime. But again, measure performance if you start down this path.

If you're creating parallel worker threads, there is a new API which will recommend how many threads to create: and that's os_workgroup_max_parallel_threads.

You can't call this until you know your workgroup, which, if you're an Audio Unit, might not be until you're rendering in realtime.

In that case, when your Audio Unit is initialized, then you create as many threads as there are CPU cores, but make a render-time decision to use only the recommended number of threads.

To summarize, here are all the different kinds of realtime threads we looked at, and how to make sure they are joined to workgroups. The system frameworks take care of all the threads they manage.

For app threads that are parallel to the device thread, join them to the device's workgroup.

For app threads that are asynchronous to the device thread, create and manage a workgroup of your own and join those threads to that workgroup.

For Audio Unit threads that are parallel to the host's render requests, implement a render context observer, and join threads to the workgroup it observes.

We've seen how to improve the performance of your app or plug-in's audio realtime threads by joining them to audio workgroups. Thank you for your time and attention, and I look forward to seeing your great music and audio apps.

-